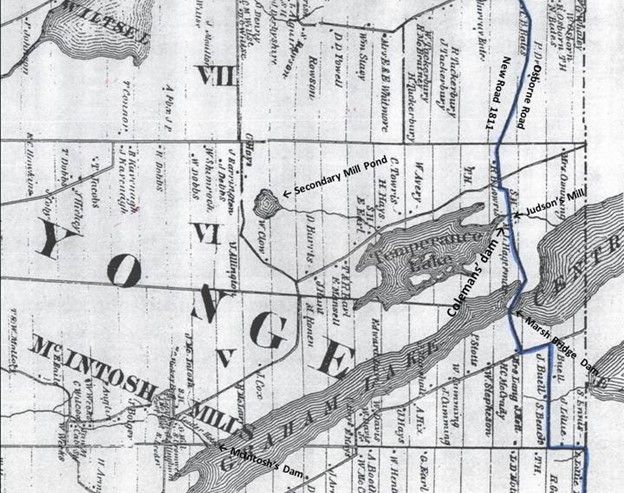

This largely forgotten story began in the 1830s, but not in Gananoque, as one would expect. It began with Richard Coleman Sr. in what is now a quiet rural community called Lyn, a few miles northwest of Brockville, Ontario. In the early 1800s, the Coleman family had been attracted by the great falls at Lyn and its manufacturing potential. Although the waterfall was about 50 feet high and ideal for milling operations, it lacked a steady water supply. It was Richard Sr. who hatched an ambitious plan to divert water from ‘the hinterland’ to feed the mills at Lyn. To do this, he would have to create a water diversion project such as Leeds County had never seen before, except the Rideau Canal. This immense project involved damming several lakes in Yonge Township to increase their height, and then diverting that excess water via a canal to East Lake just north of Lyn, which did flow to Lyn.

The key to the whole project was Temperance Lake, as the water from that lake and its tributaries flowed to a then small Graham Lake, immediately to the south. Temperance Lake is about 20 ft higher than the other lakes. In 1836, Richard began buying up the water rights around the lakes from the local farmers, beginning with the purchase of Judson’s mill at the mouth of Temperance Lake. Richard Sr launched the project but died before it got too far. The project was then taken up by his sons, Richard Jr and James, in the 1850s. They continued it with a rare determination. It was the sons who initiated the dam building part of the project.

The amount of engineering was mind boggling for that time. There were seven dams in all. The one at Temperance Lake raised the water level by five ft, but the greatest engineering feat was building a retaining wall at the west end of Graham Lake at McIntosh Mills, which raised the level of the Lake by seven ft. The levee was fifteen to twenty ft above the original grade, about 30 ft wide at the top and ran for about ½ mile. It is hard to imagine how many horse-drawn wagon loads of fill that must have taken. This levee has survived very well for the last 170 years, still holds back this artificial lake, and it is easily spotted on google maps. They also built a dam at the east end of the lake (the Marsh Bridge dam) to control the water flowing from Temperance Lake and created a new lake called Centre Lake (known locally as Stump Lake).

At the east end of Centre Lake, they built another dam to control the outflow to the newly dug canal to East Lake. For the 1850s, it was an immense and expensive undertaking. The brothers didn’t skimp on the construction quality. Some of these dams are still functional after 170 years. Others have been altered to suit current needs. Leeds County has seen nothing like it since. But there was one thing the brothers didn’t take into account.

The water didn’t belong to them.

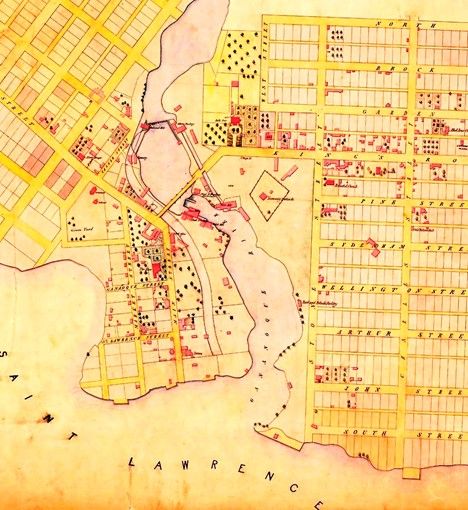

All the streams and lakes in the northern part of Yonge Township were part of the Gananoque River watershed, so all the water flowing to Gananoque was considered a part of their water rights. By the 1850s, Gananoque was an industrial powerhouse. Although it was jealous of its water rights, the owners were ‘asleep at the switch’ regarding stewardship. They had lost part of the watershed to the Rideau Canal in the 1820s and weren’t about to lose even more of their water supply. If that weren’t enough to raise the hackles of the Gananoque industrialists, the Coleman brothers then did something inexplicable. In 1856, they bought the dam site at the Outlet from Charleston Lake, and the site at Marble Rock, just north of Gananoque. These sites were in the hands of a competitor and not the easily influenced local millers. There was no way that the waters of Charleston Lake or the Gananoque river system could be back flowed to Lyn. For example, Charleston Lake was about 70 ft lower than Graham Lake. But this move gave the brothers a choke hold on all the water flowing to the mills at Gananoque. They might have gotten away with their scheme in Yonge Township, but their incursion into the heart of the Gananoque watershed meant war. They were now a direct threat to the water powered industries in Gananoque.

William Stone McDonald, a grandson of Joel Stone, the town’s founder, and some of the other mill owners (David Ford Jones, Isaac Briggs, George Mitchell, William Ellison Potter, and Robert Webster) took the Colemans to court in 1858 and won some crushing concessions from them. This case wasn’t tried in a local court, but at the Court of Chancery of Upper Canada, which later became the Superior Court of Ontario. The Gananoque group ended up with 68% of the outflow from Temperance Lake and dictated how the dams were to be modified (at the Colemans expense) to distribute the water to that effect. And the waters of Graham Lake were to be solely for the use of Gananoque. The debt that the Colemans had accumulated, plus the conditions of the lawsuit bankrupted the Coleman enterprise. In February 1862, their two major lenders, the Bank of Montreal and the Bank of Upper Canada, called in their loans, which in today’s money would be about two million dollars. The Coleman grip on Marble Rock was neutered in a separate 1859 agreement. The Marble Rock and Outlet dams remained under Coleman ownership for a while longer, but the control of the dams went to the Gananoque interests. As a face-saving gesture, the Colemans received £5 and a ¼ interest in a neighbouring lot. The Lyn enterprise was then taken over by other parties and continued to prosper, but Richard Coleman never got over the loss and committed suicide in 1868.

Legal documents extracted from the Abstract Indexes (land records) show that McDonald, along with the other industrialists in Gananoque, now realizing how vulnerable they were to competitors, made the first steps in forming the Gananoque Water Power Company, in August 1861. There was a series of overlapping agreements with other interested parties, to purchase shares in the new company. The number of shares each party owned determined how much water each shareholder was entitled to use in their factories. The name ‘Gananoque Water Power Company’ was not used in these documents, since it had yet to be incorporated. It wasn’t until 1878 that the company regained full legal control over the Marble Rock and Outlet dams.

The Coleman brothers had acted quite correctly in buying up the water rights on the lakes affected by their enterprise, before starting their flooding. The Gananoque Water Power Company hadn’t learned this lesson, so they had no such qualms. In the early 1880s, the company raised the height of the dams at Marble Rock and the Outlet, thereby flooding large tracts of farmland on Gananoque and Charleston Lakes. Apparently, the company thought it could get away with stealing land from the farmers. But the company hadn’t counted on the resolve of those farmers who were affected. The resulting lawsuit forced the company to pay out about one million dollars (in today’s money) in compensation in 1886. Hubris has its price.

The power company survived that setback and, as times moved on, it evolved into various companies, which included The Gananoque Light and Power Company, Gananoque Light, Heat and Power Company, and Granite Power, all of which were locally owned. The latest owner is Fortis, an international power conglomerate. It is worth noting, however, that beneath the Gan Light and Power Company building at 5 King St East, there is a functional, water driven, electrical turbine that was installed in 1939!

By Paul Coté