Rock Island is probably the best documented lighthouse in the Thousand Islands, certainly on the American side of the border, and one of its lightkeepers was a famous (or infamous, depending upon your point of view) character, known as the Pirate of the Thousand Islands. Like both Crossover Island and Sunken Rock lighthouses, it was lighted in 1848. Its location along the main shipping channel, between Fishers Landing and Thousand Island Park on Wellesley Island made it highly visible to area residents and tourists. Engravings, paintings, real photo postcards, photographs, snapshots, and modern photographs abound. Further cementing its preservation, it is today protected within Rock Island Lighthouse State Park.

The best known image of the first lighthouse comes to us courtesy of Benson Lossing, who visited the lighthouse and interviewed Bill Johnston, then lightkeeper, in 1860. He published the image in 1868, its lightkeeper standing on the front porch, in his Pictorial Field Book of the War of 1812. As the original lighthouse at Crossover Island was identical, we have a clear understanding of what that lighthouse looked like as well.

Like those at both Sunken Rock and Crossover Island lightstations, the original structure did not age well. Only 25 years after the original construction, the Light House Board report of 1873 stated:

The tower and dwelling are in a similar condition to that of [the identical] Cross-over Island. A new tower is imperatively necessary. The dwelling might be repaired, but it is not considered economical in the end to do so, as it would only be postponing the building of a new one [in] a few years, and it would probably cost less to build tower and dwelling together now. An appropriation of $14,000 is required for a new tower and dwelling.

The recommendation was reiterated every year following. In 1880:

"The buildings are very old, and at no distant day must be rebuilt. The dwelling and out-buildings were painted. A new roof was put over the oil-room and a new floor laid in it, and the walls lathed and plastered, and the station put in as thorough repair as it was capable of. A new lantern must be put on the tower, which will cost $1,456.40."

Finally, in 1882, some funds were dispersed for the lighthouses in the Thousand Islands. At each of Rock Island, Sunken Rock, and Crossover Island, new and virtually identical iron towers were built.

A new iron tower was erected to take the place of the low wooden lantern on the top of the keeper’s dwelling. The tower rests on a floor of concrete placed on the dressed surface of a rock of the island. The tower was lined with brick to the first landing; above that with wood. Lockers were built for the lamps, &c., in the tower. Repairs should be made to the landing and walks, at an estimated cost of $300. A suitable buoy-house should be placed on this island, at an estimated cost of $1,500; also, the keeper’s dwelling should be rebuilt, at an estimated cost of $4,000.

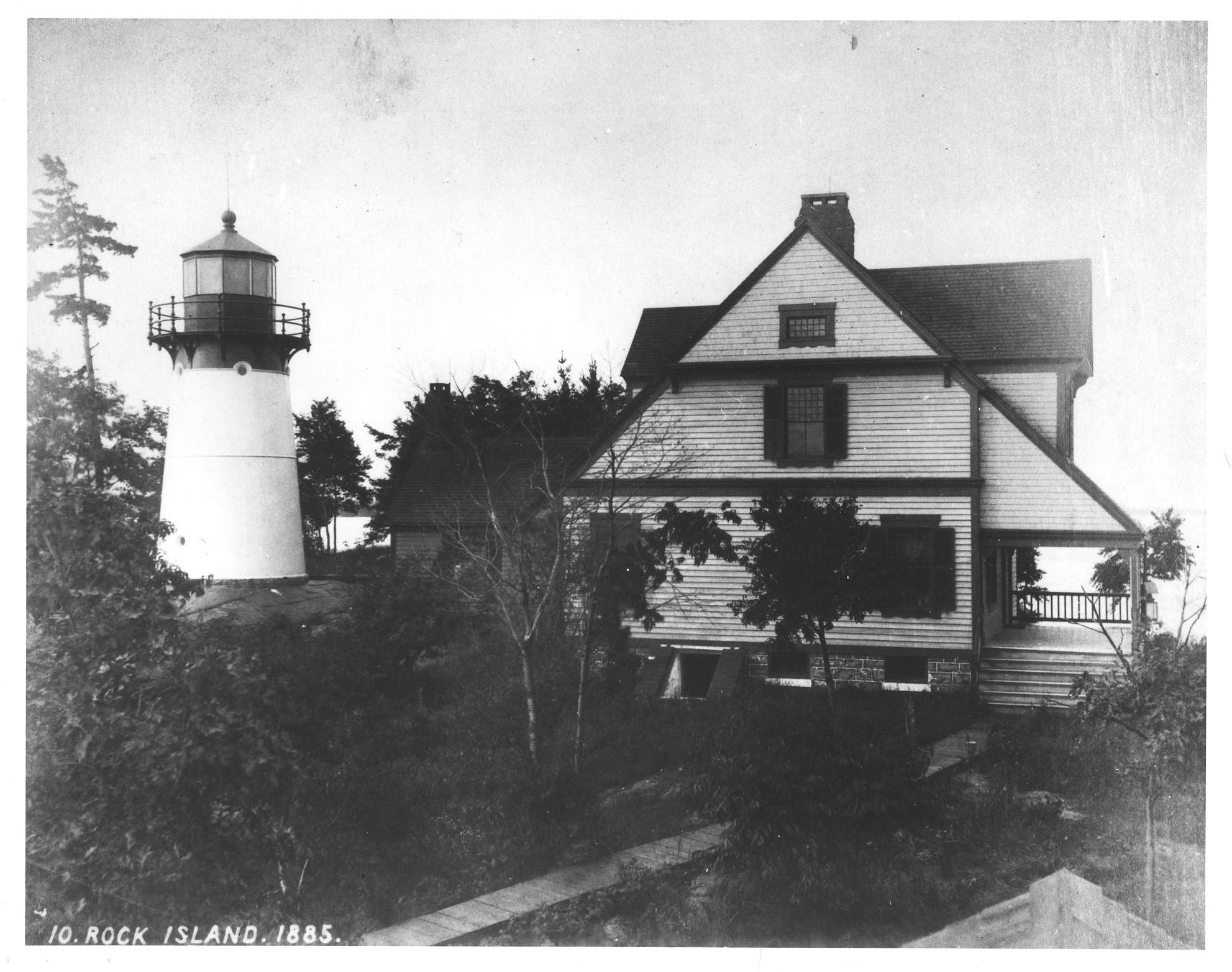

In 1883, work on the walkways and boat-landing was completed, and the following year the lightkeeper’s house was rebuilt. The 1885 report of the Light House Board reported the completion of that work, as well as the sinking of a well. Wells were also completed at Crossover Island, Sister Island, Ogdensburg, and Sackets Harbor in the summer of 1884. If you examine the National Archives photograph from 1885, you can see the white signal lantern that was hung from the veranda of the dwelling, in the direction of the Thousand Island Park dock. This lantern was used during the hotel season because the lights from the tower were obscured by the roof of the keeper’s dwelling, in the direction of Thousand Island Park.

Over the following decade there were several improvements made to the light station and grounds: in 1890, 270 cubic yards of earth were imported, and the bare rock was covered with fertile soil to “improve the appearance of the station;” in 1891, the west stoop of the dwelling was permanently closed in for better protection against the cold; and in 1895, the tower was “raised bodily 5 feet, and under it was built a solid octagonal wall of red granite laid in Portland cement mortar,” which allowed discontinuation of the white signal lantern on the veranda.

This 1894 photograph, published in John Haddock’s 1895 book, The Picturesque St. Lawrence River, shows some of the alterations. Though photographed from a different point of view, the base of the tower clearly rests close to the native stone, as in the earlier image, so the tower had not yet been raised. You can get some idea of the change to the grounds that resulted from importing fill to smooth and level the grounds. The man standing in the entrance to the lighthouse is then-keeper Michael Diepolder. Notice the brown color of the tower here (as opposed to white in 1885). This color was changed back to white in 1899 for improved visibility.

That there had been long-standing concerns about the position and effectiveness of the lighthouse on Rock Island, is demonstrated by the incremental adjustments that were made at this light station. Resolving the problem once and for all, in 1903:

The light tower was moved about 180 feet to the water’s edge and set upon a brick substructure, 20 feet high, with a concrete base. The height of the focal plane was thus increased from 45 to 50 feet. There was a temporary light shown from a lens-lantern from the opening of navigation on March 30 to April 30, 1903, when the regular light was established in the new tower. A masonry causeway about 70 feet long was built and provided with a cement walk and a hand railing. Some 609 square feet of cement walk including that on causeway was laid and 185 square feet of plank walk have been built.

From this point to the present, the general appearance of the lighthouse has not changed substantially, and many photographs and sketches can be found. It remains much the same today, and visitors to the island can climb up inside the lighthouse tower to get a spectacular view from the lantern room.

Lightkeepers

The island saw numerous keepers come and go during almost one century of lightkeeping history. Because Rock Island is so well known, and preserved as a state park, more research effort has gone into these individuals, and can often be found online.

Lightkeepers of Rock Island Lighthouse

• Chesterfield Parsons 1848 – 1849 Resigned.

• John Collins 1849 – 1853 Resigned.

• William Johnston 1853 – 1861 Removed.

• Samuel Spaulding 1861 – 1865 Resigned.

• Joseph Collins 1865 – 1870 (son of John Collins) Removed.

• Willard Cook 1870 – 1879 Removed.

• Foster Drake 1879 – 1886 Removed.

• Michael Diepolder 1886 – 1901 Died.

• Emma Diepolder 1901 – 1901 Resigned.

• Eugene Butler 1901 – 1912 Resigned.

• John Belden 1912 – 1940 Retired.

• Frank Ward 1940 – 1952 Transferred from Crossover Island.

Lastkeepers

• John Van Ingen 1952 – 1955 USCG – dates unsure. Retired.

• Dennis Carroll 1955 – 1956 USCG – dates unsure.

• John Trucker 1956 - 1956 USCG – dates unsure.

Rock Island (along with Sunken Rock and Crossover Island) was purchased from Chesterfield and Mary Ann Pearsons and Azariah and Mary Walton. In 1848, Chesterfield Pearson was appointed the first lightkeeper of the Rock Island Lighthouse, acting for a little over one year. His replacement was John Collins, who acted until his own resignation in 1853. (In keeping with lighthouse keeping often running in families, John Collins’ son Joseph would become the fifth lightkeeper on the island, a dozen years after his father’s resignation.)

John Collins would be followed by the best known of the lightkeepers: Bill Johnston, the Pirate of the Thousand Islands. William (or Bill) Johnston (AKA Pirate Bill Johnston) has a storied history in the Thousand Islands. Johnston was certainly a larger-than-life figure, much admired and equally despised in his day. (See Rock Island Lighthouse Part II, March 2022)

Emma Diepolder served as the ninth lightkeeper at Rock Island following the death of her husband, Michael Diepolder. She was not the first woman appointed as a lightkeeper in the Thousand Islands – that distinction goes to the “widow of J. Mervin” at Burnt Island lighthouse (Admiralty Islands) in April 1878. Nor was she the longest serving – that honour goes to Jennett Cross (widow of Manley Cross), who was keeper of Gananoque Narrows and Jackstraw Shoal lighthouses for close to six years (1908 – 1913). But Emma Diepolder was the only woman to be officially appointed to one of the American lighthouses in the Thousand Islands. On both sides of the border, women who were considered to be experienced keepers by virtue of having been married to a lightkeeper could be appointed as the official keeper following the death of a husband. Michael Diepolder died suddenly and unexpectedly on July 16, 1901, and Emma carried out the lightkeeping duties (at the same annual salary of $560) until Eugene Butler was appointed on October 1, 1901.

Frank Ward transferred to Rock Island from Crossover Island in 1940, to become the last of the lightkeepers. The lighthouse was electrified in 1939. While there, he was formally enlisted into the U.S. Coast Guard service, which was shortly to replace the Lighthouse Service in managing the lighthouses. In 1952 he left Rock Island, and the keepers who followed him were caretaker members of the Coast Guard who did not live on the island.

Further changes followed: in 1958 it was no longer listed as an active lighthouse; in 1976 it was declared surplus; in 1978 it was added to the Register of Historic Places; in 1988 converted to solar power; and in 2013, the lighthouse was opened as Rock Island State Park. The island is accessible by boat, and is open to the public, with docks and a visitor’s center.

*Part II, Volume 17, Issue 3, March 2022. This next article will provide more information about the infamous Pirate Bill Johnston!

By Mary Alice Snetsinger

More about Mary Alice Snetsinger, ecoserv@kos.net

Mary Alice Snetsinger grew up in the United States and Canada, and worked for four years at Thousand Islands National Park. She became interested in the 19th century lighthouses of the Thousand Islands in 1997 and has been researching them ever since. Mary Alice provided TI Life with articles about Wolfe Island’s Lighthouses, Fiddler's Elbow, Lindoe Island Light, the Ogdensburg Harbor Light and Cape Vincent Harbor Lighthouses; click here to see these articles and here to see the latest four, Spectacle Shoal light, Sisters Islands Lighthouse, Sunken Rock Light and Crossover Lighthouse.

Editor's Note: Our thanks to Mary Alice who never ceases to find interesting and unknown facts about these iconic lighthouses of the Thousand Islands! We are honored to share this information to TI Life readers. She says there are only a few more to go! Then what?

Editor's Note: Mark A Wentling's contributed one of our first articles after I became the editor in November 2008. His "Rock Island Lighthouse: A Story of Discovery" is still available on TI Life. Mark also maintains a website "The Keepers" with biographies of Rock Island Lightkeepers.

Posted in: Volume 17, Issue 2, February 2022, History, People, Places

Please click here if you are unable to post your comment.