The Burnt Island Lighthouse

by: Mary Alice Snetsinger

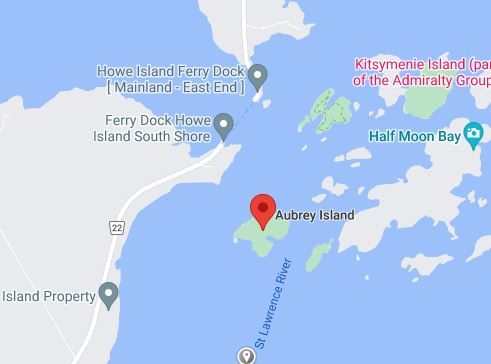

Every one of these small lighthouses built along the Canadian side of the River seems to have some unique aspect. While sparse on images and information, and never one of the “popular” lighthouses, Burnt Island saw two women appointed as lightkeepers, including the first woman officially recognized as a lightkeeper anywhere in the Thousand Islands. It was the last completed, and the most westerly of nine lighthouses built in 1856 on the Canadian side of the border. It was located at the east end of Burnt Island (today, it’s more commonly known as Aubrey Island, and is part of Thousand Islands National Park).

This article refers to Burnt Island Lighthouse throughout, although the name of the island has been far less consistent. According to Susan Weston Smith’s book, The First Summer People, this island has been known by more official names than most in the Thousand Islands. William Fitzwilliam Owen, famous for his survey work on the Canadian Great Lakes, named it The Porter. Unwin’s 1874 survey lists it as “Burnt, Bear, Smoke, Dark or Porter Island.” In addition, Smith notes that it was also registered as Marvin (sic) Island, after the first lightkeeper. In 1904, the island became part of the Canadian park island reserve (in what would become Thousand Islands National Park), abruptly titled Aubrey. Regardless of its new name, the lighthouse had been on the island for half a century by this point, and it continued to be called the Burnt Island Light.

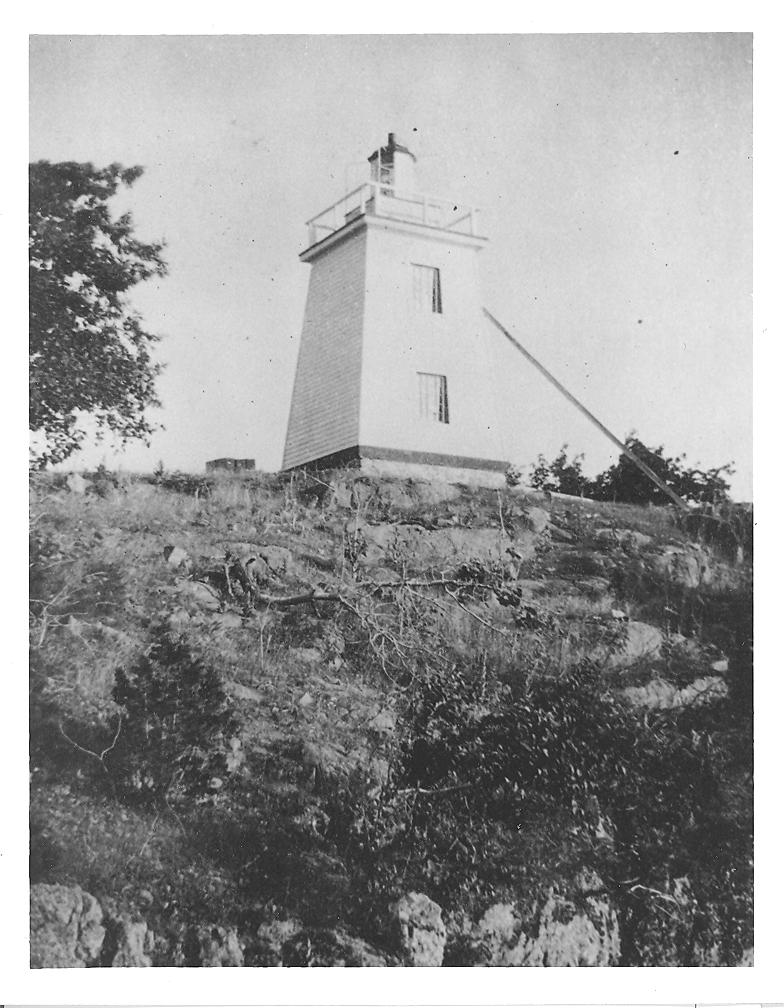

Images are sparse, but the James Esson collection at the National Archives of Canada contains a distant shot. A detail of the photo (dating between 1875 and 1885) shows a small, square white wooden tower, topped by a lantern – essentially identical to the other eight lighthouses lighted along the river in 1856.

The first lightkeeper appointed to Burnt Island lighthouse was Joseph Mervin, who acted for over twenty years. In the 1878 Sessional Papers, the report to the LightHouse Board states:

“Visited and supplied this Station on 7th July [1877]. It is a white square wooden tower, 26 feet high, and stands on the SE part of the Island; has an iron lantern; 3 feet 4 inches in diameter; containing two No. 1 flat-wick lamps, with two 14-inch reflectors, and is a fixed white catoptric light; can be seen six miles; size of glass, 14 x 13 inches.

Cistern required to be repaired and plastered; the tower requires repainting. The dwelling-house [land for which was not purchased until 1859, 1861] requires ceiling with wood and painting.

The Keeper of the Station is Mr. Joseph Marvin (sic), 79 years of age, whose family consist of seven.

We found the light well kept, and in good order.”

When Joseph Mervin died the following year, his wife, the semi-anonymous “Widow of J. Mervin,” was left in charge of the lighthouse. She was paid $10.41 for “taking charge of the Light,” from 1st to 15th April 1878. While it was for a short period only, Mrs. Mervin thus became the first woman officially recognized as a lightkeeper in the Thousand Islands, on either side of the border.

Mrs. Mervin would not be the last woman to act as lightkeeper at Burnt Island. The light was initially powered by sperm whale oil, but this was soon replaced by coal oil in 1860. Coal oil would be a staple illuminant for many years, but in the early 1900s, acetylene was being tested. In 1904, all the Canadian lighthouses along the river were converted to acetylene, making them “practically automatic.” As a result, many of the lightkeepers were dismissed, including then-acting James Acton.

Instead, Manley Cross became the keeper of six lighthouses along the river, including Burnt Island. Under his watch, in 1906, the old wooden light tower was replaced by a “white cylindrical steel gas holder, surmounted by [a] red pyramidal steel frame supporting a lantern.” After Manley Cross’s death in 1907, his surviving spouse Jennett Cross, became the second woman to be appointed at Burnt Island.

Coincident with the establishment of the gas beacon in 1906, the Lists of Lights describe the lighthouse as “unwatched,” at apparent odds with the Sessional Papers, which list first Manley then Mrs. Manley (Jennett) Cross as lightkeepers.

Given the degree to which these lights were automatic, one lightkeeper was assigned to effectively act as a caretaker for the six widely spread lights (Burnt Island to Gananoque Narrows, along some 9.35 km or 5.8 miles of the river). The List of Lights for 1909 and 1910 specifically remark that the gas buoys are unwatched, and “their lights cannot therefore be depended upon in the same way as those shown from watched lighthouses.” It makes sense that a light with only a caretaker would have far less human presence than one with a resident lightkeeper.

James Acton regained his job in 1912 when, “for reasons best known to themselves,” the government reverted to coal oil, and former keepers were recalled to their positions. Jennett Cross continued on at Gananoque Narrows and Jackstraw Shoal lighthouses.

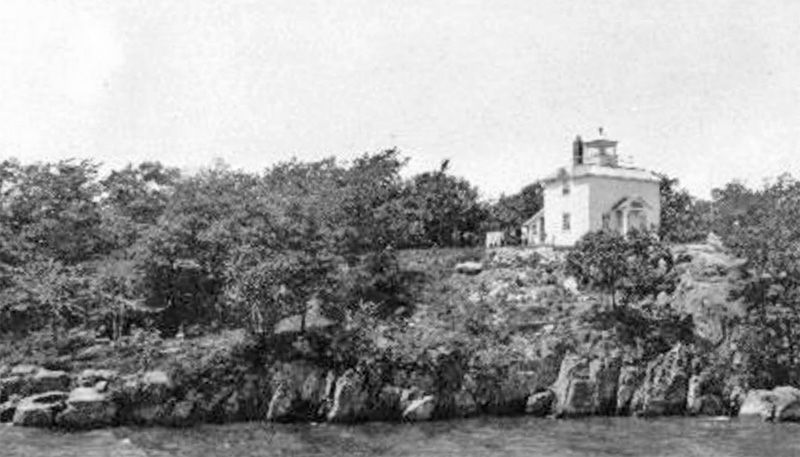

Fire was and is an ongoing issue in the Thousand Islands (see Lynn McElfresh’s article from May 2012 and Glenn Sandiford's article from May 2022.). Huge fires grabbed headlines (e.g., the extensive fire at Thousand Island Park in 1912, which saw the loss of The Columbian Hotel, some 200 cottages, and more), but smaller fires wreaked their own share of destruction. The lightkeeper’s dwelling on Burnt Island was not built for several years after the construction of the lighthouse, and later featured as “in bad repair” in reports of the lighthouse inspector. In 1916, however, the keeper’s house on Burnt Island was destroyed by fire, so a new combined dwelling and light tower was constructed.

In 1916, a Notice to Mariners from the Lake Carriers Association announced the new lighthouse on Burnt Island:

“The fixed white light on the eastern end of Burnt Island has been established in a new structure erected on the site of the gas beacon, which has been removed. The light is exhibited, 64 feet above the water, from a square lantern on the middle of the roof of a rectangular wooden dwelling painted white.”

As the century proceeded, technological advancements led to several further alterations. 1945 saw a conversion to electric power, and mariners looked for a “white wooden tower with [a] daymark.” After Thomas Ferris retired in 1947, and with the lighthouse converted to electric power, a keeper was deemed no longer necessary, and it became an unwatched lighthouse. Changes in 1984 resulted in a “white square skeleton tower, fluorescent orange rectangular daymark.” Sometime between 2006 and 2009, it changed yet again, to a “white cylindrical mast, orange upper portion; seasonal,” the description that still applies in 2022.

By Mary Alice Snetsinger, ecoserv@kos.net

Mary Alice Snetsinger grew up in the United States and Canada and worked for four years at Thousand Islands National Park. She became interested in the 19th century lighthouses of the Thousand Islands in 1997 and has been researching them ever since. Mary Alice provided TI Life with articles about Wolfe Island’s Lighthouses, Fiddler's Elbow, Lindoe Island Light, the Ogdensburg Harbor Light and Cape Vincent Harbor Lighthouses; click here to see these articles and here to see the latest , Spectacle Shoal light, Sisters Islands Lighthouse, Sunken Rock Light, Crossover Lighthouse and Rock Island Lighthouse, Part I and Part II .