TILT’s Island-wide Conservation Initiative Nears Completion

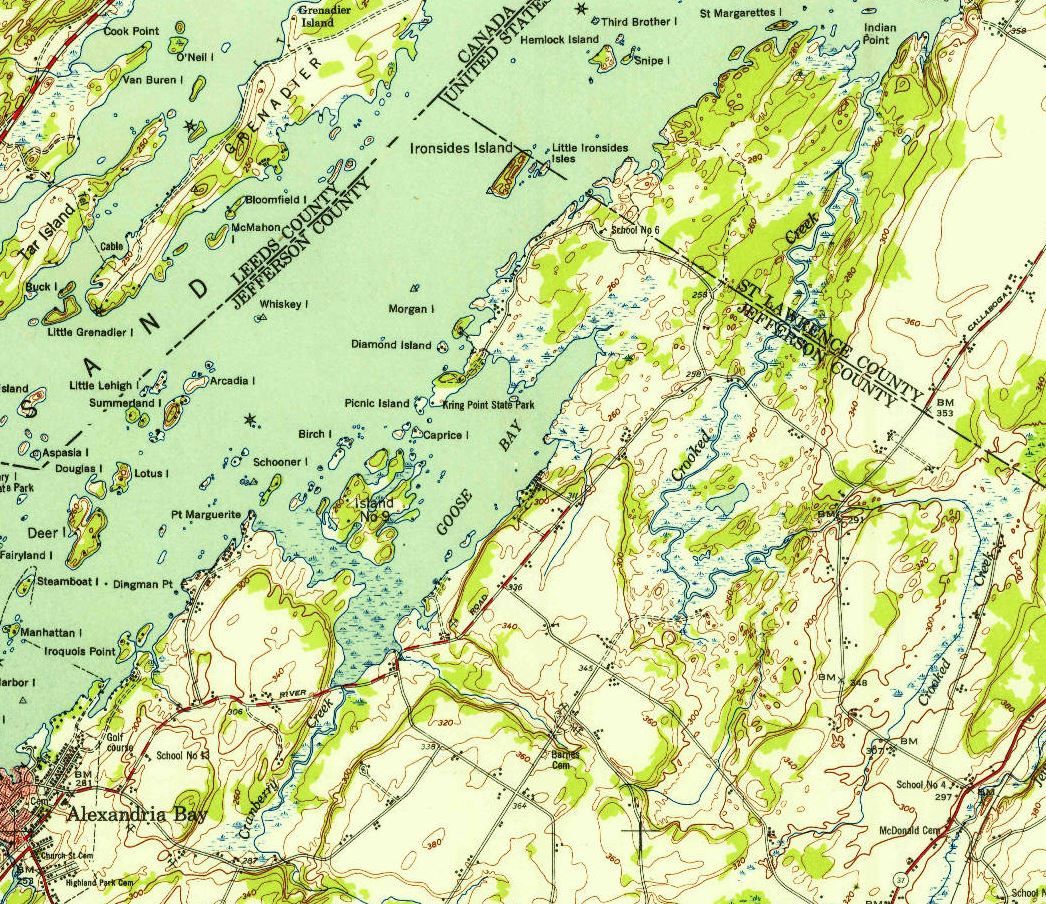

When looked at from afar, one might question if Number Nine Island is actually an island at all. The dense cattail marsh spanning the distance between the mainland and the island’s western high grounds make it appear as though the entire area is a wide peninsula protruding into Goose Bay, as if to mirror Kring Point. Many who enjoy boating the River have traveled the narrow waters between Number Nine and Kring Point. Known as the Goose Bay gap, this channel is the gateway between the popular flat water bay and the St. Lawrence Seaway.

Island Number Nine, an amoeba-shaped tract of land, does in fact qualify as an island. Many recount stories of small boats circumnavigating Number Nine during high water years, carefully making their way through an expansive marsh that separates the island from the mainland. In fact, the 1948 US Geological Survey topographic maps show Number Nine as being fully independent of the mainland.

Through this marsh, historians tell of the dramatic escape of American seamen who were blockaded by British vessels during the bloody Battle of Cranberry Creek in 1813. With British ships anchored at the Goose Bay gap, the American seamen were able to escape their stronghold on Cranberry Creek by sneakily poling their skiff through the marsh. Once in open water, the American vessel was able to open its sails en route for Sacket’s Harbor without tipping off the British ships waiting in the gap. Without question, passing through these marshes by boat would be impossible today, since it is now fully choked with a hardy stand of hybrid invasive cattail.

Depending on where you delineate the obscure boundary between upland and marshland, the island itself encompasses about 160 acres of hard ground. Every square foot of Number Nine has something extraordinary to offer, from its exceptional fish and wildlife habitat, to its unparalleled scenic quality, and its one-of-a-kind past. A quiet walk through the island’s mature oak-pine forest will confirm its unique ecological diversity and history. Rusted remnants of century-old farm implements are camouflaged on the vibrant forest floor. These tools and a few stray strands of barbed wire are now the only remaining clue that the Island was once a working farm.

Over a handful of decades, nature has prevailed once again. Colorful fungi slowly decompose the wind thrown logs that the ruffed grouse use for drumming. The overhanging canopy rains acorns into the protected open water marsh pockets. A step too close and the feasting dabblers flush. Earlier in the summer, a deafening songbird chorus is broadcast from this canopy. Later in winter, bald eagles perch above it, atop the tallest pines. Regardless of time of year, Number Nine provides an asylum for the region’s flora and fauna.

This past November, the Thousand Islands Land Trust (TILT) moved one step closer to its island-wide conservation goal for Number Nine Island in Goose Bay. With the addition of a new parcel, TILT now conserves 117 acres of the amoeba-shaped island and is under contract to protect an additional 45± acres around the Island, including about 45 acres of the marsh that separates Number Nine from the mainland.

TILT began the process of conserving Number Nine Island in 2019 and in the winter of 2020 was awarded a grant through the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation (NYSDEC) Water Quality Improvement Program (WQIP) for the priority conservation initiative: Number Nine Island in Goose Bay. Through this grant, TILT is working to preserve nearly 160 acres of forest and wetland on and around this island, which ultimately will protect the water quality of the St. Lawrence River.

From the headwaters at Lake Ontario to its confluence with the North Atlantic, the St. Lawrence River and its tributaries provide drinking water to hundreds of thousands of people across countless municipalities in the US and Canada. As impacts from shoreline construction and agricultural degradation continue to be felt across the entire Great Lakes basin, there is increased susceptibility for water contamination by nutrient-laden sediments and other harmful pollutants.

At the local level, aside from the risk to safe recreational enjoyment of these waters, this means that municipalities and other public water suppliers eventually would need to implement more robust and costly treatment systems in order to provide clean, safe, drinking water.

Over the last few decades, water quality in Goose Bay, in the Town of Alexandria, has been on the decline, likely due to increased nutrient loading associated with waterfront development and agricultural activities in the upper watershed.

Most of the land surrounding Goose Bay is composed of very shallow soils, which do not absorb nutrients well and therefore are not able to treat sewage and wastewater properly. These abundant nutrients that are not absorbed in the soil make their way into open water, causing the explosion of aquatic weed growth that we see now in Goose Bay. Here, invasive weeds are flourishing, hindering boating, swimming, fishing, and dock access. While local citizen groups are working diligently to combat this growth with aquatic herbicides and other removal techniques, these efforts do not address the root of the problem of poor water quality. Excess nutrients can also lead to harmful algal blooms (HABs) in Goose Bay’s shallow, slow-moving, and warm water, posing a health threat to humans, pets, and wildlife.

“The Island’s natural riparian vegetation and coastal marshland acts as a filter, cleaning runoff of excess nutrients and pollutants. Maintaining clean water in Goose Bay and the St. Lawrence helps safeguard the region’s natural resources and tourism-based economy,” states Jake Tibbles, TILT’s Executive Director. “By conserving these properties, TILT ensures that they remain in their natural vegetated state in perpetuity, free from additional pollutant sources. The conserved riparian areas will also serve as stabilizing agents and buffers by retaining moisture and reducing erosion during high-water events.”

According to the 2018 study conducted by the Trust for Public Land and reviewed by Clarkson University entitled “The economic benefits of preserves, trails, and conserved open spaces in the 1000 Islands region”, conserved open spaces such as Number Nine Island have a positive impact on nearby residential property values in that people are willing to pay more for a home close to these amenities. This ultimately translates into greater property tax revenues generated annually from homes adjacent to these protected spaces. “Residents choosing to call the Thousand Islands home value being close to the Region’s preserves, trails, and conserved open spaces. Be it a family home near Zenda Farms Preserve or a summer cottage near one of the several State Parks in the Region, these amenities create additional value across our local communities,” explains Martin D. Heintzelman, Associate Professor at Clarkson University.

Local property owners understand the importance of conserving Number Nine and the impact that the Island has on the ecological and fiscal health of the area. This summer, David Garlock worked with TILT to conserve 34 acres of his land on Number Nine. “I moved to Number Nine Island seventeen years ago because of its secluded location and spectacular beauty,” says Garlock, “It’s a comfort to know that TILT will keep the Island natural, balancing future development with conserved open space for many years to come.”

As TILT’s acquisition efforts on Number Nine draw to a close, its stewardship responsibilities are just beginning. Public access to the newly established preserve will be organized through TILT’s Treks and environmental education programming.

By Spencer Busler, Director of Land Conservation, Thousand Islands Land Trust

Spencer jBusler joined TILT in 2016 as Director of Land Conservation. He holds a Bachelor of Science degree in Natural Resources Management from the SUNY College of Environmental Science and Forestry as well as a master’s degree in Water and Wetland Resource Studies from the same institution.Previous to TILT, he worked along the St. Lawrence with the US Fish & Wildlife Service and Lafave, White & McGivern, L.S., P.C. He grew up in Theresa and spent the vast majority of his childhood summers on the numerous waterbodies of the Indian River Lakes chain where he developed his deep appreciation for our natural surroundings.

Spencer looks forward to contributing to the continued protection of the diverse natural resources of the Thousand Islands ecosystem.

This article was originally published in the Thousand Islands Land Trust Newsletter and on their Website. Another example of how conserving land helps the River and in turn our Thousand Islands lifestyle.

Posted in: Volume 17, Issue 1, January 2022, Nature, Places

Please click here if you are unable to post your comment.