“The only thing that ever really frightened me during the war was the U-boat peril.” Winston Churchill

Last Sunday, my wife Cathy and I were honoured to be guests of Major and Mrs. J. Kent Stewart at the laying of wreaths at the Naval & Merchant Marine Memorial, for The Battle of the Atlantic Sunday. Carrying my wreath for The City of Kingston, a flood of memories came back to me, as Major Stewart escorted me to the memorial. Back to May 3rd, 2003 to be exact . . .

My wife Cathy and I sit with Ray and Lillian Wade in a comfortable restaurant in downtown Kingston. The Battle of the Atlantic is many years ago and not part of Cathy’s lifetime or mine. But for Ray and Lillian, it seems like only yesterday.

Speaking softly, Ray Wade points out that he made 56 trips in convoys to Britain, eventually working his way up to second mate status. Wade also remembers that first convoy, that first trip, heading out into the North Atlantic Ocean. With who knew what waiting for them . . .

. . . . . . .

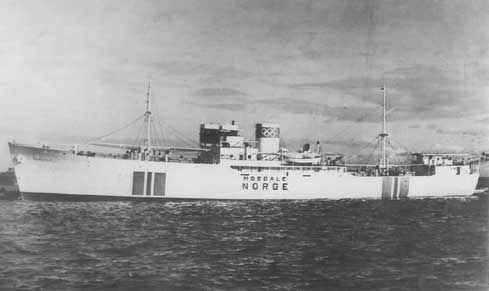

Far out on the North Atlantic, the three-castled Norwegian freighter Mosdale, three days out, was headed for England. The Mosdale, like all the other mostly Canadian freighters in the convoy, supplied food, munitions, and men to war-torn Britain, which by now was threatened with defeat and depending heavily on this lifeline from Canada.

Standing on her starboard quarter out of the wind, Ordinary Seaman Ray Wade, just off watch, leaned on a bulkhead and stared out at the sea. Timing himself and feeling the deck gently rise, he shifted his weight first to one leg and then the other as he met the long, gentle swell of the restless ocean.

Even now, in the late afternoon, he couldn’t relax. Sleep would only come later, with sheer exhaustion. Trip in, trip out, you were always on edge – especially at night with the ships shrouded in darkness. All of the ships would be darkened and he and his shipmates would be all alone – alone in a crowded convoy on a dark, merciless, empty sea while an unseen enemy lurked below, watching. Always watching and waiting. Sleep, when it came, usually was accompanied by nightmares of explosions, sometimes imagined . . . but too often real.

The grey, cloudless sky blended into the ocean until the horizon itself disappeared, adding to the emptiness. Behind every ripple and wave, Wade, like the lookouts posted on the bridge up forward, strained his eyes for that telltale break in the pattern among the endless roll of each wave. He was watching for the dreaded outline of a U-Boat periscope watching them. Watching and waiting.

For a few minutes, Wade’s thoughts ran back to just a year earlier when he had first laid eyes on the big 3,000-ton Norwegian cargo ship Mosdale. She was loading cargo in Montreal harbour for somewhere in England. Later, she would join a convoy of Canadian ships escorted by corvettes and destroyers of the Royal Canadian Navy. The Mosdale was part of the Canadian Merchant Navy, a vital lifeline to Europe, manned by merchant sailors that had to be stopped, at all costs, by Germany’s war machine.

Ray also remembered the conversation he had with his father, in which he asked permission to join the merchant navy. “Absolutely not,” Fletcher Wade had yelled. “It’ll take a catastrophe to separate this family!”

“But Dad, we are facing a catastrophe. We’re at war.”

That afternoon, 16-year-old Fletcher Ray Wade Jr., too young for the armed forces, signed on the Mosdale and sailed from the sheltered harbour of Montreal into the most dangerous waters in the world.

The Mosdale, unlike many of the freighters that put to sea, was a good, clean ship, well run, and with a crew like family. The Norwegians were friendly and Wade soon became quite fluent in their language. Norway and the Netherlands had great merchant fleets all around the globe. Most of these ships had been at sea when Hitler and his Nazi regime had overrun their home ports.

Wade paused and looked out again at the cold, grey swells. Here, on the starboard flank of the convoy, the view was clear; nothing but empty sea and sky. Then, something in the sea grabbed his attention.

Blinking and swallowing hard, Wade couldn’t believe it. Coming right at him, almost abeam and coming fast, was the unmistakable shape of a speeding torpedo.

His mind racing, Wade knew it was already too late! “Oh my God,” he gasped out loud. “I’m dead – we all are!” And, gripping the rail, he braced himself.

He had seen it before, on other ships, in previous convoys. The loud impact, and then the ship would fold right up and shrouded in heavy, black smoke, be gone in an instant. No one stood a chance. “What should I do . . . ” he thought. “Jump? Or should I just let go? Which is easier? How cold is that water? My lifebelt!”

Too late – his mind froze and stopped like a watch. In that same instant – nothing. Then all hell broke loose as the deafening explosion plugged Wade’s eardrums and was followed by the vibrations felt through every nerve ending of every fibre of his body.

But the deck didn’t rise. The ship didn’t fold up, capsize, or even list over. “Dear God,” Wade said out loud. “It wasn’t us!”

And then he heard the ringing of bells followed by the confusion as men shouted orders while hatches and doors slammed shut above and below. Every ship in the convoy rang for full ahead and instantly altered course as many as 60 degrees or more – in every direction.

The enemy torpedo had passed directly under the Mosdale, probably by inches, and hit the heavier ship directly beside them on their port side (probably about 1000 yards away). The escort corvettes and destroyers immediately went into action, running full ahead, heeling over as they turned sharply and piercing the eardrums further as they dropped their depth charges in concentric circles around the convoy. Wade already knew the fate of the crew – those who survived – as he gripped the rail and stared over the stern, beyond the boiling wake, at the funeral pyre of fire and smoke. Men in the black water with blackened faces, choking on oil and seawater, unable to cry out, had very little chance of being rescued. Those ships that were trailing astern might drop scramble nets but they wouldn’t stop. To stop was certain death. Torpedo tubes were already reloaded and waiting just under the surface.

The hapless ship, a tanker as it turned out, was already gone. Tankers loaded deep, with their decks almost awash, and they were a little slower. In the confusion of the black, oily smoke, the burning fires on the water, and the exploding depth charges, Wade quickly ran to his muster station to help ready the lifeboats. Less than a minute had passed if he looked at his watch.

. . . . . . .

During the Second World War, Canadian merchant seamen, many from the Great Lakes area, served around the world, but most sailed the North Atlantic, taking supplies from Canadian ports, especially Halifax and Sydney, to Britain. One 10,000-ton cargo ship could carry: enough flour, cheese, bacon, ham, canned and dried foods to feed 225,000 people for a week; 2,150 tonnes of steel or other war metals; enough carriers, trucks, and motorcycles to equip an infantry division; enough bombs to load 950 medium bombers; and enough lumber, plywood, wallboard, and nails to build a row of dwellings nine blocks long.

In 1942, the Battle of the Atlantic entered Canadian waters when U-boats sank ships even in the Gulf of St. Lawrence. Some 20,000 Canadian and Newfoundland merchant seamen, members of the Canadian Merchant Navy, faced not only enemy action but the extreme and hostile environment of the sea, to deliver soldiers and supplies to war zones around the world. The North Atlantic in wintertime could be more hostile than any submerged U-boat lying in wait. Some 1,629 Canadian merchant mariners, including eight women, sacrificed their lives. In all, 85,775 Allied ships sailed in 2,889 escorted convoys to and from the United Kingdom during the war. A total of 654 ships in convoy were sunk – warships excluded – and 1,578 other merchant ships were sunk while sailing alone. A total of 11,899,732 tons of shipping was lost.

The human loss is staggering. Besides the 1,629 Canadians killed, at least 30,000 British mariners were lost, as well as 5,662 Americans and approximately 4, 800 Norwegians, 2,000 Greeks, 1,900 Dutch, 1,900 Danes, 900 Belgians, and as many as 6,000 seamen from neutral countries. “It was the merchant seamen who suffered most,” Royal Canadian Navy corvette commanding officer Alan Easton wrote later. “They could not really fight back or even manoeuvre quickly to avoid attack. They presented the best targets and never knew when they would be singled out for extinction. The suspense must have been awful . . . we Navy men did not go through the torments they did, nor did the other fighting services. A merchant seaman could fortify himself with nothing but hope and courage.”

May 1, 2022. We’re at the Naval & Merchant Marine Memorial at the Marine Museum of the Great Lakes, in Kingston. Ray and Lillian Wade are not here anymore, having passed away some years ago. Surrounded by cadets from the Royal Military College, presided over by the RMC Commandant, Commodore Josée Kurtz, Major Stewart and I straighten up from laying our wreath with others, salute, and turn sharply to the right. We return to our seats. Thoughts of Ray’s story and his notes from his wartime diary came flooding back to me.

Young Raymond Wade and many others survived those convoys. Survived, married, and had families of their own. But they would relive those dangerous trips night after night in their dreams for the rest of their lives.

Shortly after, standing to attention, a bugle sounds the last post. Then silence.

By Brian Johnson

Former Captain, Wolfe Islander III and Former Naval Reservist, HMCS Cataraqui, 1972-74

Brian Paul Johnson was one of five captains of the Wolfe Island car ferry Wolfe Islander III. He worked for the Ontario Ministry of Transportation for more than 30 years, recently celebrating 20+ years as captain. He also recently retired as a captain of the Canadian Empress.

Click here and here to see many of Brian’s contributions!

Posted in: Volume 17, Issue 5, May 2022, History, People, Places

Please click here if you are unable to post your comment.