Winter Raptors are Coming

by: Sherri Leigh Smith

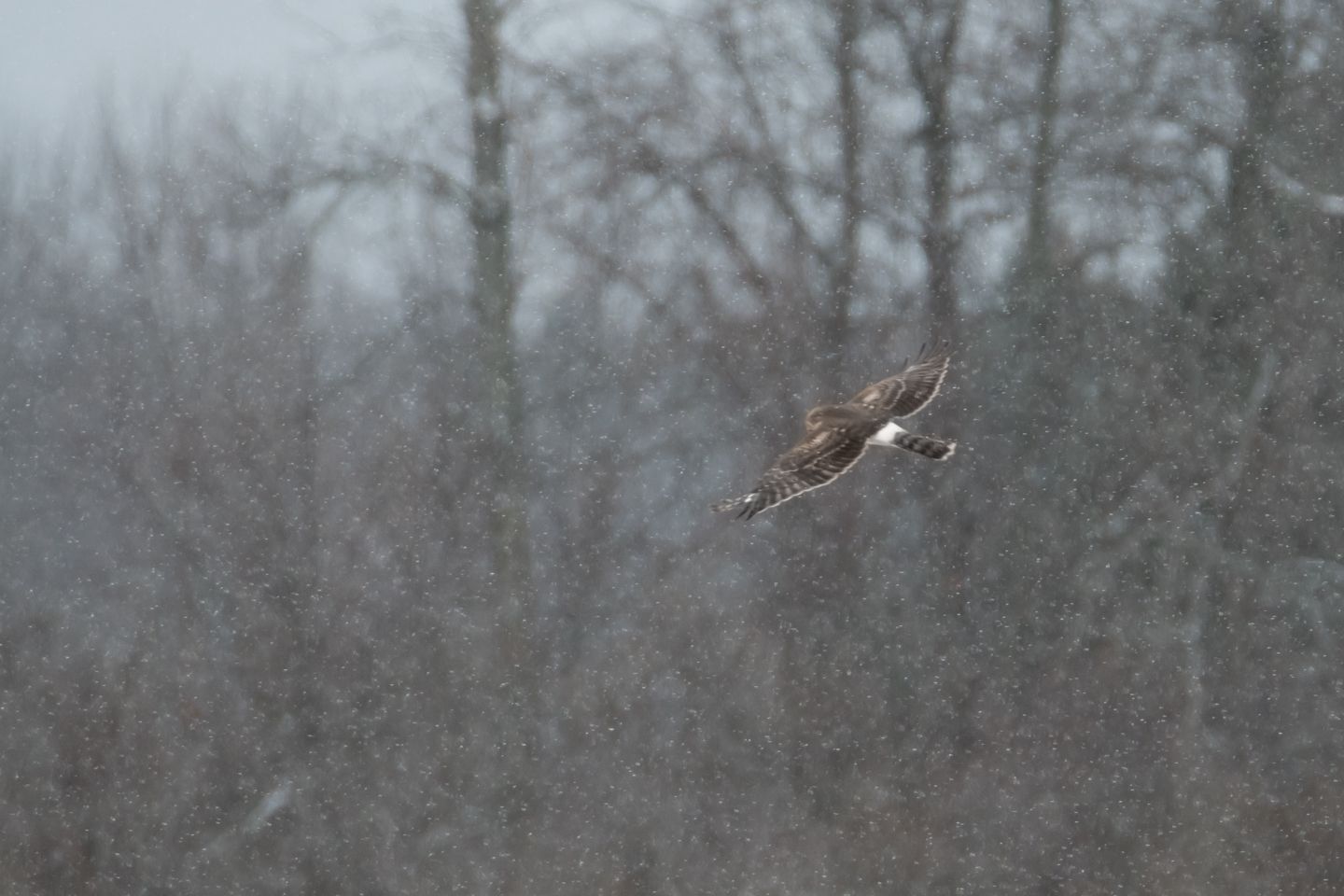

In November, many of the northern raptors that winter in the eastern Lake Ontario and western St. Lawrence region are settling in. Mouse raptors, including Rough-legged Hawk, Northern Harrier, and Short-eared Owl, will be passing through. If it’s a good year for an abundance of meadow vole and other small mammal prey, many will winter with us. In years when small mammals are scarce, few winter, with most continuing their travels in search of food. This situation varies greatly from year to year; thus, it’s difficult to predict the abundance of raptors that will attempt to winter until US Thanksgiving.

Fall and early winter raptor migration is poorly known in the Thousand Islands region. East of Prince Edward Point, Ontario, and north of the south shore of Lake Ontario, there is little information on active hawk flights. One day the birds simply appear at traditional wintering areas where they may remain for hours, days, weeks, or months. The three previously mentioned species, along with Red-tailed Hawk and lesser numbers of American Kestrel and Snowy Owl, make up the bulk of wintering open country raptors in our region. In recent years the exploding Bald Eagle populations have made this species one of the most common winter birds of prey, particularly during years of small rodent scarcity.

As noted, populations of these species vary significantly from year to year due to many factors. In addition, to local conditions on the northern breeding grounds such as prey availability, breeding success, and summer weather, greatly impact populations. Northern species, particularly arctic ones, go through boom and bust cycles. Based on prey availability, in some years, a pair may produce several young, while in others, they may be completely unsuccessful. Thus, the number of birds wintering with us is a complex interaction of ecological factors, including habitat conditions locally and those hundreds to thousands of miles distant.

Within our region, certain areas are particularly favored by wintering mouse raptors. These include Point Peninsula and the Towns of Cape Vincent and Clayton in New York. In Ontario, Wolfe and Amherst Islands often have hosted large raptor concentrations. Other sites, including Galloo Island, Stony Island, Grenadier Island, and Carleton Island in New York, probably attract wintering raptors, but their inaccessibility makes that hard to confirm. Fortunately, the last two islands are primarily protected and managed by the Thousand Islands Land Trust, so any wintering raptors are safe from habitat disruption. Undoubtedly there are other lesser-known concentrations, and some birds may be found in suitable habitat throughout the region.

Just as the factors that produce good winter raptor numbers are dynamic, so are locations where these birds may be found. In the last two decades, there have been profound changes to wintering habitat in many parts of our region. In any given year, rodent cycles may vary greatly at sites separated by only a few miles. The proliferation of intense row crop agriculture that has replaced traditional grasslands is severely impacting habitat quality for these birds. In essence, the wintering mouse raptor community is comprised of grassland open country birds when they are with us. Anything that degrades or replaces grassland habitat reduces local carrying capacity to support the needs of these hawks at a critical time in their life cycle.

Just how critical abundant prey and quality habitat are to populations of these species can clearly be observed during a good raptor winter. In such winters, fifty to seventy percent or more of individuals present are birds hatched the previous summer. Catching live prey is a tough challenge, and young birds must acquire these skills rapidly or starve. In some years, half to three quarters of young hawks and owls do not survive to their second year. Thus a young bird finding a meadow vole bonanza greatly improves its odds of survival.

Based on my more than a half-century of hawk observations, it’s clear that immatures need lots of practice and all the help they can get. Attempted predation on fast-moving prey has low success rates even among adults. Try catching a mouse with your hands, as I have, and you appreciate the difficulty. For immatures, the success rate of kill per attempt may be only one in twenty or less. Therefore dense vole populations provide more opportunities for hunting skills and better odds of avoiding starving to death. Since birds on their first flight south have no previous wintering area, encountering a vole plague in the Thousand Islands Region is a raptor Valhalla.

Even in the best years for wintering raptors, numbers present usually decline as the season progresses. For the Northern Harrier declines may be rapid and caused by a major snowstorm. This species is very snow depth-sensitive, and a half of a foot of fresh powder triggers a mid-winter exodus to less snowy climates. Since these birds are in good shape due to abundant food supply, they are capable of a mid-winter emigration, something smaller songbirds are not. Undoubtedly some mortality of individual raptors occurs even in good years as well as limited emigration occurring in most species. Thus, local peak numbers usually occur between late November and mid-January, with a gradual decline thereafter. By late February northbound migration is underway.

Although numbers of these species that occur in our area are highly variable, my impression is of a long-term decline over the last forty years. This is well documented for Northern Harrier and Short-eared Owl and, in my opinion, is occurring for Rough-legged hawk and Red-tailed Hawk. In the complex ecological mess of the 21st-century one can only speculate why, with certainty, hard to come by. Are northern Buteos staying farther north as a result of climate change? Have invasive diseases such as West Nile Virus impacted populations? Is habitat degradation from agriculture and renewable energy reducing the carrying capacity for these birds in our region? Whenever populations of any wildlife species decline, there are usually multiple causes. I do not understand all potential causes, but, in my opinion, species such as Rough-legs are generally less common than they were a quarter-century ago. Such potential declines are a cause for concern and require conservation actions such as grassland protection and management.

There are few sights in the natural world of settled Eastern North America as an assemblage of large birds of prey. In past decades I have seen dozens to more than 200 wintering birds of prey in the towns of Lyme, Cape Vincent, and Clayton. Similar numbers occur on the Canadian side of the region. These concentrations are among the largest in Northeastern North America. To the large grassland areas not filled with corn, soybeans, wind turbines, solar panels, or other habitat-destroying items must be maintained and preserved. If we do so, future generations may thrill to the sight of dozens of Rough-legged Hawks, Northern Harriers, or Short-eared Owls entering or leaving a communal roost. Watching these raptors interact with each other as they jockey for position in the nightly chaos is better entertainment than any film I have ever seen.

By Sherri Leigh Smith with photographs by Julie Covey

Sherri Leigh Smith is a senior Ornithologist, Avian Ecologist and Conservationist, working to preserve bird populations in Northern New York State.

Julie Covey, Nature in NNY (https:www.facebook.com/NatureinNNY/)