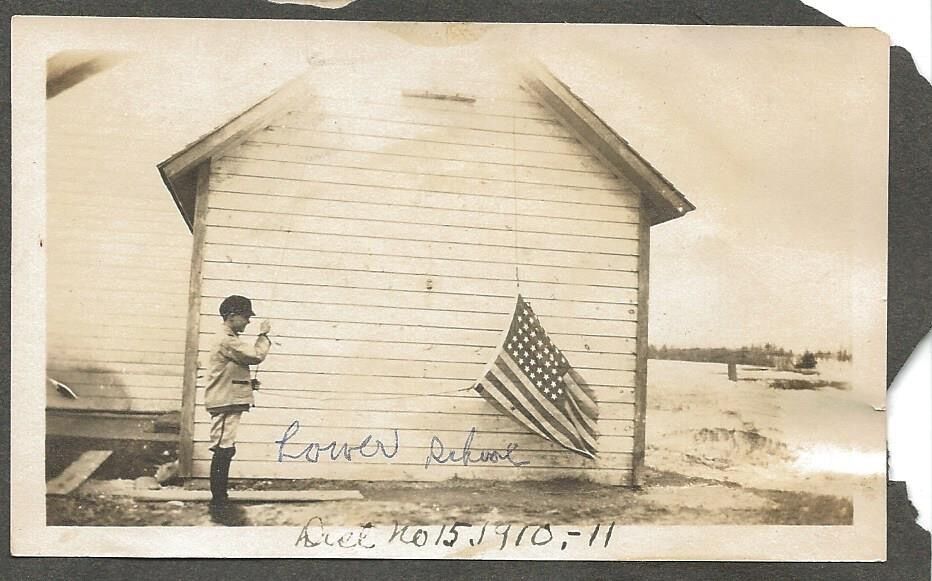

Almost halfway across the width of Grindstone Island was the Lower Schoolhouse. The structure sat on a parcel of land donated by A.E. Potter, a prominent farmer who I believe lived across the road, sometime in the early 20th century. Early photos show a number of my family who attended the little school. By the 1930’s, many of the early family names had disappeared – families had moved away, died, and in some cases no longer had children of school age.

Some of my oldest memories of the school include the uncut grass of the school yard. It was about an acre of land, enclosed on two sides along the road by a rather curious woven fence. It had two gates – one for foot traffic, and one for wagons or cars, which were supported by post cemented into the ground so deeply that frost never heaved them from the ground. At the only door, cemented into the step, was a boot scraper; at the time I never realized that I would see that scraper 1500 times over the next eight years.

To my left there was a rather large piece of tin, flat and securely nailed to the white siding. What it hid underneath, was never known to me. I entered there on my first day of school, escorted by my Aunt Carnie (Carnie Rusho Hammersley), who was also a student. We were surrounded by a group of other kids who I did not know, everyone talking and laughing, excited to see each other after the summer break. I was ushered into a large part of the building, separate from the school classroom, which had two windows and nothing else, and a door that led to the classroom where I would spend eight or more years being educated – or somewhat so.

Into the unknown I went, a huge room with windows on the right, too high to escape through, and no doors to the rear. I was trapped. The wood floor was freshly oiled, and it would be a long time before the odor of the oil went away. My aunt seated me next to her in a large desk, the top covered by carvings that consisted of initials, weird designs, some full names, and more. A huge clock was fastened to the east wall, its pendulum swinging back and forth with loud clicks.

At 9:00 the teacher struck her desk with a large ruler. I ducked down closer to my aunt, afraid of what was to come next. The teacher welcomed the students back with a pleasing voice, and began roll call. The teacher did not have horns, and there was no whip, contrary to my aunt’s previous description, although the large ruler was enough. I noticed that there were no older boys in the room, maybe a few 10 or 12-year-olds, but the students were mostly girls from my age to my Aunt Carnie’s, who was an ancient 13 years old at the time!

Further inspection of my new environment revealed two large pictures, both of men. Who they were and why their pictures were hanging in a school room, I had no idea. The large clock ticked away ever so slowly – only ten minutes had gone by. I wanted to ask a question and was hushed by my aunt, who gave me a book with pictures to shut me up. I continued to look around the room; straight ahead of me was the blackboard with a few words and names written there. Most made no sense, except the teacher’s name “MRS SNELL,” which was written in long hand and in big letters and that she pointed out.

To the left of the black board was the complete school library, just five shelves of books that were a mystery to me at the time, but eight years later, I would have read almost all, if not all, of them, and many more. On the left side of the room was a thing, a shelf with a drain; sitting on the shelf was the pail that held the drinking water for the school. Protruding from the pail was a dipper, the drinking cup for the entire student body. Behind the water pail was a door, but where it led to was a mystery. Later, I found out that the door led to a small room where students hung their coats in cold weather.

At about 10 am, the door opened and four older boys came in, saying that they had been home doing chores. Since they all lived on farms it was possible, but the older girls knew better and said so – laughing loudly! The teacher sent them to seats, separating them from each other. My aunt and the other older girls knew all of the boys and said that they were just trouble, too lazy to do school work and too young to quit school.

My aunt’s desk was the furthest from the teacher; behind her was the rear wall of the classroom, to her left and one seat away was the stove, a large barrel-like thing. Under the stove was a metal shield to protect the floor. The pipes from the back of the stove went upward to a brick chimney that did not sit on the floor, but was supported by two large planks with shelves containing books or papers. A big rope hung from the ceiling; in the ceiling, there was a hole and the rope disappeared into the hole. There were four lamps hanging from chains in the ceiling. I fell asleep soon after 11:00, and when I awoke it was lunch time, everyone was outside, the uncut yard stopped no one. I shared a sandwich with my aunt. Afterwards, someone came to pick me up and my school day was over.

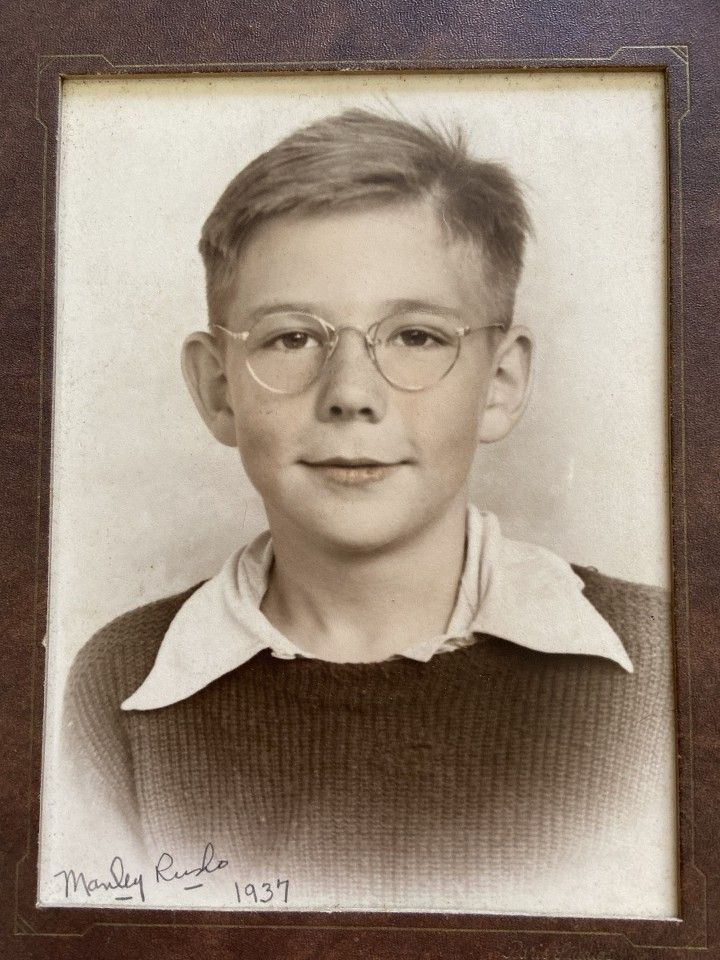

I am sure the year was 1936, and I returned to school with my aunt many times that year. I guess you could say it was kindergarten. When my 1937 school year came, indoor toilets had been built on the rear of the building, boys and girls on one side of the addition and a coal shed on the side toward the road. The old outside toilets were gone, but the grass in playground yard was still uncut. We received Coca Cola pencils from the school board and 12-inch rulers, also from the Coca Cola Company.

Our playground equipment was usually a few tennis balls furnished by Paul Carnegie, who worked for some summer people who played tennis. I discovered three names carved in the new addition; Ben Calhoun, Mel Calhoun, and Will Clark, which were dated 1936. One year, we received a fire extinguisher of sorts, it was a glass thing that hung between the shed door and the cloak room door. There was also a globe that was suspended from the ceiling, which replaced the pull-down window shade maps.

Many things imprint a memory, such as the fact that the coal bin door could be locked. I remember my Aunt Carnie helping Mary Carnegie escape through the small window after the teacher had locked Mary into the coal bin for some reason. The endless games of Alley-Oop, throwing a ball over the shed part. In the winter, we played Fox and Geese, with a huge circle stomped into the snow with crossed lines like spokes in a wheel. In the early summer, the wild strawberries would be ready to pick and eat across the road. New swings and teeter-totters in the play yard. Finding former students names from long ago written on the galvanized fence post. The water pail stayed the same and so did the dipper. Housing for the teacher in 1950 included an add on or rather an expansion of the old shed, but no running water – still used the pail.

I left the old school house in June 1944, after completing the 8th grade. That September, I was a 9th grade student in Clayton Central School. There were lights that you turned on or off with a switch, store bought floors, desks that were not fastened to the floor, and each class had its own teacher. Water fountains that you pushed a button and the water came out of a small thing to drink. Indoor toilets that flushed and wash stands where you could wash your hands. There was a gym, windows that you could see outdoors, paved roads, telephones, and electric street lamps – a world 180 degrees from Grindstone Island. Small wonder that many Grindstone students could not stand the culture shock of the Clayton school and quit school.

I was compelled to endure the winter on the mainland because the River was too wild to cross. I shoveled sidewalks to keep busy and could earn fifty-cents a sidewalk. After a heavy snow fall, I could pocket $5 or $6, which would buy movie tickets, Cokes, and candy bars. I would often walk to the town dock; straight across the River was my home on Grindstone Island, in plain sight, my Island. My heart was there and still is.

It was a long winter, but by mid-March the River was free of ice, and me along with other students that came from the island could once again spend nights at home with family back on the island. Reflecting back, the Clayton School Board educated students until 8th grade on the cheap - no buses, no maintenance, no water bill or electric bill, no special teachers, no staff, no grounds, no nothing. It was too good to last.

By Manley L. Rusho

Manley Rusho was born on Grindstone Island nine+ decades ago. Back in 2021, Manley started sharing his memories with TI Life. (Manley Rusho articles) This Editor and his many friends send our very best as we know he was not able to return this summer, but we want him to know summer and the regular and new groups of River Rats all enjoyed a Grindstone Island summer. We also want him to know "we are thinking of you Manley. As always, we thank you, most sincerely, for sharing - as the life and times on Grindstone Island are special and should never be forgotten."

Manley Rusho articles

Note: The Grindstone Island Lower Schoolhouse was purchased by Manley and his late wife Mary Lou in the mid 1990’s. They renovated the dilapidated building and used it as a guest house for many years. It is now owned by the Grindstone Island Research and Heritage Center and is the Grindstone Island Heritage Museum. It is open to the public in the summer months. www.grindstoneisland.org.

Posted in: Volume 18, Issue 9, September 2023, History, People, Places

Please click here if you are unable to post your comment.