Island Winter

by: Glenn Sandiford

People who hear that I spent my winter on an island in upstate New York typically have one of three responses. They're envious; they couldn't do it because they'd feel lonely; or ask, with dismissive incredulity, “Why would you freeze your ass off wintering in the Thousand Islands?”

I spent this past winter at my boathouse cottage on an island between Clayton and Alexandria Bay. During summer, I share the island with eighty-plus families, who blend into a lively community where neighborliness counts far more than income-level. Splashing children are monitored by multiple eyes, stalled boats drift only minutes before help arrives. I bought my little place three winters ago, and since then my social life has never been busier.

Come September, however, most folk return to lives elsewhere, often out-of-state. By October, only a handful of diehards remain, and Thanksgiving finds the island all my own.

My first year I had stayed until December 16th, then January 17th the following year, and didn't return until mid-March. My cottage, though insulated, was nowhere ready for a winter stay. Neither was I. But last fall, after another round of renovations and ready to resume a book project, I began serious consideration to overwintering here. No-one had done that on the island since the 1950s.

Cold was not the issue. My small second-floor home is easily warmed with two portable radiators and a propane heater. The challenge was the River's transition from open water to ice, and whether the ice would thicken enough for walking.

My boat is only a 14-footer. I can raise and store it unaided in my boathouse, rather than being dependent on a marina. Mildish weather allowed me to continue using it through Christmas and into the New Year. Finally, on January 14th, after one final trip for provisions and with an arctic blast in the forecast, I pulled my boat from the water. Kayak was my only remaining avenue to the mainland.

Two days later, the River was covered with thin ice, and I was adjusting to winter on an island.

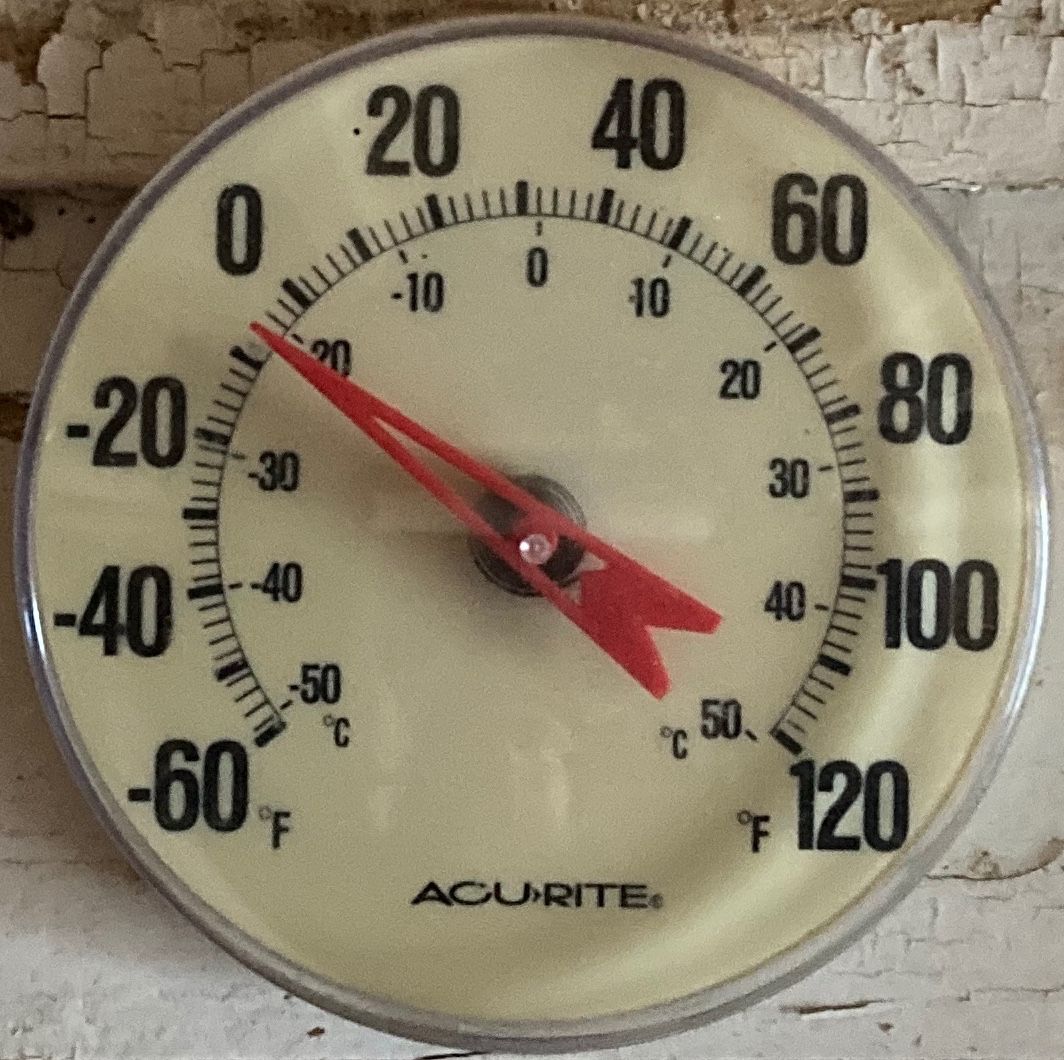

I likely would have already fled had I known beforehand it was going to be a La Nina winter, with wind chills approaching -30°F some nights. But as a deep freeze took hold, I realized the first of several upsides. The ice thickened quick, and thickened deep. Six inches, then twelve, until strong enough to bear a car — or lone human with a dog.

Gyp and I had a wonderful time walking on water. Twice daily loops around our island, animal tracking, 2-hr treks around nearby Murray Isle for a view of distant Canada, spectacular and ever-changing winter scenery. And hauling provisions by sled from Wellesley Island, connected to the mainland by bridge and where I'd temporarily parked my car.

In winter, the landscape transforms into snowy desert sculpted by cold and wind. Islands seem to shrink, the River widens. Vast ice-sheets flex like a tectonic plate, their momentary shivers rippling under your boots. One feels tiny, insignificant, humbled by the scale and beauty of it all.

My collie-mix companion possibly loved the winter even more than I, despite being almost 17 years old. Unlimited ice-pack to roam, animal sign galore, warm heater afterward. Like a sommelier with wine glass, Gyp would plunge his nose into tracks, absorbing the scent and instantly ascertaining its freshness (and looking clownish with snow-covered snout). His eyes and ears are rather less acute. When he spotted his first snowmobile, speeding upriver, he mistook it for an animal and raced after it for a quarter-mile, until losing sight of it (and I was losing sight of him . . .).

Was the winter cold? On some days, hell, yes. I tried to continue renovations, but by late January my fingers had deep cracks that constantly throbbed and bled. A neighbor told me about finger protectors, basically a condom for digits, but they tore unless I ceased manual labor. The cold hindered photography too. As soon as I removed my gloves to operate my phone camera, I had thirty seconds before my fingertips froze and became unrecognizable to the touch-screen.

Worst was the cold floor. Living directly above my boat slips means a lovely viewing perch — but when water turns to ice and sub-zero winds are whipping under the boathouse doors, the view isn't so enjoyable because your feet are numb despite slippers and two pairs of socks. When writing at my desk I had to wrap my legs in a sleeping bag. Eventually I erected a temporary door to separate my front room from the bedrooms, reducing my living space to 350 square feet. Problem solved. I switched off my propane heater, set the two radiators to 70 degrees, and wrote, cooked, and slept in comfort.

Winter wildlife was plentiful, and mostly observable from my desk, which looked across a wide expanse of ice toward Murray Isle. With all but one human gone, the local fauna felt less need to conceal themselves. Most prominent was our island's resident pair of foxes, Short-Tail and Full-Tail. The ice expanded their territory ten-fold, such that their hunting became a daily circuit of multiple islands.

Mink and bald eagle were constantly active. One strange morning, a mink scurried across the ice to within thirty yards of Murray Isle, whereupon another mink raced from Murray to meet it. They briefly wrestled, then separated and vanished in different directions, moving so fast I couldn’t keep up with my binoculars.

A coyote once strolled past, two hundred yards away on the open ice, his confident demeanor as top predator strikingly different to the skittish foxes. Three deer from Murray wandered here for an overnight browse before departing (thankfully). Most thrilling of all, a pair of otters spent thirty minutes diving and feeding at an ice hole, until bombed by a bald eagle. An hour later, Full-Tail was there checking for scraps.

I would have investigated too, only strong winds had recently broken apart the ice there, and in the main River, too. The Big Breakup occurred one night in mid-February. Forecasters had predicted a mild month, so I was excited. Alas, all open water was frozen again within days, except the new ice never thickened more than two or three inches. Strong enough for fox, but I didn't dare test it. Fortunately, the much thicker ice off Wellesley remained solid and I managed a couple more treks for provisions.

Obviously, winter on an island entails danger. So does flying six miles high in a plane, or boating off Alexandria Bay on the Fourth of July. We make our choices. “The only person not worried about Glenn, is Glenn,” an island friend had said in December when word first spread about me possibly staying through winter. She was only half-joking. And I did worry some days.

My island is not remote. Wellesley is only a half-mile away, swimmable in summer. Nonetheless, the water makes all the difference, physically, logistically, psychologically. Without it, this island would simply be just another hill.

Winter heightens the feeling of separation. Morning and evening, at the mid-point of my walks with Gyp, I would pause to look across the frozen water toward Wellesley. The ice was both lifeline and life-threatening. It looked consistent, and friendly ice-fishermen assured me it was a foot thick — but other locals warned of treacherous weak spots created by underwater springs and currents.

Falling through the ice was always my biggest concern. At the same time, an island winter without ice-walking would have felt incomplete. And I needed groceries.

Weather permitting, I timed my provision runs for days when ice-fishermen were out, hoping they would notice if an accident happened. Gyp trailed a 25-foot rope that I could grab if he took an unwanted dip. He and I always wore life-jackets, and I carried a hand-ax with which to haul myself back onto solid ice.

That said, I knew a life-jacket in winter would most likely serve only as body preserver. If I plunged through the ice into deep water, I would have only a couple of minutes to save myself, and almost certainly be alone.

Gyp was my sole company for the winter. Passersby were few, and mostly unaware of my presence. Perhaps a dozen snowmobilers, three skiers and two snowshoers, a family hiking. Plus two iceboats, one being the Clayton Rescue Squad.

The solitude was precious. Equally, though, I never felt lonely. Rare was the day without at least one call, text, or email checking my safety and sanity. There was also mail, care packages, and even an occasional brief visit. One person dared to spend a night at his own cottage.

I was happy to see my neighbor — and not unhappy when next morning he returned to the mainland. I wasn't quite ready for Glenn's Winter Kingdom to revert to cottage colony.

Even so, my island winter was a group experience. A whole team seemed behind me, islander and mainlander alike, variously monitoring, advising, teasing, and helping from afar — and ready at a moment's notice to call friends who owned a snowmobile or airboat. One such person was Zach Russell, fearless young caretaker on nearby Wintergreen Island. Even he (reluctantly) winters on the mainland. But it was his early enthusiasm about me possibly wintering here that had finally convinced me to attempt it, and he subsequently kept an eye on me by snowmobile.

Among my neighbors, Ben Smith of Rochester shipped two surprise boxes of goodies from Trader Joe's, the chocolate alone surpassing F30,000 calories (yes, I counted). Syracusan Mike McMahon parked his car at Wellesley to watch my first ice-walk, ready to call 911. Thereafter, requesting that I wave daily at his house camera, he periodically left milk, bananas, and even a roast chicken for me to collect at my convenience, and sent constant advice and insults.

The winter proved to be as much about friendship as seclusion.

By Valentine's Day, cabin fever was bubbling. Friends now showed a darker side, forwarding weather updates from their winter homes in the balmy South. Mike and his wife Mirian, vacationing in Florida, sent beach photos. I built a snowman, but felt more was needed to defend my Thousand Islands winter. So one sunny day, with temperatures in the mid-twenties, I put on swim shorts and a tank top, grabbed a sun lounger, and walked to the McMahons' ice-encased dock, knowing my movement would trigger their camera. Gyp was mystified. I laid a towel on the thick ice, crouched as if to dive, and launched myself into a chest slide across the ice. After mimicking a few swim strokes, I toweled off, grabbed a book and sunglasses, and sunbathed in my chair . . . until my toes turned white, which took about five minutes.

Unfortunately, my prank failed. I was too far from Mike's camera to trigger it. No matter, most of my winter was unseen by all but me.

Warmth finally came third week in March. The Big Melt took only six days to clear the main River, while ice in sheltered areas fractured into huge slabs. On the seventh day, I checked the view toward Wellesley. My ice-walking days were done. Waterfowl swam in patches of open water, ever-shrinking floes were stained with goose poop. As I watched a pair of swans feeding upside down, as if mooning me, movement caught my eye. It was Short-Tail, trotting across slushy ice between two one-house islands. Suddenly the ice gave way. Fox plunged into frigid water, momentarily submerged before clambering onto solid ice and hurrying back to safety, bedraggled and startled in equal measure.

Not many people can say they witnessed such a moment on their sixtieth birthday. Or any day, for that matter.

Winter's over, I announced to my island community. Gyp and I had survived, and we needed only a haircut to resume public life. He resembled a shaggy bear cub, whereas I looked like a scruffy hermit. Amidst the celebratory replies and threatened intervention for a psych evaluation, a couple of people asked if I'd do it again.

Absolutely I would.

As for what I learned about myself, nothing much new, other than my blood perhaps contains a little more anti-freeze than is normal. I know myself well enough. However, much was reaffirmed, about resilience and resourcefulness, minimalism, nature and solitude as medicine. We all need affirmation sometimes, especially after loss or trauma.

Still, that wasn‘t the primary intent of my island winter. I chose to freeze my ass off wintering in the Thousand Islands because it was magnificent adventure.

by Glenn Sandiford

Glenn Sandiford began his career as an environment journalist in the Adirondacks, then taught in academia for more than two decades, specializing in environmental communication. He now lives in the Thousand Islands.

Editor's Note: Glenn Sandiford has given us the gift of winter island life, without the need to get cold. It is written in the author's voice with no edits and is longer than regular articles.

When I first started my adventure with TI Life in the winter of 2008, Ian Coristine wrote to me one day and said. "Susie, see if Dick Withington will share his winter island living story with us." I was not all that keen - heck, it was an essay, not history, and maybe readers would not be interested. Ha! Dick's "A Winter Islander, followed by Winter Island Living, "How do you do it?"... are two of our most-read articles. So, I express the appreciation of today's TI Life readers in thanking Glenn Sandiford for being as he says a "winter resident."