Spectacle Shoal and Red Horse Rock Lighthouses

by: Mary Alice Snetsinger

Spectacle Shoal and Red Horse Rock were among nine lighthouses established in 1856 when the government decided that lighting the Canadian Thousand Islands was a priority. Located southwest of Gananoque, and less than ¾ of a mile apart, both lighthouses were built on piers established on the rock shoals they were marking. Like the other lighthouses built that same year, they were small wooden towers, cheap to build and easy to move as needed, but also vulnerable to the elements. As early as 1860, Spectacle Shoal’s light tower was moved (likely only a few feet) onto a new crib; in 1888 a new crib was built under Red Horse Rock, and officials were advised that the same was needed again at Spectacle Shoal.

The Lists of Lights always recorded Spectacle Shoal before Red Horse Rock as they listed the lights from east to west, though Red Horse Rock was considered the more important of the two. A walkway connected it to Beau Rivage Island, where a lightkeeper’s house was built. Sadly, none of the nine 1856 structures remain today: the last to go was the Cole Shoal Light, near Brockville, which burned to the waterline following a lightning strike on the evening of July 25, 2018.

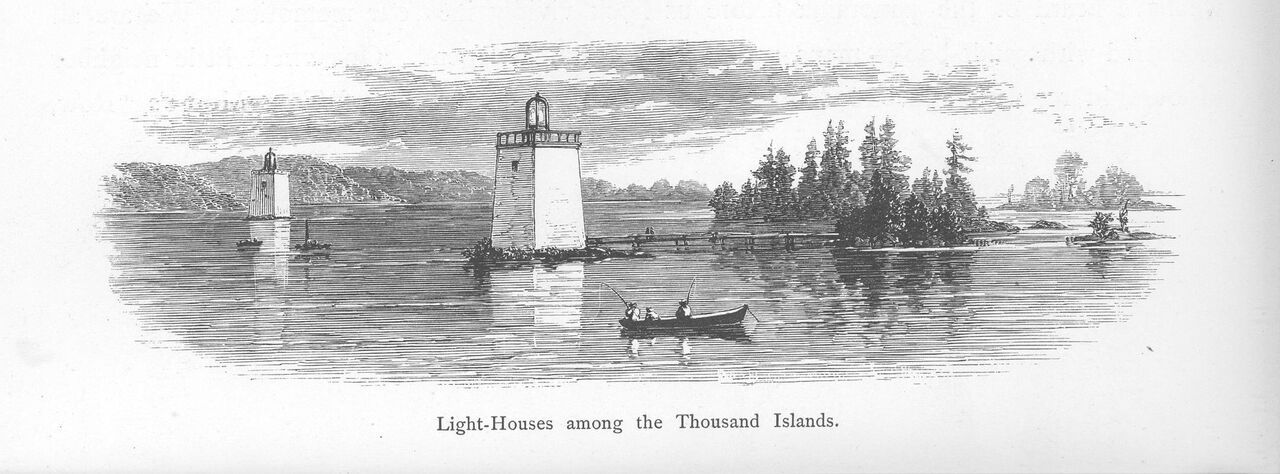

Early records of the towers portray them off-handedly as “built of wood,” and of “a small inexpensive description.” From the 1874 volume of Picturesque America, we get a very early image of these two lighthouses. Red Horse Rock is in the foreground, with its walkway providing a quick identification feature that helps to differentiate otherwise indistinguishable 26-foot high, white wooden light towers.

Like their counterparts at Gananoque Narrows and Jackstraw Shoal, the same keeper was responsible for both Spectacle Shoal and Red Horse Rock for their entire working history. The first few years saw a succession of lightkeepers (see table), but in 1864 John Buck was appointed, and would remain for sixteen years. He was well known in the area, and Beau Rivage Island was referred to as Buck’s Island in the annual List of Light for the Dominion. (The island was originally named Hurd Island, (named British hydrographer Thomas Hurd on the William FitzWilliam Owen survey, 1818), and was much later renamed Beau Rivage when it became part of the Thousand Islands National Park.)

Lightkeeper Dates

Hiram Cook 1856 - 1858

Daniel Bryant 1857 - May 1863 (died)

James Ward 1863

John Buck June 1864 - August 1880

William Jackson August 1880 - November 1901

John A. Landon November 1901 - June 1904

Manley Cross 1904 - December 1907 (died)

Mrs. Manley (Jennett) Cross January 1908 - May 1912

Abraham Meggs May 1912 - November 1924

Thomas Ferris 1925 - 1947

Despite being among the lowest paid government employees, lightkeepers had great demands put upon them. By 1865 the government decided to provide guidance in its “Instructions to Light-house Keepers.” The 1912 version lists eighty-four rules for lightkeepers, with another eighty-five rules for keepers operating fog alarms, eleven on the operation of cotton powder electric explosive fog signals, two on hand fog horns and bells, and eleven more regarding buoys and beacons!

An example: “The great art of keeping reflectors in order consists in the daily, patient, and skilful application of manual labour in rubbing their surfaces, beginning at the centre and gradually working outwards with a circular motion of the hand. If their silvering becomes dim, a little of the rouge powder may be employed, but no other material must under any circumstances be used.” Any scratches in the silvering were considered to result from carelessness, and the keeper was held accountable for them. Failure to fulfill the many duties was cause for dismissal.

Dismissals were not unheard of. A special government report on “Persons Dismissed, Removed, Superannuated, from the Public Services Since 13th February, 1879” listed reasons such as “negligence” and “absence without leave.” The following year, however, the official record states only that “By Order in Council on the 10th August last [1880], Mr. William Jackson was appointed keeper of the lighthouses at Spectacle Shoal and Red Horse Rock . . . in the room of Mr. John Buck, superceded.”

The Gananoque Reporter, however, provided abundant details. Over the course of February 1880, the paper reported that the Department of Marine and Fisheries was investigating charges against John Buck, detailing the charges and much of the testimony in the “Great Buck Hunt,” as the headlines proclaimed. On July 17th, the paper reported that John Buck had been dismissed on various grounds, including leaving the light without permission, and placing “intemperate and improper persons” in charge of them on several occasions. The paper concludes that “There seems to be but one opinion on this matter among the people of Gananoque of both political parties; and this is, that Mr. Buck has been most unfairly dealt with, and dismissed without real cause.”

In 1904, Mr. Manley Cross took over the lightkeeping duties at Spectacle Shoal and Red Horse Rock, when the government decided to convert the lighthouses in the region to acetylene fuel, allowing them to dismiss most of the lightkeepers. Manley Cross, who was already lightkeeper for Gananoque Narrows and Jackstraw Shoal, now had six of the area lighthouses under his care (Burnt Island and Lindoe Island being the other two).

When Manley Cross died at the end of 1907, his wife was appointed lightkeeper in his place. I have written about Jennett Cross in an article on the Gananoque Narrows and Jackstraw Shoal lighthouses. She is remarkable as having been the only woman to have served as an appointed lightkeeper in the Thousand Islands for more than a few months, on either side of the border. For four and a half years, until the government abruptly switched back to coal oil in 1912, necessitating the return of the dismissed lightkeepers, Jennett Cross had charge of six lighthouses. She continued on at Gananoque Narrows and Jackstraw Shoal lighthouses, but Mr. Abraham Meggs took over at Spectacle Shoal and Red Horse Rock in May 1912.

The last lightkeeper was Thomas Ferris. At the time he was appointed in 1925, he had already been lightkeeper at nearby Burnt Island for several years. He then acted as keeper for these three lighthouses until his retirement. When Thomas Ferris retired in 1947, the lighthouses became unwatched lights, and were converted to electricity. From the 1948 List of Lights, it appears that the wooden tower at Spectacle Shoal was demolished and replaced at that time: it describes Spectacle Shoal as a “Red, steel, skeleton tower on a pier in the river,” with a year of alteration as 1946.

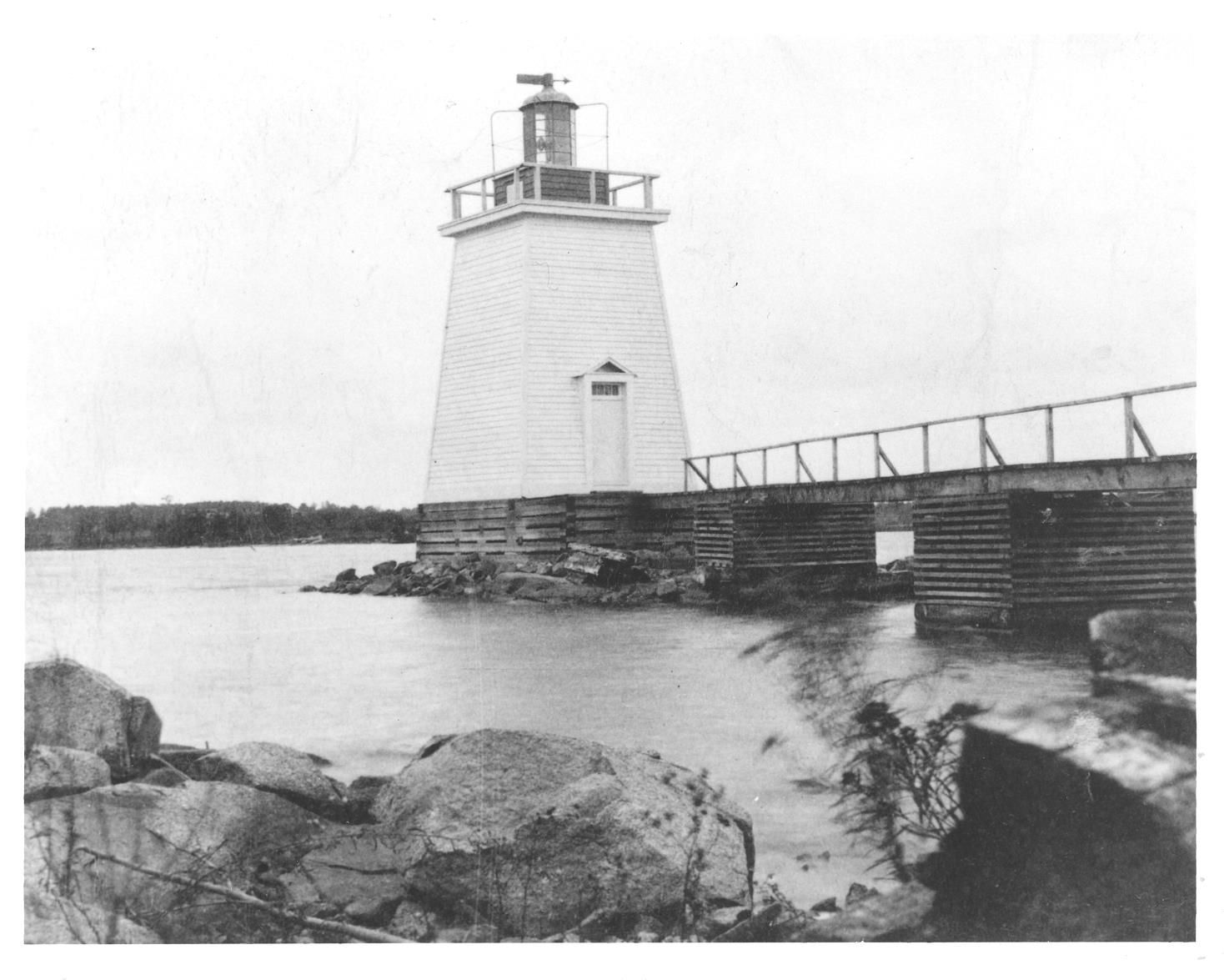

Red Horse Rock lighthouse continued to be a navigation aid for another two decades, and many area residents remember seeing the old tower. Images are also found on postcards from that time. Around 1954 it was transferred from the Department of Transport to the Department of Indian and Northern Affairs. In 1965 John Stevens, an architectural historian from the National and Historic Parks Branch, wrote an inspection report, noting that the lighthouse was the “most nearly original in condition of any of the older structures examined.” He described it thus: “about 12 feet square, with a medium taper. An old photo shows it on a timber cribbing, and connected to the nearest island by a walkway spanning several wooden cribs. At present, it is mounted on four concrete piers. The walkway has collapsed, and is unusable.”

John Stevens expressed hope that, if removed from active duty, the tower could be moved to one of the adjoining park islands and preserved. Despite this, Red Horse Rock light was lost in 1967. That year, as part of the Centennial celebrations, the Coast Guard was ordered to “clean up the river.” As described to me by Chuck Lemaire, one of his first jobs when he started as a navigation aids officer with the Coast Guard was helping to pull down the old lighthouses: a rope was tied around the tower, and the ship Simcoe simply hauled it off its footings. He remembered pulling down Red Horse Rock and Lindoe Island lighthouses specifically, but nearing forty years later he could not recall if there was a third one. A sad way to celebrate a country’s Centennial!