Rock Island Lighthouse, Part II

by: Mary Alice Snetsinger

[See Rock Island Lighthouse, Part I]

William (Bill) Johnston has a storied history in the Thousand Islands, and it is sometimes difficult to separate the man from the legend – or from the mythologized “pirate” celebrated at the annual Alexandria Bay “Bill Johnston Pirate Days” festival.

Bill Johnston was born in 1782 in Trois-Rivières in Lower Canada (Québec). His parents were United Empire Loyalists (his father was Irish and his mother was American), who had fled the United States during the American Revolution. He married an American, farmed, then eventually purchased a Kingston grocery store. At age 30, he was a prospering merchant. But things changed dramatically after the United States declared war on Great Britain in 1812, and began attacking her colonies in Canada. Bill Johnston was accused of spying for the Americans, and his property was seized. While Johnston escaped to Sackets Harbor with his family, this led to his thirst for revenge. Bill spent the war years (1812-1815) spying on the British, attacking supply boats, etc., and participated in the battles at both Sackets Harbor and Chrysler’s Farm.

Johnston’s biggest claim to fame, however, and the source of his “pirate” moniker, was the result of events years later, in May of 1838. Benson Lossing interviewed Johnson during visits to Clayton and the Thousand Islands in 1858 and 1860, and published a detailed account in his 1868 book, the Pictorial Field Book of the War of 1812. The “Patriot Wars”, as the insurrectionist efforts of 1837 and 1838 were known, was a period of renewed tension between the two countries, with an element of the Canadian population chaffing against the strictures of British rule and pushing for self-determination. This was greeted eagerly by a number of American “patriots” who were eager to free Canada from the perceived “yoke of British rule,” and Bill Johnston was readily persuaded to join the effort.

It should be understood that these efforts were not sanctioned by the government of the United States. In May 1838, Johnston led a small group of thirteen men in seizing the British steamer Sir Robert Peel. When promised reinforcements (of 200 men) from the American side failed to materialize, and unable to handle the steamer with the number of men he commanded, he burned the ship. “Remember the Caroline!” he reportedly shouted, in reference to an American ship destroyed by the British at the end of the previous year. A price was put on his head, and he was hunted by both British and American authorities. Franklin B. Hough’s (1888) account of events is much the same.

In November of the same year, the Battle of the Windmill ensued at Prescott, centered around the windmill that would later become Windmill Point Lighthouse. The extent of Bill Johnston’s involvement is murky, but according to the account he rendered to Benson Lossing, he joined in the “expedition to Prescott” to “keep out of the way of both parties” (that is, the British and the American authorities). He was involved in ferrying supplies to Prescott on the first day of the battle and helped to free two rebel schooners that had grounded. He was seen publicly in the streets of Ogdensburg in the days after the battle but was not arrested. A few days later, he finally surrendered to authorities of the United States. After an almost comedic series of arrests, trials, an acquittal, a conviction, and jail escapes, he sought a pardon from the President, a request that was first refused by President Van Buren, but then granted to him ten days later by President Harrison (the second of three Presidents to serve the US in 1841).

Bill Johnston was certainly a larger-than-life figure, much admired and equally despised in his day, and he was apparently very fond of recounting his own legend in his later years. Several articles about him have been published in Thousand Islands Life. It is one of the ironies of his life that only a few years after the American government had set a price of $500 as a reward for his capture, they began to pay him $350 annually as the third lightkeeper at Rock Island.

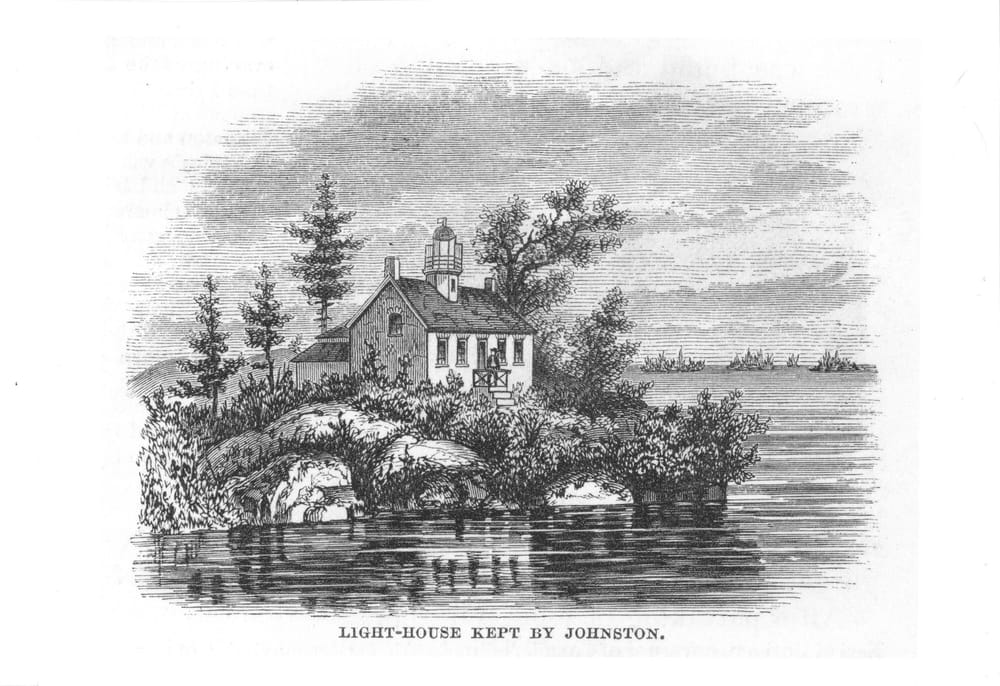

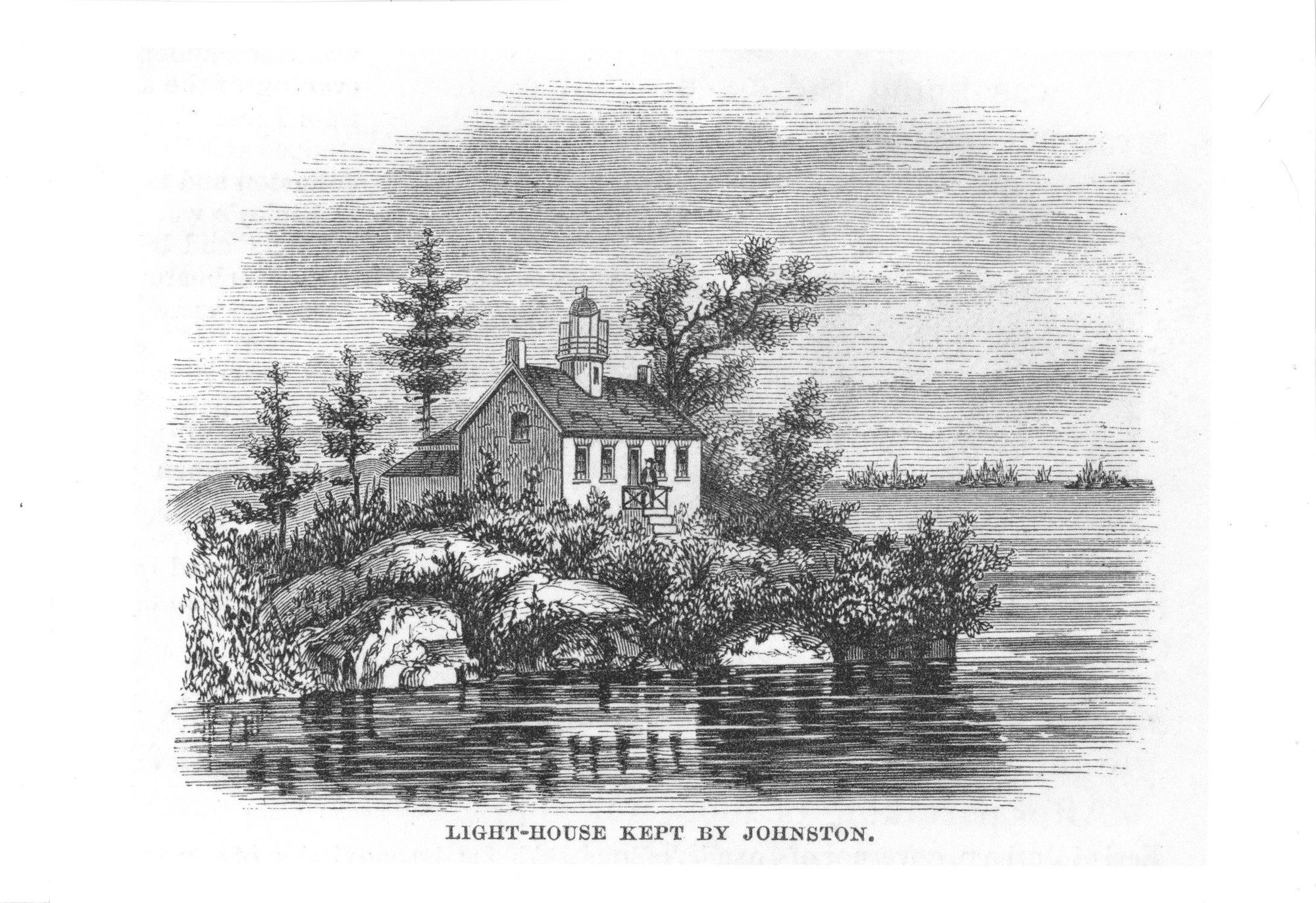

It is thanks to his notoriety that Benson Lossing visited and interviewed that “hero of many a romantic legend,” providing us with one of the few known images of the first lighthouse on the island, but also with a depiction of its third lightkeeper.

Bill Johnston’s years as lightkeeper (1853 – 1861) were certainly more staid, as perhaps befitted an aging pirate; he was 71 years old at the time that he was appointed (although Lossing described him in 1860, then 78 years old, as a “man of medium size, compactly built, and full of pluck”).

Unfortunately, records for the American lighthouses were sparse in their early days. In 1852, a comprehensive report to the Light-house Board initiated the move toward a more professional organization, signaling that the days of political appointments were coming to a close, but records remained thin and change was slow to come. Almost every aspect of lightkeeping in the United States was found wanting in the 1852 report (including materials, locations, lighting apparatus, lightkeeping standards, maintenance, and oversight), but the great economy and efficiency of the lens or Fresnel light, as contrasted with the reflector lights, was highlighted. During Bill Johnston’s tenure (in 1855) the lantern at Rock Island was refitted and equipped with a sixth order Fresnel lens.

In 1861, however, Johnston lost his position as lightkeeper with a change in the political climate in Washington; Abraham Lincoln took office in March, and Johnston was “removed” the following month. Bill Johnston retired to live in Clayton, where he set up residence at Walton House, then owned and run as a hotel by his son (Stephen) and daughter-in-law (Maria) Johnston. He died in 1870, shortly after his 88th birthday.

By Mary Alice Snetsinger, ecoserv@kos.net

Mary Alice Snetsinger grew up in the United States and Canada and worked for four years at Thousand Islands National Park. She became interested in the 19th century lighthouses of the Thousand Islands in 1997 and has been researching them ever since. Mary Alice provided TI Life with articles about Wolfe Island’s Lighthouses, Fiddler's Elbow, Lindoe Island Light, the Ogdensburg Harbor Light and Cape Vincent Harbor Lighthouses; click here to see these articles and here to see the latest four, Spectacle Shoal light, Sisters Islands Lighthouse, Sunken Rock Light, Crossover Lighthouse and Rock Island Lighthouse, Part I.

Editor's note: See Mark A Wentling's website for more details about this important Thousand Islands history.