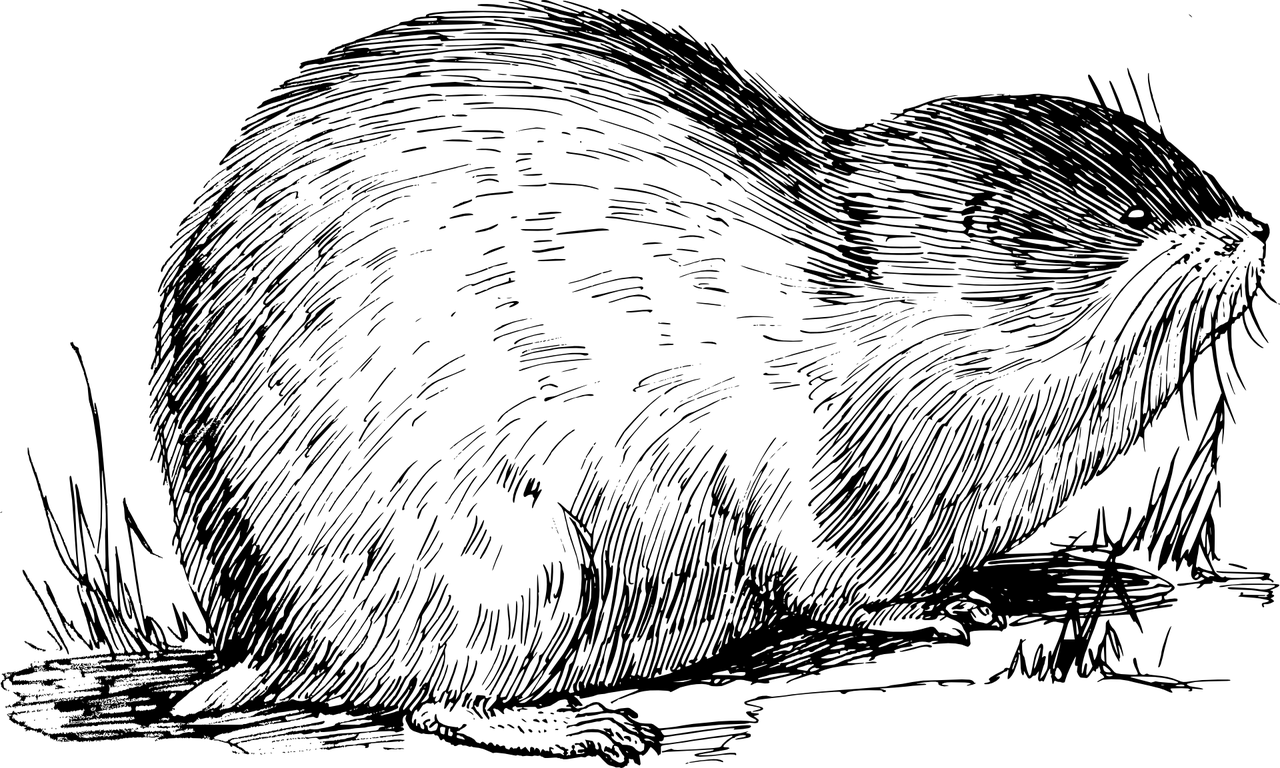

The Muskrat

by: Manley L. Rusho

If there was one animal that everyone on the island admired, it was the muskrat. An air- breathing, fur-bearing rat that lived and died far away from man. The rat lived its entire life in a water world, a pure vegetarian, consuming only the choice roots and shoots of the marsh grasses that provided his home, shelter, and his food.

The muskrat rarely interfered with humans, he built no dams, flooded no fields nor any roads and didn’t cut down any trees. As a source of food for foxes, hawks, and owls – the young muskrats were consumed by fish, raccoons, and Lord only knows what else. More remarkable, he lived everywhere that there was a constant water level. On the broad waters of the St. Lawrence River, he lived and multiplied. One of his favorite dwelling sites was the crib-like dock structures that protruded from the shore to the deep water along the river banks. Deep inside of the dock, a structure of seaweed grasses and sometimes marsh grass was fashioned into a freeze-proof house. These river dwellers were clam eaters and the only evidence they were there would be a pile of clam shells near the dock.

Along the shallow bays where dirt formed the bank, lived the bank dwellers. For my brother Milton and me, it was the marsh dwellers that we hunted with a passion. A Christmas gift started a lifetime of memories; twelve Oneida Victor single spring traps – bright and shiny. We learned that bright and shiny traps would not do, so the traps were placed in a cast iron pot and boiled for several days in a mixture of oak, maple, and cedar bark. Upon completion, the traps were a dull black or brown, they were rust proof, scent proof, and ready to catch muskrats!

I guess that our first season was a success because we caught one muskrat – it was skinned, the hide was stretched, dried, and sold for more than the traps cost. Our traps were then put away for the season, that is the summer – well not quite – we extended the trapping season to include wood chuck, and yes, even the odd skunk or two. Our trapping skills were now honed, especially the setting of the trap. We learned that a slight error would bring the jaws of the trap up your fingers – very unpleasant to say the least!

By Christmas, the marsh was frozen enough to carry the weight of my brother and me and we were back on the hunt for the muskrat. This is where he lived, the evidence was all around – houses and push-ups were everywhere. The rat houses made of marsh grasses at times rose 4 feet above the frozen surface. Those houses were not to be broken into in order to set a trap and that was a rule that we always obeyed.

During this time, we attended the Grindstone Island Lower Schoolhouse, which was located on the other side of the marsh from our farm. That made it mandatory to attend to our traps on our morning walk to school. Often, we would arrive at school ladened with one or two dead muskrats, a few dirty traps, two hatchets, and sheath knives. The muskrats and the equipment were left in an unused portion of the school, almost unnoticed, they stayed there until we left for home. During this time, it was a normal way of life for us. We were unaware if we broke any laws, and on the way back home, our traps were reset for us to check on our walk to school the next day. We had to set the traps very carefully, to ensure that the feeders would not freeze, otherwise they would be useless.

When spring arrived on the island, we were ready for the muskrat to begin the mating season or run as we called it. We now had at least 100 traps in our possession, which we would set, some given to us and some purchased, all treated and ready to go. The muskrat season only lasted about two weeks; by then the aloof mating was done, the weather was warmer, and the rats had begun to lose their winter hide. Without the thick, winter coat the rat hides were almost worthless. We’d clean our traps and put them away until next season.

The sales of the muskrat hides became very lucrative for us. Our uncle, Benny Calhoun, made arrangements to meet at Rothenberg’s Clothing Store in Clayton. The store was owned by two sisters, although I only remember one of them, Hilda.

Into the store we went, with about 500 pelts piled on the floor; Uncle Benny had his pile, Lewis Calhoun had his, and my brother and I had ours. The sisters had made arrangements for a fur dealer to be there and he carefully looked over each hide. The inspection of each fur was tedious – there could be no animal fat on the hide side and the fur had to be perfectly dry. A monetary deal was finally made; Uncle Benny got his cut, Lewis Calhoun got his, and my brother and I were very happy with our cut of $5 for each pelt.

One successful season down, many more to come! Great memories of trapping muskrats and very profitable too!

By Manley L. Rusho

Manley Rusho was born on Grindstone Island nine+ decades ago. Last year, in 2021, Manley started sharing his memories with TI Life. (Manley Rusho articles) This Editor and his many friends wish him continued good health and we thank him for sharing - as the life and times on Grindstone Island are special and should never be forgotten.

Editor's Note: Manley just looking at the comments left on your articles makes me realize how lucky we are to have you sharing - much appreciated.