Halloween Storm of 2019: A Witches’ Brew First-Hand*

by: Raymond S. Pfeiffer

To know that a storm is coming is to apprehend mystery and fate. My dear friend, JBJ, and I had begun Halloween morning watching patches of fog and rain on a dark, unusual, completely still River. She thinks of the fog moving up from the water as witches rising. It is an apt thought in light of the fury that was forecast to come later.

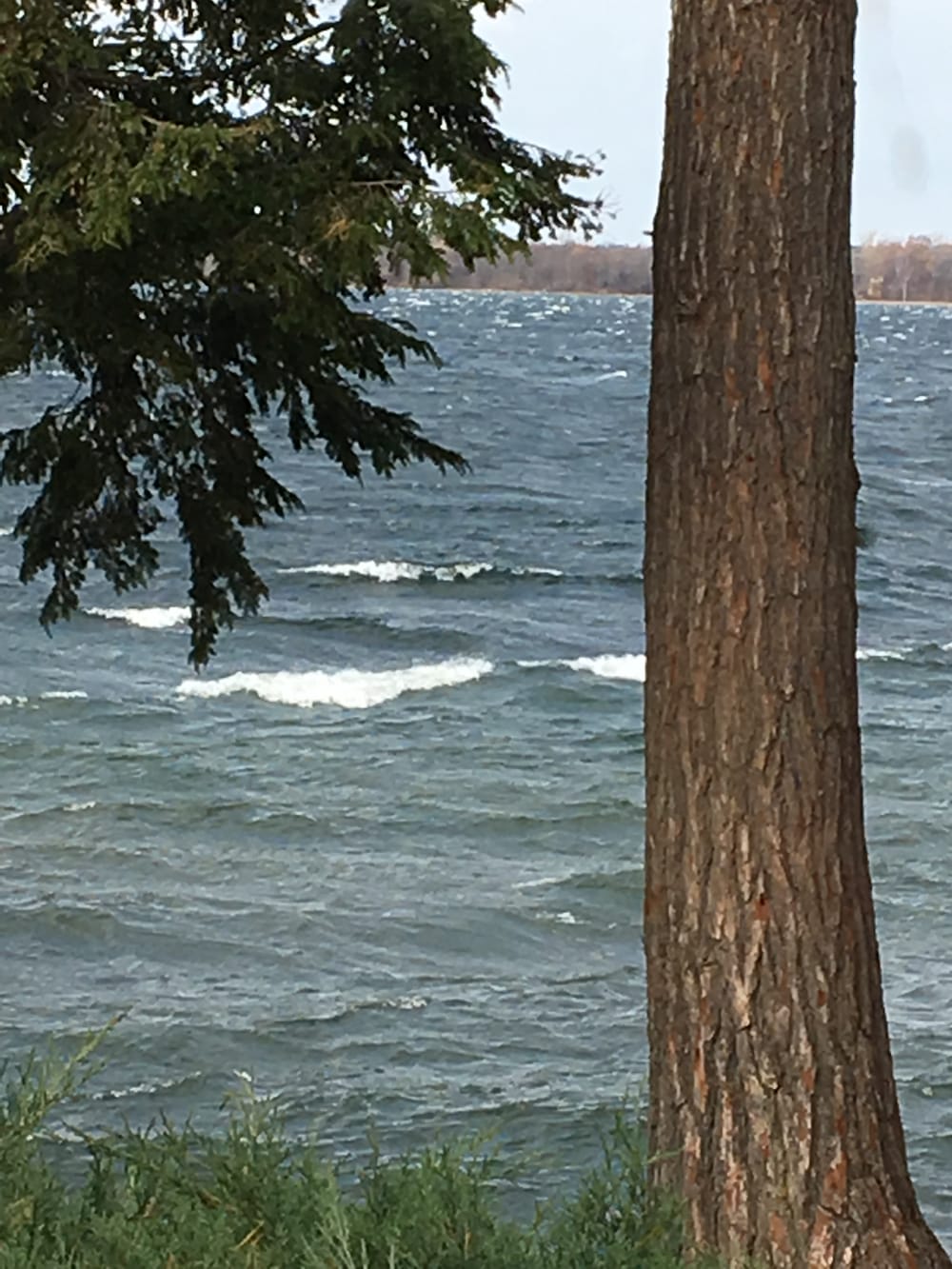

Throughout the day, we could feel deeply the changing River moods, while inside our small house on the little island at the head of the Lake Fleet Group. In the afternoon came more rain as the atmospheric pressure dropped further. A westerly wind started mid-day, and it continued, strengthening during the afternoon. By bedtime, it was blowing a gale.

Strong southwest winds had been forecast for the day, with gusts on Lake Ontario supposed to exceed 100 kilometers per hour. JBJ was a little worried, but I was not, as westerly winds are not generally a problem on The Punts Islands. When going to town, we have several possible routes, one through the Forty Acres, and one avoiding them. I usually enjoy riding the big ones on the Forty Acres. As a child, my mother would not allow me to ride on roller coasters. My sympathies for big waves derive from my childhood thrills of rowing our old punt through them, shipping water, and then heading back as the water surged about in the boat. I mostly love a good storm!

By bedtime, the storm had become extreme. The wind was more than howling, JBJ said it sounded like a freight train thundering through the trees. After a while, I dozed off but was awakened at about one in the morning by the ongoing roar all around us.

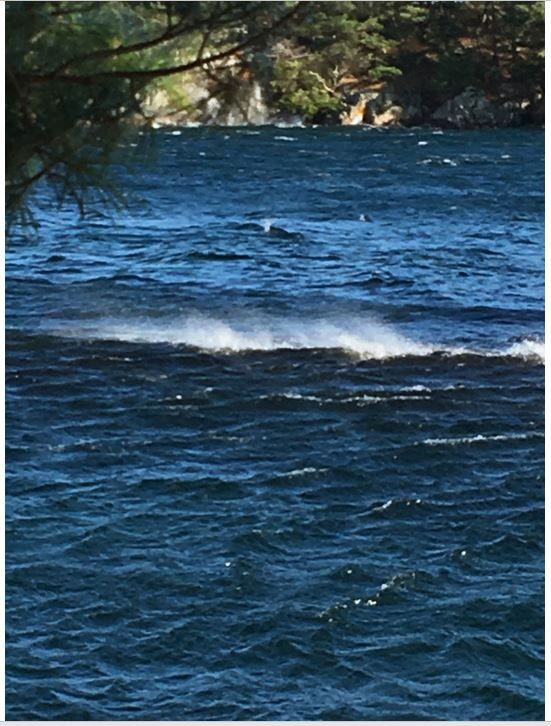

I walked out to the living room and shined a light on the little harbor between the upper docks. I was struck by what I saw. Our nineteen-foot Grady-White, the Grape-Nut Two, was not only banging hard against the dock, but rising up and down in swells like I had never seen in this protected little channel. The waves were on top of the swells, and rose up as secondary to huge rises in the water beneath. It was like the ocean, and I felt fear in my bones about the boat and even the docks.

We both dressed quickly, and walked carefully down to the docks, where boiling, riling, opaque water was surging all around us. It had clearly risen over a foot since dinner. Our boat was heaving against its tie lines as if determined to break free. Uncertainty shook us then, and we were unsure that we could do enough to resist the forces of nature that had built up so wildly all about us.

Carefully, and with difficulty, we fastened a harness to the port side, slinging the boat off of the middle dock and tying it to the upper dock, some twenty feet up-stream and up-wind to the west. The temperature did not dip below eight degrees Celsius, (forty-eight degrees Fahrenheit) all night, so at least the spray was not freezing where it landed and the ropes were easily tied and re-tied.

Back in bed, I felt serious worry that our boat might not make it through the night. Having done all that I could, I dozed off, although JBJ could not sleep. She had even put a pillow over her head to try to deaden the drone of the roaring wind. Then, something awakened me again at three, as there had been no weakening of the roar.

Dressed again, and both of us down at the dock, JBJ walked out and discovered that she could possibly be blown off, and scrambled to hold on. I felt destabilized by the wind at one point as I leaned over to tend a line, my feet washed by the caps of the waves coming over the upper dock. The swells coming and going more than ever, we saw that the boat’s stern line was frayed and about to break. We then secured additional lines at all points, hoping we had done enough.

Back in the house, the electricity still on, we were too worried to read online about the storm. The extremes of the storm were brought by a classic Lake Ontario differential of pressure. The atmospheric pressure on the west end of the lake was high while that on the east end was low. This souped up the wind and created a classic seiche, or surge in the Lake, driving a huge amount of water to the East end and squeezing it into the River. That surge came in stages, the first of which we had experienced earlier in the night. But the second was more extreme, and came sometime after our second time at the dock.

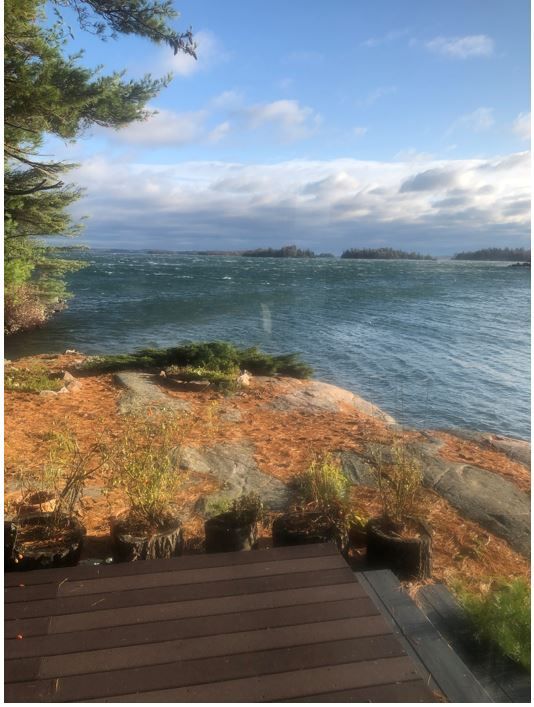

At dawn, the power was off. The wind was ferocious, and not far from its peak. There were now breaks in the clouds, which added color and a feeling of warmth to the island and that wild water. We walked quickly to the dock to see what had happened. Everywhere were marks of water that had risen two more feet since three o’clock, but had declined around dawn. Yet, we felt relief that the boat had survived the most extreme wind, waves and water surges that I had ever seen.

There were piles of debris on top of the docks in several places, amounting to nearly a cubic meter of flotsam in each spot! The water had gone up over the docks, rising a full three feet from its level at mid-day on Halloween. The boat bumpers that normally hang on the dock were all up on top of it, blown by the high water and waves. The bumpers tied to the boat had helped save it from damage. The original, old stern line had, however, been broken by the storm. It was clear that the boat had been saved by the extra stern line, the Andress-design catwalk with its sturdy upright posts, and the harness and line attaching the boat to the upper dock.** Had the catwalk and the rope from the upper dock not been there, the boat would have been up on top of the middle dock, if not smashed against the rocks.

Inside the boathouse room was a line showing where the water had risen. It was as high as it had been on the third of June, the apogee of the highest water in recorded history. Outside the boathouse room, even the big rocks and heavy cement blocks I had piled on the dock had been moved by the waves in high water. I had never even thought of such a thing!

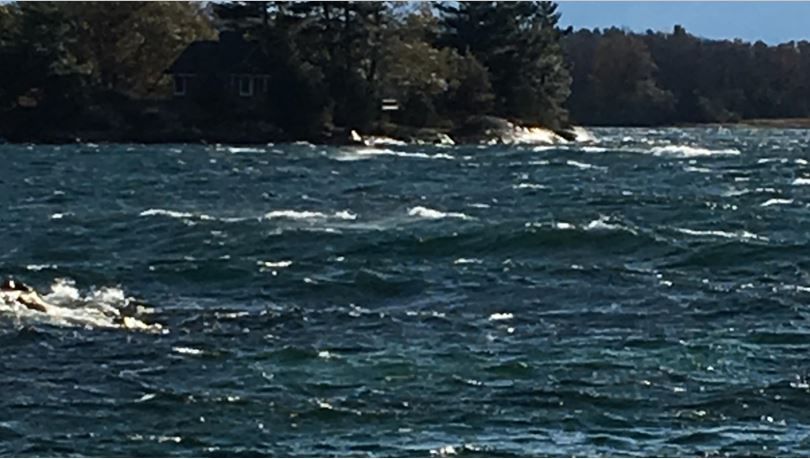

The wind began to soften in the mid-morning, which was important for our plans to leave the island to attend a birthday party in Cobourg, ON. JBJ had been afraid to go out on such wild water, and I had no intent to take excessive risks or cause more fear than necessary. After breakfast, I had little doubt that we could make the trip to town without incident. The course going a little down-wind and below Hay Island looked to be a relatively easy ride, sheltered from the small mountains of water out on the Forty Acres.

In mid-morning, we packed up and headed out, encouraged by breaks in the clouds and occasional sun. We bobbed our way to Gan, washed by heavy spray against our windshield and top, worrying JBJ some, but crossing with no real trouble. The waves right off our lighthouse were over two feet high, and the current was moving fast. I felt confident that I had tested out the Grape-Nut Two in former storms to see what she could do. I knew her limits well, and knew that we were taking a course in which we were not seriously challenged.

Approaching the opening to the Gananoque Marina, we could see a big and unique boat coming down the channel from Howe Island. She went into the marina before we arrived, and I could see that she was an Ontario Provincial Police patrol boat of an older model, with a metal hull of perhaps eleven meters long, and not one of the more recent faux inflatable types. I thought that the police might stop us, as I believed, but had not actually seen, that there were surely storm warnings out for small boats everywhere on the River. We did not see another boat on the River that day! As we unloaded at JBJ’s slip, the police boat ambled about inside the marina. I believe that she was dispatched from Kingston to patrol the Gananoque waters and marina, and to keep people off the water, in order to protect public safety.

Discussions with Hydro One workers in their trucks at the marina revealed that downed trees on Lake Fleet Islands below us were the likely cause of the power outage. Our need to leave the island in the morning gave us no time to take any steps to power up the refrigerator. We had not opened it in the morning before we left, hoping to preserve its inner coolness as long as possible.

Upon returning Sunday, most of the refrigerator contents were still cool when we could connect our little camp generator, and lower the temperature further. The power came back on by Monday afternoon, and we soon had water pressure in the pipes again. The fact that the temperature never dipped below freezing had saved the outdoor plumbing.

In the end, we had escaped damage to our trees, boat, docks, plumbing, much of the food, and best of all, ourselves. It was a storm that had broken loose many floating docks all up and down the River, set a floating boathouse adrift, and done extensive damage to other docks and boathouses on islands as well as on the mainland shores. The River had shown the power of its elements in extreme circumstances. It had been the most fearsome and dangerous high water event I had ever seen in almost three quarters of a century, surpassing even the storm of early May, in 2018. How fortunate that this storm occurred while the water was about three feet below its highest level on June the third of this year!

*The author is especially grateful for the help of Judith Bedford-Jones and Rheal Dupuis in writing and illustrating the story.

**The catwalk design originated from the Hickory Island caretaker, Jack Andress, in the early 1950s.

By Raymond Pfeiffer, The Punts, Lake Fleet

Raymond Pfeiffer is a Professor of Philosophy, Emeritus, from Delta College in Michigan, author of three books and twenty scholarly articles. He is a lifelong River Rat, occupant and caretaker of The Punts Islands, a long-time sailor and maintainer of St. Lawrence skiffs, a fisherman and boater who has lived on Hickory Island, Grindstone Island, and The Punts.