Episode 2: How Roscoe Fish Got His Name (Part l)

by: Sarah Bodine

[Note: See Introduction: Roscoe Fish Stories, January 2024, and Episode I]

Warm Currents, Cool Currents

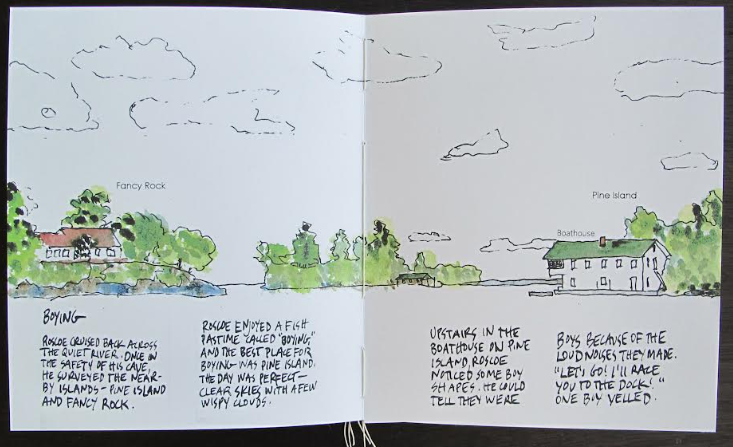

Roscoe spent so much time at the Frost Diner that it became his home away from home.

He even began to help Percy with the daily menus. Fish are voracious. They are always scavenging for food . . . from Great Northern Pike, who’ll eat just about anything, to the little Yellow Perch, who are picky, delicate eaters, venturing out only at dawn and dusk, to nibble on tiny aquatic insect larva. So, the popular diner required nonstop foraging, both in the water and on shore. Fish usually move around the River, looking for food in the shallows or depths, depending on the seasonal water temperature.

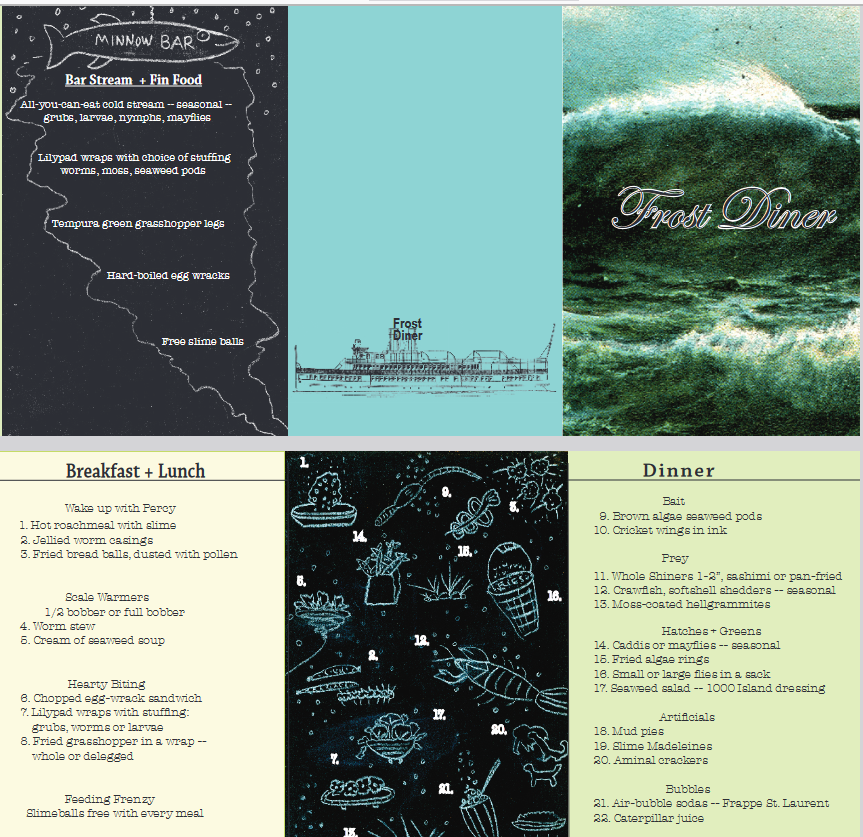

To help Percy make his menus match the seasons, and lure fish to the diner, Roscoe discovered a useful instrument called a deptherm. He found one by accident one day, while he was zooming along the river bottom. All of a sudden, out of the corner of his eye, he noticed a shiny cylindrical object attached to a string drifting down in front of him. Since it didn’t look like the worms that often dangled near his cave, he stopped and gingerly tapped it with his fin. It didn’t bite or sting, and it came to rest motionless on bottom. Seeing that it was harmless, he whacked it with his tail fin, grabbed the string in his mouth and dragged it back to his cave. After some study, Roscoe realized that this was a precise temperature-prediction tool.

In summer, as it registered warmer water, he could tell when fish would be heading to the shallows. And in the fall, as the water grew chilly once more, he knew when everybody would be migrating to warmer quarters before frigid temperatures made the River impassable. So, on a daily basis, as he headed out for the diner, Roscoe tucked the deptherm under his fin. He would measure the water temperature when he got to the diner in order to tell Percy when the wave currents were the ideal 67 or 68 degrees. Then Percy would know that fish would be more active, and that meant he would need to load up on supplies.

The Diner Crew

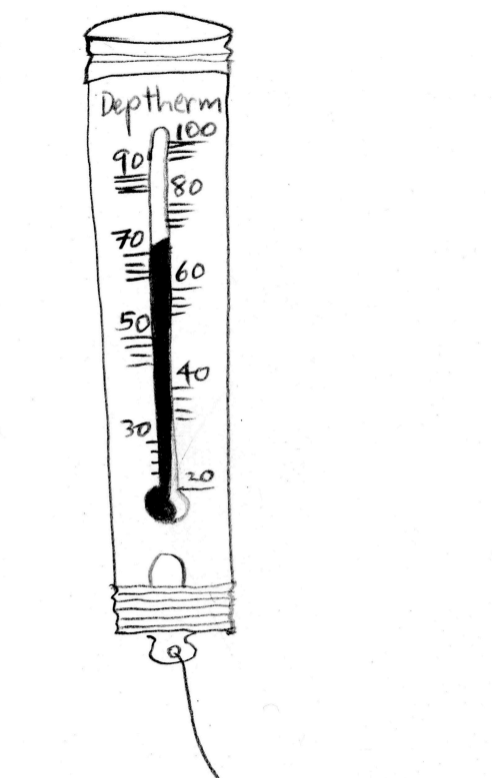

Percy needed a wide range of suppliers to fill the diner’s cupboards daily. Besides the eels who collected insect larva, Percy found turtles to gather seaweed in the shallows. During the day, turtle youngsters would climb up on old logs and hang out in the sun. They watched for boats to go by, churning up the seaweed with their propellers, making it easier to harvest. They marked these places for the big snapping turtles who gathered up the short lengths of seaweed at night and swam with them piled high on their shells over to the box turtles. The box turtles then packed up the seaweed and pushed the floating boxes across to the diner. Because the turtles couldn’t dive all the way down to the ship’s hull, Elver, the eel son, waited near the surface to accept the delivery. As the turtles submerged the boxes one at a time with their clawed feet, Elver elongated his body like a conveyor belt to let them slide down to the diner’s pantry.

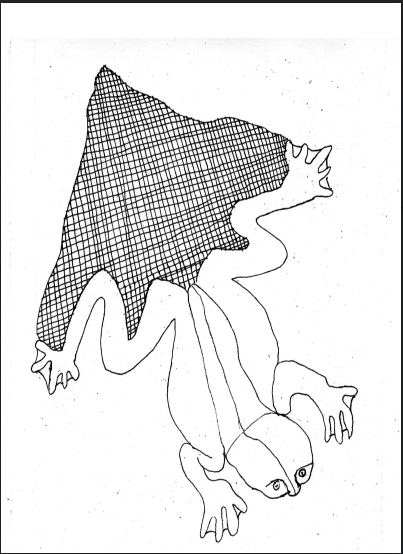

Percy found that frogs of all varieties were willing to forage for food supplies. This was dangerous work, because large-mouth bass like to eat frog as a dinner entree. So, because bass tend to sleep at midday, the frog crew worked the lunch shift. There were many frog types, each specializing in a particular diner menu item. For example, the largest members – the big bullfrogs – lived in the vegetation near the water’s edge, where broken-light patterns helped camouflage them. Here they set up holding pens for large insects, like grasshoppers and crickets, as well as for crayfish and minnows, and occasionally grubs. Medium-sized mink frogs harvested water-lily pads. They tested the pads by climbing up on them. If a pad gave way under their weight, it was tender enough to harvest for the diner’s popular lily-pad wraps. Green leopard frogs acted as guards, making sounds like plucked banjo strings to let the other frogs know how much food they had on hand and where to find a nearby drop-off location. Holding pens for the harvest had to be moved daily, because foraging fish often tried to raid them.

Hundreds of little spring-peeper tree frogs worked the canopy for flies that hatched out of the water and swarmed tree branches. After trapping clouds of flies, tree frogs transported them down to the storage pens in lightweight spider-web sacks secured between their wide toe pads. With all of these reliable suppliers, Percy usually had a wide variety of fresh food on hand to serve the diner patrons.

Rose

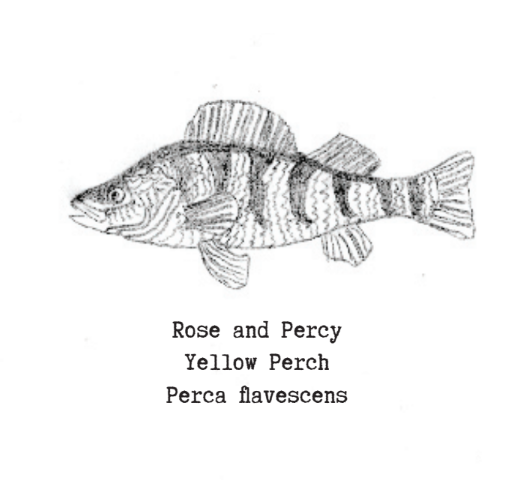

One fine June morning at breakfast-time, Roscoe arrived to find the diner’s deep entry hatch fully open, which allowed fish to swim freely in and out. If the deptherm had predicted a cold front was approaching, or Percy expected hot river currents, he would pull the hatch shut to keep the water temperature inside neutral for as long as possible. On this beautiful day, however, the hatch was wide open, and the diner was crowded. Roscoe scanned the hull, checking to see who was there and looking for his friend Rose. Rose was an energetic perch, and it was no surprise that she had landed a job at the diner as a waitress. It turned out that she was distantly related to Percy. And also, Roscoe had given her a fins-up recommendation, as they were best friends, because many years before, they had been traveling companions on a great journey to find their home in the St Lawrence River.

Rose worked the bustling and boisterous breakfast rush by spinning around the diner like a striped top – taking orders, refilling slime-ball baskets, and sifting pollen on top of roach-meal bowls as they arrived from the galley kitchen.

Roscoe claimed his favorite spot on the corner rock stool and checked the slate board specials. Feeling hungry, he ordered a large, steaming bowl of jellied worm casings with green-seaweed syrup. As he waited for his breakfast, he noticed a family of catfish lying at the bottom of a nearby booth. The youngsters twitched in delight as Rose rolled slime balls at them along the narrow planks of the ship’s deck. Seeing Rose happily at work, Roscoe fell into a reverie – his mind wandered back to his youth and the memory of how he and Rose had met.

The Legend of Roscoe’s Birth

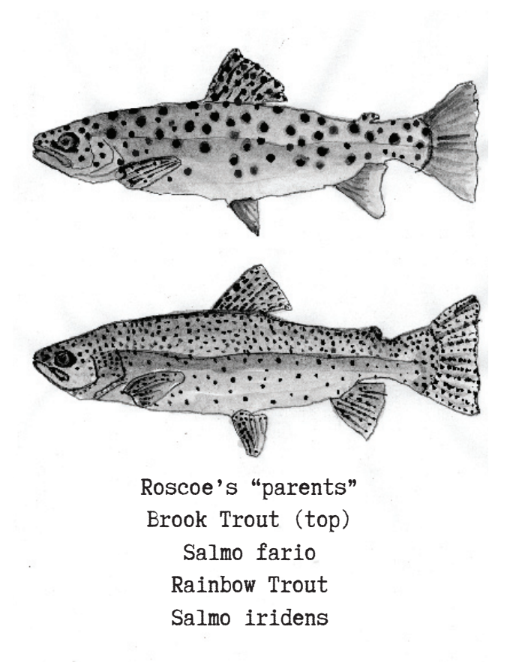

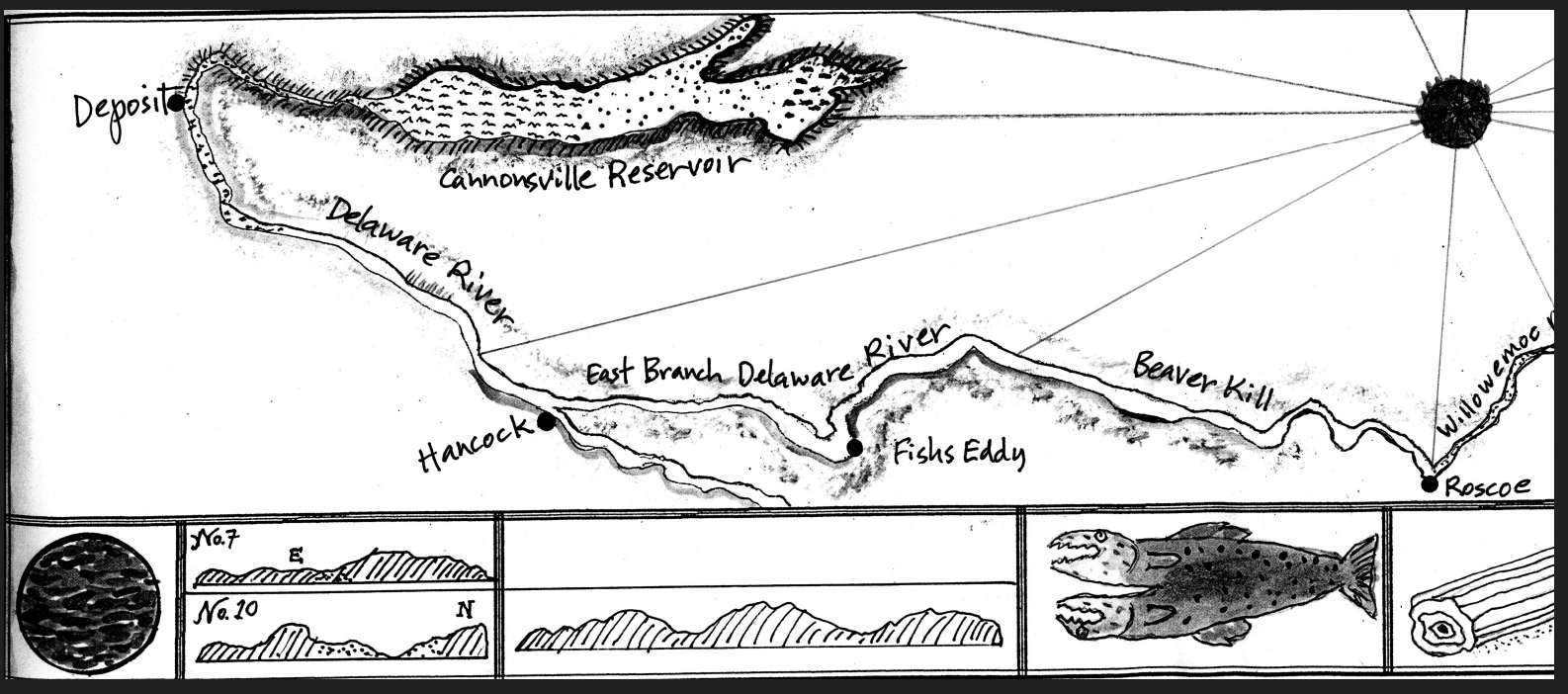

Roscoe’s story began in a place far away from the Thousand Islands. His parents were not St Lawrence River fish at all. He was spawned in the pristine waters of the Willowemoc River in upper New York State, near Trout Town, USA. The Willowemoc is a pretty, meandering river that runs through the Catskill Mountain State Forest Preserve. This river has been a trout paradise for generations. In fact, for many years, Roscoe thought that his father was a native brown trout and his mother a shimmering rainbow trout. He could still picture his mother’s iridescent skin glistening in the sun whenever she rose to snatch a nymph just below the crystal-clear river’s surface.

Up in the icy mountains where the river waters originated was the spawning ground for trout families. Each year, during the first heavy rains of autumn, Roscoe’s parents would join the throngs who made the difficult journey upstream. His mother would choose a deep gravel bed to lay her eggs that would hatch some of the thousands of youngsters during the next season.

The year that Roscoe was born, however, everything changed. As usual, his parents had gone upstream beyond the Willowemoc, into the East Branch of the Delaware River, to make a nest, lay eggs, and wait until spring for the hatch. All went well, although his mother had caught a slight cold during the winter. By the time the warm sun had melted the ice from the stream once again, and the water reached 50 degrees, she felt well enough to join the new trout families as they began to make their way downstream. Her illness had slowed her down somewhat, but she was happy to hang back behind the hoards of small fry, checking to make sure that everyone found enough to eat along the way.

After a time, she began to notice something curious. One of her brood didn’t look like the other fingerlings. His skin was rougher, scalier, and his body shorter and more compact than that of his brothers and sisters. Further, he did not dart around at lightning speed like the others, but seemed to dawdle and, to her dismay, sometimes to swim near the surface of the water. She also noticed that the tiny fins along his back were spaced irregularly, and he was growing an extra, spiny half-moon fin that jutted out in a dozen sharp points.

During the course of the journey, she cautiously pointed this out to his father, who confessed that he was surprised that this little one’s gills were irregularly shaped. Also, he had begun to wonder why the youngster wasn’t developing the beautiful red spots on his sides like a brown trout, nor the multicolored hues of a rainbow. In fact, the skin on his back was mostly bronze, shading to a yellowish green, with dark vertical banding on the sides. And his eyes – his eyes! They were deep red, not at all like the black eyes of trout youngsters. With time, the mother and father began referring to this short-backed offspring as Smallie.

As spring blossomed along the Willowemoc, when the rhododendron and mountain laurel burst into brilliant white and scarlet, Smallie’s brothers and sisters were learning to dart through the water at high speeds using their tails as rudders; diving down into rocky pools and daring each other to snag a nymph before it rose to the surface to hatch into a mayfly. Smallie, however, spent more and more time by himself on the dark bottom or in the deep shade under fallen trees. Sometimes he hung out with the oddball trout with only one fin or with a slight nick in their tail. He began visiting the nursery school playground because he enjoyed entertaining the small fry at recess. They took turns climbing up the scales on his torpedo-shaped body and sliding down his sloping nose, and they delighted in his clown-like antics. He could use his rigid dorsal fin for tricks. Holding two or three small, red-and-white Styrofoam balls –- the ones that littered the stream in the summer –- on his spines, he tossed them one at a time into the air by whacking them with his tail. Then he spun around and, as they hit the water, caught them all at once in his mouth. The small fry clapped their tiny, orange pectoral fins with glee.

One day, in the heat of the summer, when everyone was treading water at the bottom of the stream bed or searching for cooler rills in the tail waters downstream, Smallie disappeared. When he hadn’t been seen for three days, his worried parents began to look for him in the eddies and pools of his favorite haunts. They even sent a search party of five brave brook trout brothers up to the headwaters at the confluence of the Willowemoc and Beaver Kill Rivers, where the ferocious two-headed trout that ate fingerlings was fabled to live. Also, it was the season when some of the best swimmers, even old timers, had disappeared after they rose to bite on the irresistible dry caddis flies that skipped along the water’s surface. These sharp-tailed insects could jab into a trout’s mouth and lift him clear out of the water.

As it turned out, Smallie was so hot and uncomfortable that his head was spinning. He had started upstream in a daze, looking for deeper, cooler waters. His parents had cautioned him against wandering into the treacherous northern waterways alone, but he passed what he thought was a familiar log and took a wrong turn. By nightfall Smallie realized that he was lost. With all the boglike brooks and creeks leading out of the Delaware, he could not find the mouth of his native river.

The next morning, confused, frightened, and hungry, he swam farther and farther. He passed towns with strange names like Fishs Eddy and Deposit. The narrow channel dumped him into a large body of water, which, he found out later, was the Cannonsville Reservoir. Little did he know that he was beginning a long and sometimes dangerous journey into the unknown, where he would make new friends and encounter treacherous enemies. All of the skills Smallie had learned from his trout parents would be put to the test, and more. He was entering a space and time in which he would be free to cultivate his difference from others, and his world would be changed forever. It was now up to him to discover who he was and where he belonged.

Big Water

Although he missed his family, Smallie quickly adapted to life in the deep, wide water of the reservoir. He cruised along the slow currents, nestled into the gravel bottom and tread water under the cool rock ledges. So far, the reservoir seemed deserted. But one day, as he was searching along the shoreline for a snack of crayfish, he came upon something unusual. A hollow tree trunk was bobbing up and down just under the surface of the water. As he swam closer, he saw that the trunk was bursting with mouth-watering worms. It was irresistible. Without thinking, he plunged in. All of a sudden, the trunk started to jiggle and shake. Smallie flipped over, trying to escape, but just then the end of the trunk snapped closed, and everything went dark. This “tree trunk” was, in fact, a large barrel used for collecting and transporting fish. Big trucks with winches hoisted the waterlogged barrels out of the reservoir once a month or so and headed up north to stock lakes for sport fishing.

The truck’s noisy diesel engine clanked into gear, while Smallie squeezed into the far recesses of the barrel. He bumped into lots of other scared fish, their bodies all jiggling about in the darkness. He must have passed out from fear and worry because the next thing he knew there was an eerie silence. The truck engine had stopped rattling. Suddenly, the end of the barrel clanked open, and everyone was sliding, nose over tailfin, freefalling, out of the tree trunk and splashing into blinding light and chilly water.

This new body of water was even larger and deeper than the reservoir. When the barrel emptied out, Smallie quickly lost track of all the other fish who sped away to hide. He spent the first few days in this vast water feeling lost and alone. Sometime later, as he was trolling the bottom for food, he spotted a fish swimming towards him, whose yellowish-gold coloring and dark vertical stripes made him think he was looking at a reflection of himself. He waited cautiously until the fish was near by and then held out a crayfish from his catch. The fish grabbed the crayfish, balanced it on a fin and gracefully opened her mouth to toss it in. They started swimming along together, and Smallie learned that the fish’s name was Rose and that she was an ocean perch who had arrived in the lake a few months before in a barrel truck, just as he had.

Over the next few weeks, Rose taught Smallie to understand the ways of the lake. She was very sociable, always asking questions of the native fish. When Smallie wondered about the name of the lake in which they had been dumped, Rose told him that it was Lake Oneida, in upper New York State. When he wondered why the water was so clear, Rose explained that zebra mussels had invaded the lake a few years before and had eaten up all the plankton, which cleared up the water but also made food scarce. “The clarity of the water is deceptive,” she said. “Some fish have been heard complaining about ‘dead’ spots in the lake, where it is difficult to breathe, so you have to be careful about where you swim and where you sleep.” When he wondered whether some of the most tasty-looking food could be dangerous, Rose explained that it was rumored that the Pro-Bass Fishing Tournament was scheduled to make Oneida Lake its primary stop later in the summer. It was at these times that mouthwatering worms and luscious prey dangled from above, and a fish could disappear in an instant. This reminded Smallie of the dangerous caddis flies that had tempted his relatives in the trout stream. All in all, Rose painted a nasty picture of Oneida Lake life, and Smallie was beginning to be discouraged that he would ever find a safe home.

Nevertheless, Rose and Smallie became fast friends. They both preferred to spend the bone-chilling winter near the bottom of the lake, where the water was a constant temperature. Rose liked to hang out with a group of fish from her native family – yellow perch and walleyes.

One day in early spring, Rose and Smallie were cruising along in the sunlit shallows, looking for mayfly snacks, when Rose twirled towards him and said, “I remember, I meant to tell you that I overheard a conversation at the Scale Salon about a gigantic lake that leads to a river with crystal clear waters and lots of rock ledges farther north.” When Rose was excited, she spoke very quickly in long, involved sentences. “It might be difficult to get there – up a narrow feeder river – with many branches – maybe giant fish lie in wait – to ambush . . . ” She hardly needed to say more. Smallie’s spirits immediately brightened. “I know how to navigate rivers much better than big water,” he interrupted her. “I inherited wanderlust from my father – he was always ready to go. Yes, Rose, let’s leave this nasty lake and go exploring to find a place where we belong!”

Even though he sounded brave, Smallie was counting on Rose to be his traveling companion. He was resourceful and had a good sense of direction, but she was wily and quick and made friends easily. He thought they would make a good team. She agreed.

The Perilous Journey

Smallie and Rose made up their minds to set out as soon as possible. They wanted to get to the gigantic lake before the hot summer sun burned up the top of Oneida Lake making their gills red and puffy. First, however, Rose wanted to consult her Uncle Wally, the walleyed pike, who lived in the swift current at the mouth of the Oneida River.

“The river currents are tricky,” Uncle Wally warned her over a bowl of slime soup. “There are boulders and rapids. Swim fast and keep to the center of the channel. Turn north when you come to the Oswego River, which is wider, slower water.”

As Rose was gathering information about the journey, Smallie prepared provisions. He found an old piece of netting snagged on a branch near the shore that he folded over to make a pack which he draped over the spikes on his dorsal fin. Smallie prepared provisions. Skimming along the shoreline, he scooped up emerging nymphs and caddis worms, and, using his clown skills, flipped perfect tosses with his tail fin to fill his new backpack with food for the journey.

On May Day, the first of May, they were ready. Smallie slung on his pack; Rose high-finned her friends in Oneida Lake, and they darted up into the Oneida River heading for Lake Ontario. In the daytime, they struggled upriver against the current, and in the evening, they rested along the rocky shoreline.

One night, after they had feasted on provisions from Smallie’s pack, Rose brought up a question that had been on her mind for weeks: “Why are you called ‘Smallie’,” she asked. “Because, really, you are not that small. And, besides, I have seen whole schools of fish that look just like you. So, to me, you are neither unusual nor small. Don’t you have a proper name?”

He took a deep breath and began to tell his life story: “I’m from Trout Town USA . . .” when Rose interrupted him. “Um, you don’t look like any trout I’ve ever seen!” He paused and watched her eyes dart back and forth. It seemed that she – Rose – might have the answer to his life’s puzzle. “I would wager three crayfish tails that you have all the markings of a small-mouth bass,” declared Rose. “And, as I recall, Trout Town USA is actually a place called Roscoe – yes, now I remember, Roscoe, New York. But you are not a trout from Trout Town USA, so, perhaps, I’ll just call you Roscoe – Roscoe Fish from Roscoe, New York. That sounds better than Smallie, don’t you think?” Without waiting for an answer, she spun around and paddled forward, brushing her soft orange fin affectionately against his scaly cheek: “Pleased to meet you, Roscoe!”

Long ago, scientists discovered that the heartbeat of a fish varies with the water temperature of its environment – increasing as the water temperature rises, and decreasing as it drops, but, for once, the increase in Roscoe’s heartbeat did not have anything to do with the water. His inner temperature was warmed and his heart beat faster knowing that he had found a true and lasting friend in Rose, and that Rose recognized him for who he was. Little did he know then that Rose was actually his cousin in the larger fish family known as Perciformes.

After about a month spent swimming up the horse-shoe bends and swirling currents of the Oneida River, Roscoe and Rose came to the “T” where the waters converged with the Oswego River. They had been told by Uncle Wally to turn right, which was north. Swimming in this river was easier; but just before the river emptied out into Lake Ontario, at the city of Oswego, they came upon an impenetrable wall. The wall turned out to be a gigantic dam that created electrical power for the city, beneficial for the people of Oswego, but blocking fish from traveling upstream.

Roscoe and Rose were stuck, and they began to worry that they would never be able to get up to the big lake. As they were treading water and wondering what to do, Roscoe noticed some yearling steelhead trout playing among the boulders at the edge of the dam. Because steelheads were his mother’s distant cousins – the migrating version of rainbow trout – Roscoe could speak their language. He motioned to Rose to hide by a sheltering rock while he swam over to find out what they knew about getting upstream.

“Healthy fins!” Roscoe shouted in trout talk. “Come on!” A little steelie beckoned. “Secret entrance! Chute!” Trout do not speak in complete sentences because they are moving so fast most of the time. “Gushing water!” The steelie squealed. “Big shape – pull us up! Beat fins! Doors open! Pow! Magic! On top! Lake water gone! Ride rapids back down!” Like a searchlight’s rotating beam, the steelies flipped their shiny bodies into the rock wall and disappeared.

Roscoe squinted after them into the shadows, excited to discover a passage to the big lake, but scared of the idea of a chute that fills up and drains like a barrel truck. “Follow, follow, follow,” he heard the words echoing somewhere inside the wet wall. “Fish pass. Hurry up!”

Using the sensitive feel of his scales, Roscoe slid along the dark wall. He came to a gap, tucked in his fins and squeezed through. Once inside, his eyes adjusted to the dark and he saw a large, rectangular opening – a chute – that led upwards. He could just make out the tails of the steelies beating through a cascade of bubbles. But, instead of following them further, he turned back to get Rose.

“Let’s go!” he exclaimed, as he nudged Rose out of her hiding place. “We have to get to the chute before it fills up with water! We could be in the big lake before breakfast!” They shimmied through the crevice and started upwards. Instantly, a strong gush of water knocked them tumbling nose over tail. Paddling with all their might, they puffed out their gills to stay upright. “Keep close,” Roscoe yelled to Rose over the roar of the churning water.

The chute spat them out like a bubble from a toy water pipe into a gigantic tank, and Roscoe could see huge dark shapes bobbing above. They huddled under one of them, frantically beating their fins as giant whirlpools churned the surface to white.

They had entered a lock for boats, a manmade channel with heavy doors that can be filled or emptied to raise or lower the water level. By use of a lock, boats can avoid differing levels in a river, such as rapids or falls.

Just when Roscoe and Rose thought their fins would fall off from exhaustion, the turbulence suddenly stopped, and the water became as smooth and quiet as the deep pools in the calm river that Roscoe remembered from his youth. Daylight was peeking through the big doors, which had begun to roll slowly open at the other end of the tank. The steelies all raced out from their hiding places, clapping their fins with glee. Roscoe could see the sun just rising over the endless expanse of horizon that he supposed was the big water of Lake Ontario.

Feeling a tap, Roscoe sensed his mind swimming back up into consciousness. There was Percy in his chef’s apron, taking a break from the hot galley.

“Good morning, Roscoe,” Percy blubbered cheerfully. “Nice weather now, but I hear there is a Nor’easter brewing for tonight and tomorrow. That means that breakfast will be slow, but dinner will be packed - no one will want to hunt for food late in the day in the murky water churned up by big waves.”

Roscoe nodded in agreement, his attention snapping back to the present. He looked at his deptherm. Percy was right – the water-temperature gauge was plummeting. It was time for him to head back home to his cave to make preparations.

Once there, he piled seaweed cushions up against the mouth of the cave and waited for the storm to commence. Inside the cave was quiet and calm, and he lay down on his moss bed and dozed off. But in his dreams, he continued to relive the story of his adventurous journey with Rose.

[All illustrations by Sarah Bodine, ©2024.]

By Sarah Bodine ©2024.

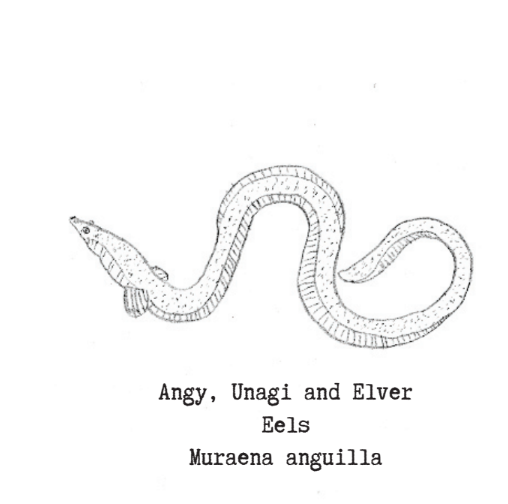

Sarah Bodine is a writer, editor, designer and book artist. She spent the summers of her childhood at her great-grandfather’s house, known as Cliff Cottage, on the Ontario side of the St Lawrence River near Rockport. The three Keats children were her cousins, and she often ran an outboard across the Canadian channel to spend the night on Pine Island. John Keats, fondly known as JK, made Roscoe Fish the main character in his bedtime stories, which were loved by all the children. To this day, the next island generation is forever looking for Roscoe under the boats in the slip.

[From the Editor: Again, for Episode II, we send deep appreciation to Sarah Bodine and her Keats cousins. Those of us who read JK (John Keats, Pine Island) books will smile and thank them for the opportunity to read more - even if in the imagination of Sarah and her cousins. Many authors and readers will know that our TI Life articles are usually limited to 1,200-1,500 words - but this series of short stories about Roscoe may be longer - long enough for all young River Rats to want more! The good news is there will be 8 more Episodes!]

· Volume 19, Issue 1, January, 2024: Introduction: Roscoe Fish Stories by Sarah Bodine

· January, 2024: Episode I: Roscoe Fish "Goes Boying"! by Sarah Bodine