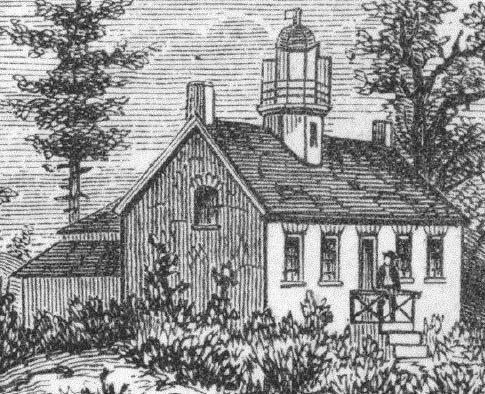

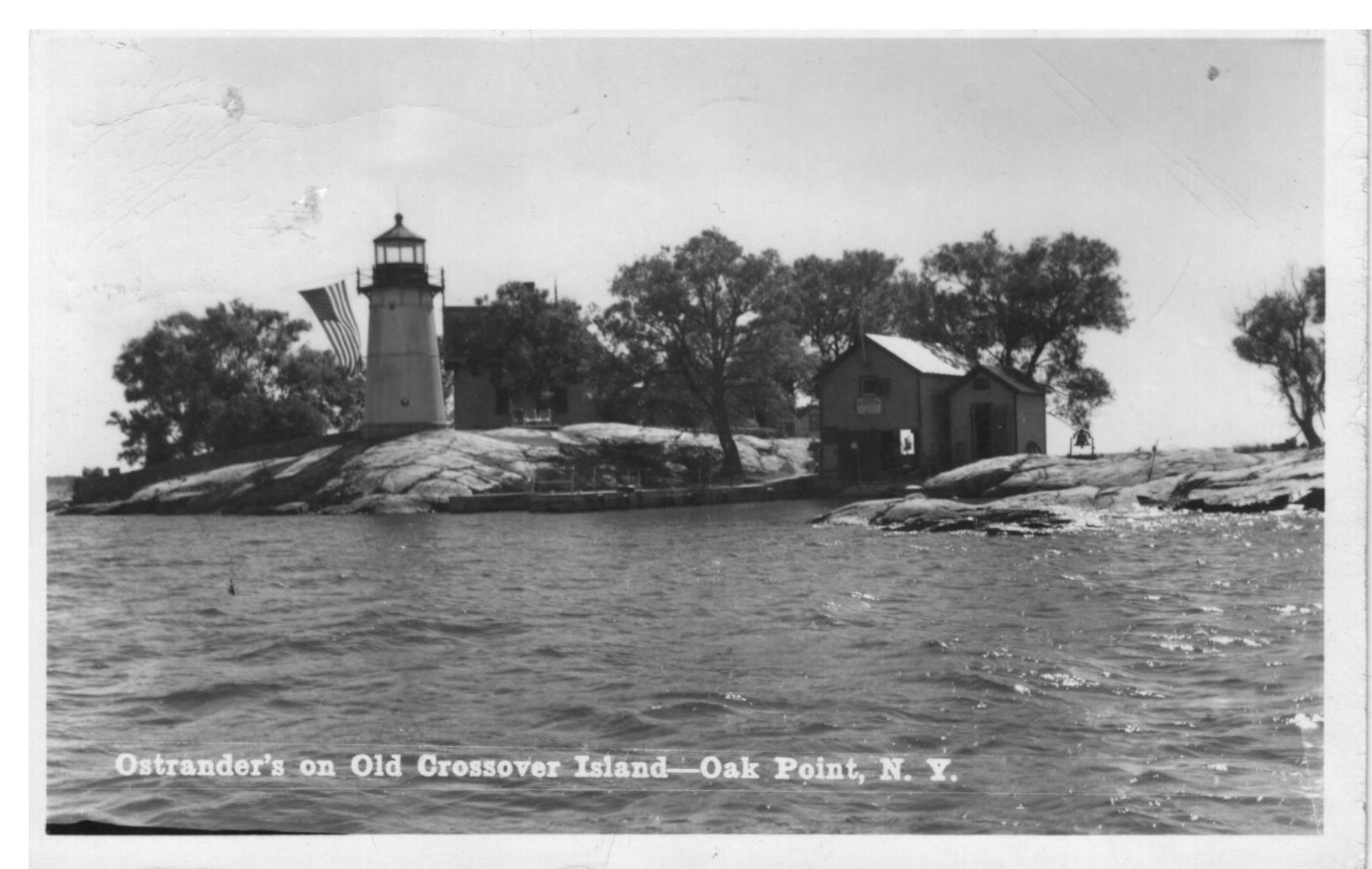

The first lighthouse on Crossover Island was mostly likely a duplicate of the one built a year earlier on Rock Island, and all later references seem to support that conclusion. It is described as a one-and-a half-storey brick dwelling with a wooden tower emerging through the roof at its center, at a height of 10 feet. A sketch of the Rock Island lighthouse by Benton Lossing, published in his 1868 Pictorial Field Book of the War of 1812, depicts that structure and gives us a good idea how the one on Crossover Island would have appeared.

Crossover Island is located a bare 1/5th of a mile south of the border, close to the point where the shipping channel crosses the international boundary. The lighthouse was needed to safely guide ships through the cluster of shoals and islands. Pressure for a lighthouse on Crossover Island began in 1838, but it was not until 1848 that the funds ($6,000) were provided, and the structure built. The first keeper was Obed Robeson. Only two decades (and three lightkeepers) later, problems were significant. An 1869 report from the Secretary of the Treasury noted that:

“This station has been put in good condition. Boat-house and ways have been built, woodshed repaired, shutters put on the windows, plastering renewed in both house and tower, and chimney-tops renewed. The isolated position of this station has made repairs more than usually expensive.”

The repairs were a temporary stopgap, however. From the report of the Lighthouse Board in 1872:

“The tower and dwelling are both in very bad condition, and are not worth repair. The tower is of wood, and rises from the roof of the brick dwelling; the timber is so decayed, and the interior framing so badly arranged, that water finds its way into the interior at all points of the connection with the roof. The brick of which the old dwelling is built were originally very inferior, and have been so injured by frosts that the walls are now unserviceable, and cannot be used for supporting any new work. They were sheathed on the outside with boards, in 1869, but this was a temporary expedient, serving only to relieve the cold and dampness of the dwelling, until the whole could be renewed. An appropriation of $11,000 is required for a new tower and dwelling.”

The following year the call was renewed, and the estimated cost was put at $14,000. This went on for several years, until 1879, when the Lighthouse Board report stated: “A tower should be built, detached from the dwelling. It is recommended that an appropriation of $5,000 be made for that purpose.” The reason for the huge reduction in cost is never addressed or explained, but the lower cost may be part of the reason that the call finally began to make headway.

In 1882, the old structure finally made way for a new light tower and a detached keeper’s dwelling. The tower was a thirty-foot tall iron tower, very similar to the ones erected the same year at both Sunken Rock and Rock Island lighthouses in the Thousand Islands. From the (1882) Lighthouse Board report:

“The tower rests on a floor of concrete placed on the smoothed surface of the rock of the island, and is lined with brick to the first landing, and above that with wood. The order of this light will be reduced from the fourth to the sixth order, and the present lens will be put into the Presqu’ile outer tower.”

And from 1883:

“The new iron tower was erected, the old dwelling was taken down, and a walk was built leading from the tower to the dwelling. A trap-door was placed in the lantern-deck. A storm-house was built over the front entrance of the dwelling, the wood-shed and old kitchen were moved to the rear of the new dwelling, and certain minor repairs were made.”

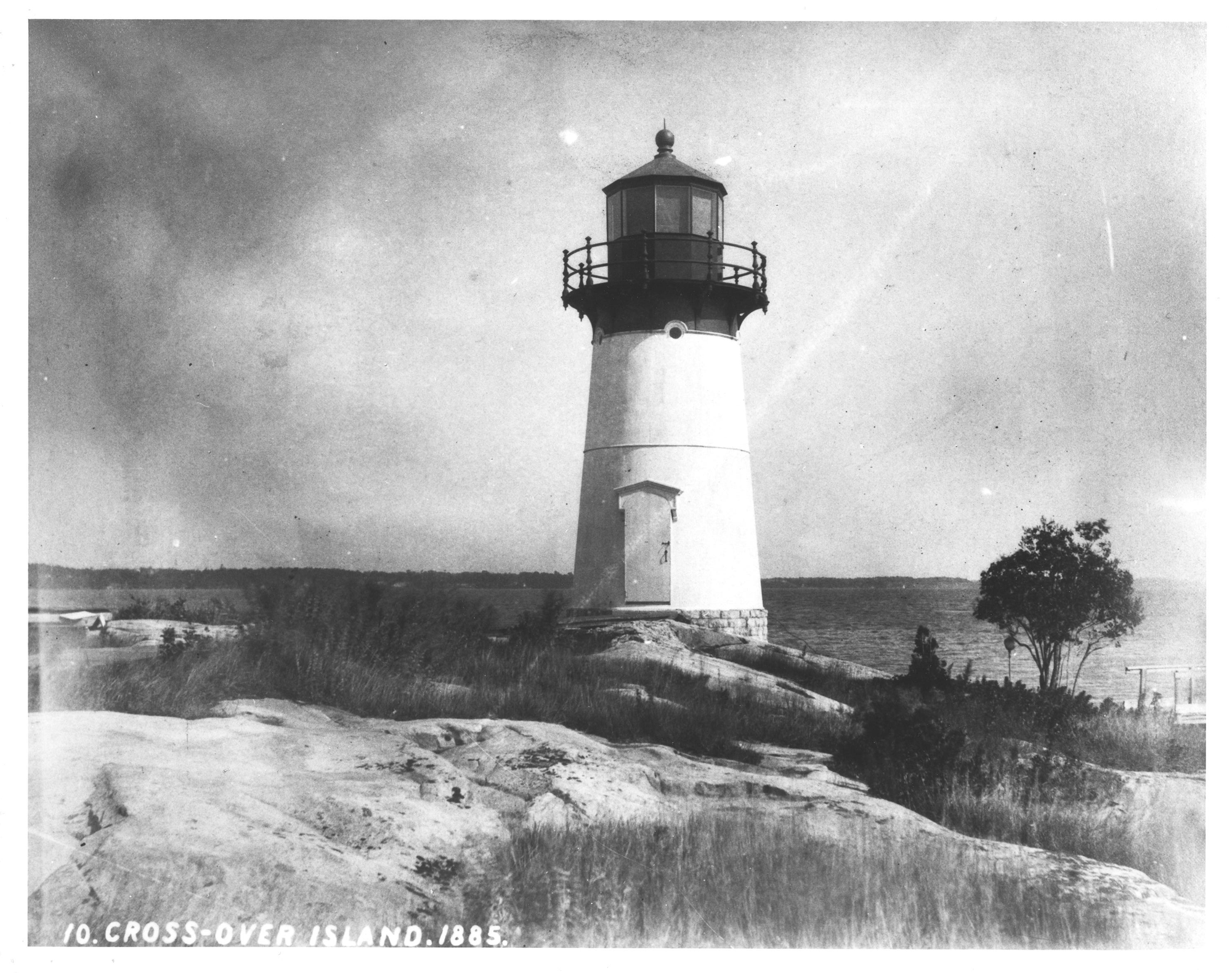

The old reports, gathered from various sources, are often inconsistent or contradictory in the information that they provide. So, while the lower half of the iron tower was lined with brick taken from the old dwelling (according to this same report from the Lighthouse Board), an earlier report by the Board (1872) blames those same bricks, being “very inferior,” for the deterioration of the original structure. Perhaps they were acceptable for interior use. Also of note is that several sources interpret the 1882 quote to mean that the exterior of the tower, above the second floor, was clad in wood. This is, of course, an erroneous interpretation: the upper portion was lined (inside) with wood, as is clear from a careful reading of the text and from all images. And a final point of confusion: what color was the tower painted? According to the Lighthouse Board, the tower was originally painted brown until 1899, when its color was changed from brown to white. Yet an image from the National Archives clearly shows a white tower in 1885 (an 1885 image of Rock Island Light shows the same). There are images of both Rock Island and Sunken Rock in brown paint, so it is certain that the tower at Crossover was also brown at some point, but the exact dates remain elusive.

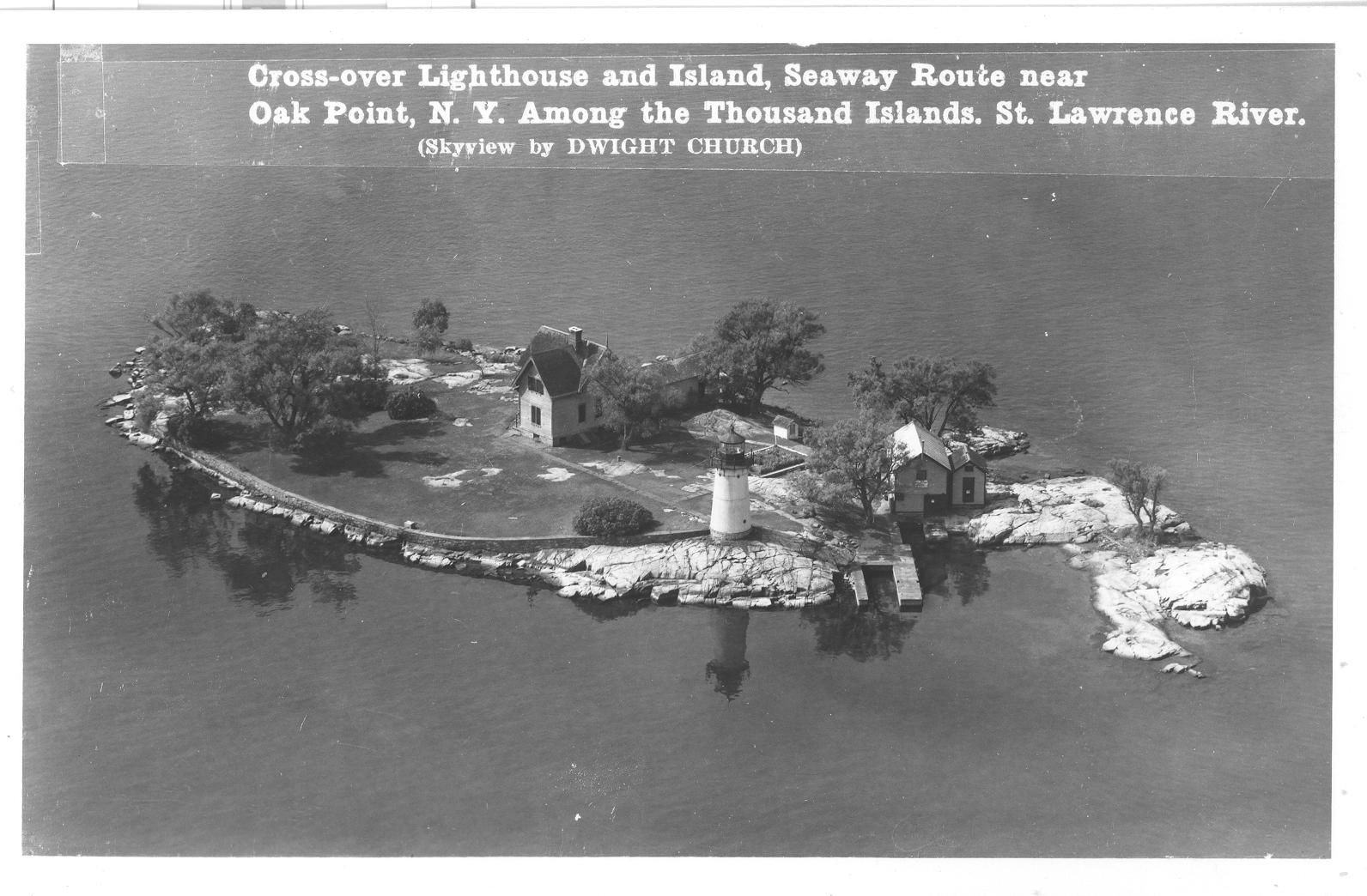

From this point on, the tower and keeper’s dwelling have not changed substantially in appearance. A well was sunk in 1884 (wells were also sunk that same year at Sunken Rock, Rock Island, and Sackett’s Harbor). A gale on January 13, 1890, destroyed the barn, which was rebuilt by the keeper. In 1896 a wooden 70-barrel cistern was built in the cellar of the keeper’s dwelling to replace an old brick cistern. The old ice house and the boat ways were also rebuilt. An oil house was added in 1904.

In 1900, some 300 cubic yards of earth were delivered to the island and spread around, filling depressions in the area of the lighthouse. This effort was stepped up in 1903, when:

“A masonry wall 232 feet long was laid up in Portland cement, partly around the island, to increase and protect the arable area. About 35 cords [166 cubic yards] of good soil have been filled in behind this wall for grading purposes.”

And in 1905:

“The earth filling inside of the stone sea wall was removed for 32 feet and leaks were stopped with concrete, after which the earth filling was replaced.”

This effort has made a lasting alteration to the island’s landscape such that, aside from the area of the light tower itself at the north end of the island, much of the island is relatively level and supports a lawn.

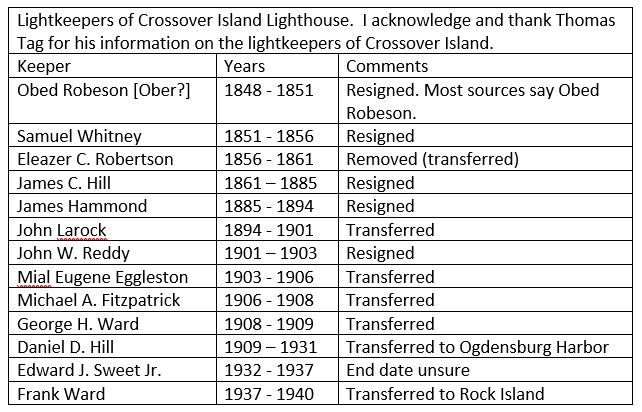

Lightkeepers:

The island saw numerous keepers come and go during its history.

Lightkeepers of Crossover Island Lighthouse.

Lightkeeping tended, in both the United States and Canada, to run in families. We see the keeper’s duties handed from father to son with some frequency, and sometimes from a man to his surviving widow (the only way a woman was generally assigned to lightkeeping duties). At Crossover Island, James C. Hill was followed 24 years later by Daniel D. Hill. 1880 census records for James C. Hill showed that he had a son Walter, so Daniel D. Hill (born in 1878) may have been a relative, but was not his son. George and Frank Ward, however, were from a family of lightkeepers. George’s father, James Ward, was a keeper, and three of George’s sons (Frank, Edwin, and Oswald) would serve at various lighthouses on Lake Ontario, including those at Rock Island, Tibbett’s Point, and here at Crossover Island.

Daniel Hill’s son Ralph wrote a book about life on Crossover Island. Some of his reminiscences centered on the keeping of the lighthouse, including details about the work of keeping the light tower always a bright white, alternately by scrubbing the outside of the tower with brown soap or by repainting it. He described the very thorough annual inspections by the district lighthouse superintendent, which included “checking inside the house, under the beds (!), in the clothes closets (and) the kitchen cupboards.” He also mentioned the stringent accounting for every single item supplied by the government (from old paint brushes to empty oil cans to old sponges), the destruction of which had to be witnessed by the superintendent, to prevent the sale of government property.

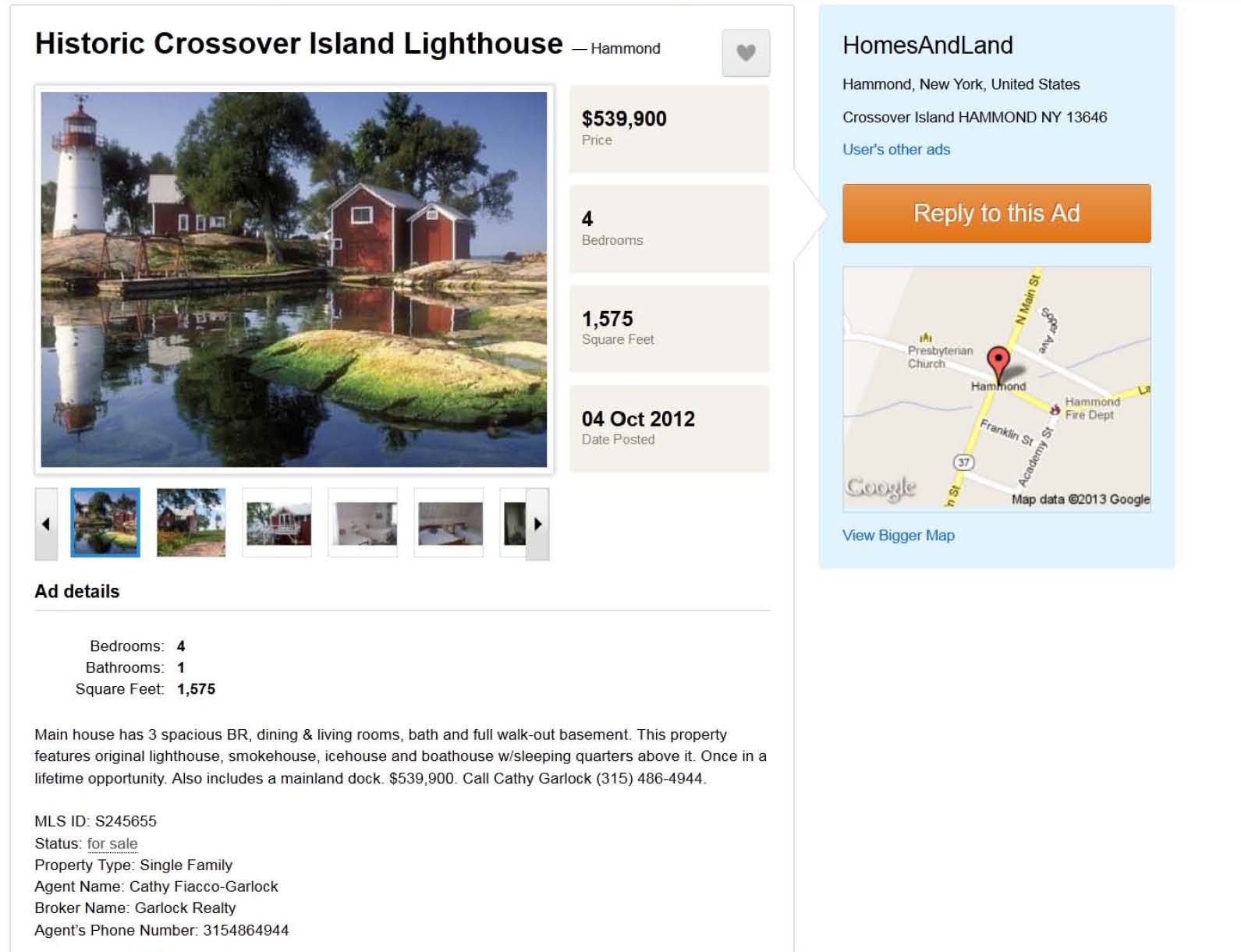

The era of the lighthouse keeper came to an end when Frank Ward was transferred to Rock Island Lighthouse, and Crossover Island lighthouse was discontinued on April 10, 1941. The government eventually declared the station surplus to its needs, and in 1960 it was sold to private owners, three Edwards brothers.

In 1969, it was sold to the Dutcher family, who owned it for many years afterwards. In 2002, it changed hands again, being purchased by John Urtis, who in turn gave it its most recent offering in 2011.

It eventually sold in 2013 for a reported $350,000. In 2007, the lighthouse was added to the National Register of Historic Places as Crossover Island Light Station. The island is readily viewed from the water, but please remember that it is private property if you choose to visit, and do not trespass.

[Header © Photo Ian Coristine/1000IslandsPhotoArt.com]

By Mary Alice Snetsinger

More about Mary Alice Snetsinger, ecoserv@kos.net

Mary Alice Snetsinger grew up in the United States and Canada, and worked for four years at Thousand Islands National Park. She became interested in the 19th century lighthouses of the Thousand Islands in 1997 and has been researching them ever since. Mary Alice provided TI Life with articles about Wolfe Island’s Lighthouses, Fiddler's Elbow, Lindoe Island Light, the Ogdensburg Harbor Light and Cape Vincent Harbor Lighthouses; click here to see Fthese articles and here to see the latest three, Spectacle Shoal light, Sisters Islands Lighthouse and Sunken Rock Light.

Editor's Note: Our thanks to Mary Alice who never ceases to find interesting and unknown facts about these iconic lighthouses of the Thousand Islands! We are honored to share this information to TI Life readers.

Posted in: Volume 16, Issue 7, July 2021, History, Places

Please click here if you are unable to post your comment.