Out of a Flood: The Upper Canada Migratory Bird Sanctuary

by: Craig I. Stevenson

My first memories are of the geese, of flocks of Canadas descending to cobs of corn tossed from behind a tractor while crowds gather to watch the noisy spectacle. It’s sometime around 1980, and I’ve half-climbed a split-rail fence to watch the arriving birds push and nip and gobble at cobs—a noisy affair, full of hissing and urgent honking and squalling grunts, all punctuated by air thrust through flight pinions as late-arriving waves join the fray, timed for birds and visitors alike at half past two in the afternoon. These are the dull days of late October, the peak of goose migration in eastern Ontario.

I am too young to know that it has not always been this way.

The Before

The Upper Canada Migratory Bird Sanctuary is an oddity of history, its nine thousand hectares of field, wetland, and uplands established on land reclaimed through unique circumstances. There are layers of the past here, fading remnants of a place that lived a very different life before its dedication to wildlife habitat.

Officially opened in 1961, the sanctuary is a collection of many stories—stories that remain evident in the sight of crumbling roadways and scattered foundation stones slowly receding into a naturalized environment.

Today, few people remember its prior life as a series of communities, a life ended in 1958 with the flooding of the St. Lawrence Seaway and Power Project. It remains as much a lesson in history as a still-developing conservation project.

The Concept

Looking beyond the shoreline at the south edge of the sanctuary, it is difficult to imagine a waterfront comprised of maritime towns and canals. When the waters were raised on July 1, 1958, a new landscape emerged. What remained from before were memories and, in periods of low water, scattered physical reminders of the past.

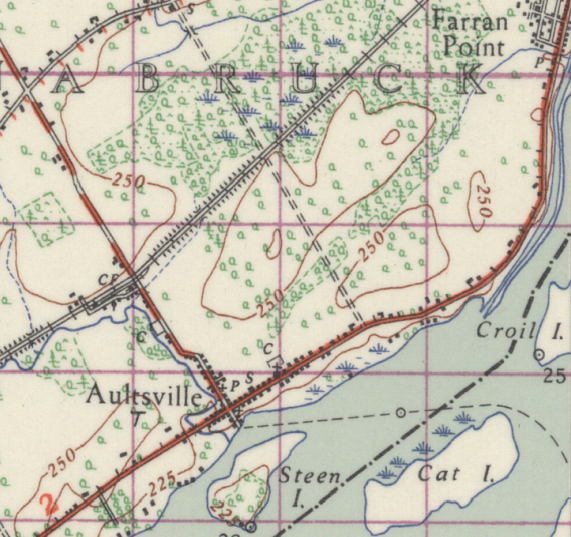

The streets and foundations of a destroyed town mark the sanctuary’s upriver edge. Aultsville, Ontario was a town whose maritime character was shaped by its position along the river. By the time of its demise, Aultsville had already seen distinct phases of river life pass on. In the nineteenth century it served as a stop-over for timber rafts floated downriver from Kingston, the point where pilots familiar with fast water embarked to guide the rafts through the downstream Long Sault Rapids. Until the Second World War it was served by steamship commerce at the town’s government wharf. Arthur Dafoe, a local merchant, emerged as a prominent decoy carver along the St. Lawrence, and his hardwood blocks are now assigned collector’s value. Locally, it remains memorable that Aultsville’s fate during the Seaway construction was to have several of its fine old houses burned experimentally by the Canadian government’s National Research Council to further knowledge of fire-proof house design.

At the eastern edge of the sanctuary are the remnants of another village, Farran’s Point, where a set of waterfront locks lifted up-bound ships into a canal bypassing fast water and rapids. After the flooding, house foundations remained visible above the surface. The heavy block stonework of its canals and locks are fully intact in the depths just offshore.

Other subtle signs of the sanctuary’s prior existence are found back from the river’s edge.

The arrow-straight road into the sanctuary—and the cycling trail that follows from the road after it veers toward the visitor’s center—sit atop the former rail bed of the Canadian National Railway. The rail line was also, out of necessity, moved out of the way of the Seaway’s impending flooding.

Nowhere is the sanctuary’s past overtly obvious—and yet it is everywhere.

Lake St. Lawrence

When the waters rose, a new river was created. Now named officially as “Lake St. Lawrence”, the altered waterway was designed to rise and fall in level as needed to accommodate commercial navigation and hydroelectric production. Residential habitation along the River was deemed incompatible with these needs. The shoreline remained vacant and under the control of a variety of federal and provincial authorities, with the purpose of creating a series of parks and attractions to stimulate the local tourist economy.

The idea for a dedicated bird sanctuary was proposed by Ontario’s Department of Lands and Forests in 1954. Like the Seaway project, it was a product of its time. This was a conscious act of creation, intended to show that a specific section of land and water could be re-invented as habitat—just as the St. Lawrence could be re-purposed as a global shipping route and a source of hydroelectricity.

The sanctuary’s first act, in 1959, was to establish a group of geese trapped from Chesapeake Bay as an initial resident population. Those birds, combined with a feeding program, quickly attracted migrant geese to the sanctuary’s central pond and grassy plain. Fred Bodsworth, a prominent ornithologist of the day, predicted that the annual gathering of geese would propel the Upper Canada Migratory Bird Sanctuary to a level of tourist interest on par with the renowned Jack Miner Sanctuary in southern Ontario.

That was a bold prediction, and characteristic of the glossy enthusiasm of the age for all things that seemed to signal human progress. In that spirit, we can forgive him for failing to mention the riverside destruction that preceded the sanctuary’s creation.

The Sanctuary

What started as a project to attract Canada geese and a seasonal crowd of observers has since taken on a broader conservation-minded character.

In the 1970s, Ontario’s Ministry of Natural Resources built a waterfowl banding trap at the sanctuary’s central pond. A Lake St. Lawrence Master Plan positioned the sanctuary as a core conservation area within a broader controlled hunting zone, with the sanctuary flanked by a series of designated hunting blinds that continue to provide excellent autumn waterfowling opportunities.

In 1979, Ducks Unlimited Canada established a project on a strip of water that frames the sanctuary’s northern edge. Using the former Canadian National railbed as a barrier, and with the establishment of a control gate along the rail bed’s wall, the project created a stretch of wetland habitat unaffected by the sometimes-dramatic rise and fall of water levels in the main body of the St. Lawrence.

The sanctuary’s original mandate to provide a place to protect and observe migrating waterfowl has broadened, largely through the efforts of groups with a vested interest in seeing its potential continue to develop. It is very much a work in progress.

Both the managing St. Lawrence Parks Commission and a volunteer group, the Friends of the Sanctuary, offer an expanding range of camping opportunities and public educational programs. Under the guidance of the Friends, the sanctuary’s trail network is groomed for snowshoeing and cross-country skiing, providing a much-needed “off-season” element by which to engage public interest and develop the sanctuary’s year-round potential. An active winter feeding program draws high numbers of black-capped chickadees and white and red-breasted nuthatches, all willing to alight and take sunflowers seeds from an open hand, offering the closest contact that many visitors will ever have with a songbird.

The original—and perilously rotted—boardwalks crossing the sanctuary’s fingers of wetland have been mostly replaced, and provide a stable platform from which to view an array of marsh activity that in recent years has included the early-autumn stopover of Great Egrets and, last year, a pair of Sandhill Cranes.

As part of a grassland habitat restoration project, the fields adjacent to the visitor’s center are being managed to provide suitable conditions for the Eastern Meadowlarks and the Bobolink—two species under threat from changing land-use practices in the area. This newly naturalized area is a welcome addition for birds, birdwatchers and cyclists using the section of the St. Lawrence Waterfront Trail running through the sanctuary.

The Stephanie Grady Pavilion, at the trailhead, commemorates the life of a local teacher and provides a sheltered environ for children’s programming. Along the sanctuary’s trails, benches and markers constructed at the local high school offer respite and direction.

Six decades on the sanctuary is exactly as it was first formed, and yet it moves.

Still-evolving

Unique circumstances created the Upper Canada Migratory Bird Sanctuary. Where it was once a populated area with a distinct riverside history, it has become a regionally-important public site where wildlife conservation is seen and experienced in tandem with the lessons of a broader history. Out of a flood emerged a new landscape and the opportunity to build a unique environmental legacy along the St. Lawrence that weaves the past into a still-evolving and promising future.

By Craig Irwin Stevenson

Craig Irwin Stevenson grew up in Cornwall, Ontario, and spent an inordinate amount of time on and along the River, at his maternal grandparents’ cottage, on Moulinette Island, the easternmost of seventeen islands created by the Seaway flooding. He is a history teacher at Tagwi Secondary School, in Avonmore, Ontario, and never misses a chance to tell his students that the River they see today, was once a very different place.

Be sure to see Craig Stevenson's other TI Life articles about building the St. Lawrence Seaway: Seaway 60th stories: The Seaway’s 60th, Part 3: Working at Height, The Seaway’s 60th and The Seaway’s 60th, Part 2: Another Look at a Lost River as well as '59 Forward: An Essay on the St. Lawrence Seaway After 60 Years.