When we think of animal extinction, we may consider the recent US Fish and Wildlife Service announcement removing 27 species from the endangered species list by declaring them extinct throughout their range. Most of the animals delisted were birds and mussels, two particularly vulnerable taxa. Of the birds, many were island species, mostly from the Hawaiian Islands chain. During the last 600 year period of European expansion, the majority of animals made extinct by humans and their camp followers, such as cats and rats, are island dwelling species.

Island birds are particularly vulnerable to invasive species habitat destruction and predation because of their biology and limited range. Oceanic islands once harbored many birds that lost their ability to fly and thus were among the first victims of the onslaught of the bipedal primates with opposable thumbs. Over the last century and a half, the eight-fold increase in human populations and development of mechanized tools to alter landscapes is further exasperating our impacts on continental land masses. Because of fragmentation in land use patterns, much of the world’s land masses are now “habitat islands” of various sizes. This is one factor profoundly affecting the world’s wildlife.

In continental areas, the march toward possible large scale population reduction of birds begins with local expiration. Population fluctuations are often very natural and species may disappear and reappear at various sites on the landscape. When human-caused major changes in habitat occur, however, this can lead to local expiration of sensitive species. Prime examples in our region are Bobolink, Eastern Meadowlark, and the now endangered Upland Sandpiper. A half century ago the range of these birds in northern Jefferson and St. Lawrence Counties, as well as adjacent Canada, was nearly continuous during the breeding season.

Their songs and the wolf whistle of the plover could be heard from virtually everywhere in June, throughout the grassy hay lands. Alas, not any longer as intensive modern row crop agriculture, with its landscape of chemical soup and multiple annual cutting of remaining grass, has all but eliminated these birds’ reproductive success. So instead of a contiguous range for Bobolink and Meadowlark, the birds now occur in a series of separated areas, much like islands. The plover, once common, is now well on its way to extirpation locally and in much of the Northeast. While these local declines may not result in species range-wide extinction, they are a troubling warning signal and very dangerous to the species when occurring over large landscapes.

The study of population declines and extirpation/extinction have been greatly aided by the development of the science of island biogeography. Pioneering biologist Robert MacArthur, working with a suite of wood warblers on islands in Maine, developed the basics. Among the items proven were that smaller islands have less diversity and a greater probability of local expiration in their fauna. This has been supported by many studies since the 1950s, and is one of the important tenets of conservation biology. Although pioneered on islands, its application to now fragmented continental landscapes is clear.

In the Thousand Islands Region, with our myriad islands of various types and sizes, one can observe natural limited faunal diversity and natural fluctuations in action. A study of mammals back in the proposed winter navigation era illustrates the dispersal limitations of species that can’t fly. While the large islands of Wellesley and Grindstone have a full complement of resident mammals, many small islands may have only a single species, the meadow vole, or none at all. Even though birds are more mobile, the same general pattern applies. The smaller the area, the more limited the available resources, and thus the smaller species diversity.

When humans occupy smaller islands they may actually improve the habitat available for adaptable birds. A structure added provides a nest site and potential food for an Eastern Phoebe pair. Addition of a lawn may bring American Robins who will also nest under structure overhangs. But along with these winners, there are also losers. The presence outside of owners and particularly Fido may eliminate the Spotted Sandpiper pair previously present. Also, the Great Blue Heron may change its fishing pattern to avoid disturbance from residents.

Islands such as Black Ant were once nesting sites for colonial waterbirds, until humans moved in, forcing the birds to move out and thus permanently losing nesting sites.

Given the complexities of wildlife conservation in our human-altered world, the knowledge derived from an understanding of the principles of ‘habitat islands’ is very helpful. These principles have led to the development of corridors to facilitate wildlife movements, on both a small and large scale. A great example of the potential of the latter is the Algonquin to Adirondack (A2A) project. Much of the Eastern Lake Ontario/ St. Lawrence River Region is a critical part of this connection between two significant wilderness areas. Locally, the Thousand Islands Land Trust is leading the charge on this effort to prevent regional extinctions.

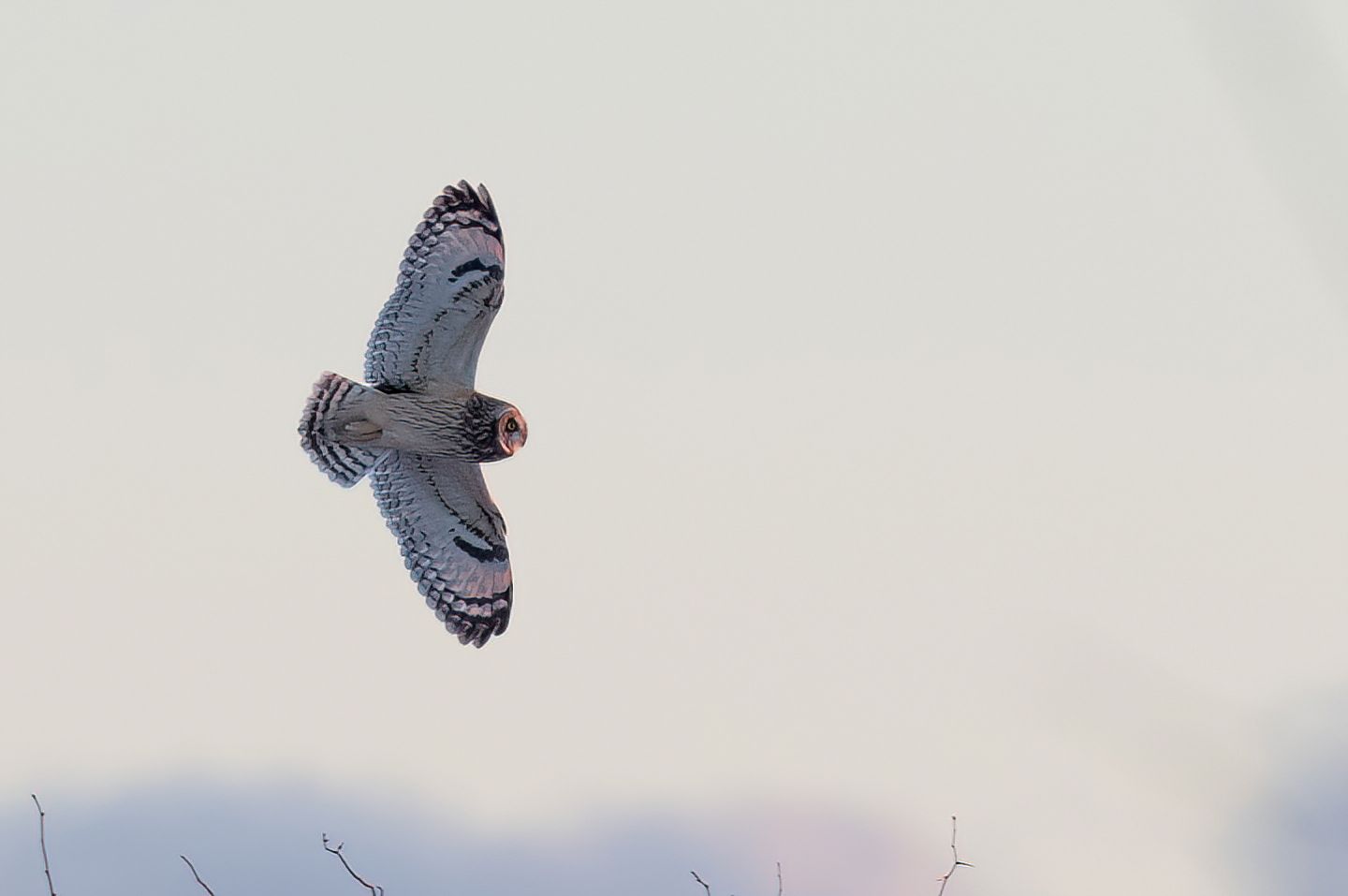

Modern conservation biology knows a great deal about how to slow or prevent local expiration and thus the major population declines that might lead to extinction. Unfortunately, the causes are often so complicated and the land use politics such a mire that progress is difficult. Three grassland raptors are excellent examples of the complexity of the problem locally. The seriously declining American Kestrel, threatened Northern Harrier, and endangered Short-Eared Owl, are all great examples of the problems that we face. In addition to the previously mentioned agricultural pressures, widespread use of rodenticides and habitat loss of remaining grassland areas are killer threats to the continued regional population of these species.

Also, the proposed conversion of large areas of some of the best grassland in the state to solar farms is a major new threat. At the moment, these facilities are in the pipeline for 14,000 acres in Jefferson County and 12,000 acres in St. Lawrence County. While we all are concerned about climate change, that is certainly not the only environmental conservation threat. In fact, the Great Lakes Region has been listed as one of most resistant parts of our continent to the impacts of climate change. We need to assess all aspects of conservation through a broad approach, not simply focus narrowly on one problem. Statements such as, “We solve climate change, we solve all conservation problems,” have been made recently by a high ranking official of a renewable energy group. This is not only inaccurate, it’s just plain silly. Renewable energy is not necessarily green and deployment of large complexes must be carefully done to avoid the very bad unintended consequences. We must avoid throwing many aspects of environmental conservation ‘under the bus’ in the name of combatting global climate change.

So, as conservationists have known since the modern natural resources movement began, you are often “damned if you do and damned if you don’t.” Today, we have far more tools at our disposal than did those who were unconcerned at the loss of the Great Auk, or those who barely saved the Bison and Whooping Crane. The reality is that there are no simple solutions to complex problems; renewable energy development, modern agriculture practices, rodenticide, and many other human practices require careful and detailed consideration of their impacts on other species. Failure to consider the impacts of each technology, before implementation, always leads to problems. Combined with human greed, it usually guarantees more local and regional extirpations of sensitive species, trending toward something much worse.

[*Extirpation: VERB root out and destroy completely]

By Sherri Leigh Smith

Sherri Leigh Smith is the Senior Ornithologist in northern NY. He is passionate about birds and their conservation. Sherri Leigh has written numerous articles for TI Life, and you can see several of them here.

Posted in: Volume 16, Issue 11, November 2021, Nature

Please click here if you are unable to post your comment.