A Requiem for Silenced Waters . . .

by: Craig I. Stevenson

Part I

In my memory, they are there in my grandparents’ basement, sitting on a workshop floor. Smooth and imperfectly roundish, each is scrawled with the words “Long Sault Rapids.” I have inherited them along with the photographs that tell of their story—a series of faded slides from 1957, of people familiar but younger, and of a place disappeared.

The life of the Long Sault Rapids ended abruptly with the construction of the St. Lawrence Seaway and Power Project. For a brief window of time, the awe inspired by their power was transformed into curiosity as a riverbed lay drained and exposed to the world, before its permanent submersion.

That short period left a legacy of memory, linked to the destruction of one of North America’s greatest natural wonders. Stones, musket balls, and photographs tell a story of what remains from the briefest of journeys back into geological time.

Part II

The story of these rocks is part of a broader saga of a geophysical feature transformed suddenly in mid-twentieth century North America. The Long Sault Rapids were timeless, until their time stopped.

Of the sets of rapids along the St. Lawrence upriver of Montreal, the Long Sault Rapids were the most dramatic, with a 59-foot drop in elevation over six miles above Cornwall, ON. The concentrated whitewater at this location created a succession of human histories. Early Iroquoian peoples camped along them to fish for spawning sturgeon. Upper Canadian authorities built a canal alongside them to facilitate travel around the obstacle that they posed. Timber rafts drifted down through them, as did a variety of early steamboats, well into the twentieth century. A small number of adventurers canoed down them.

And then they were gone, the victim of having been located at the point where the St. Lawrence Seaway and Power Project would dam the River to create a deep head pond as the centerpiece of that 1950s megaproject.

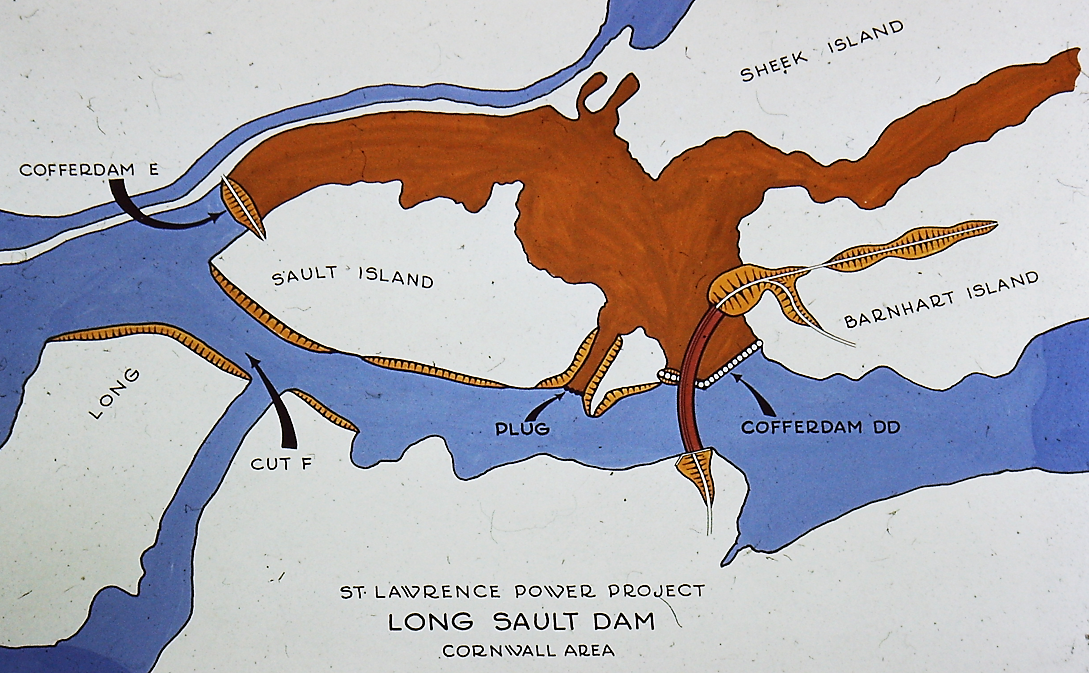

To build electrical generation and water-level control dams at the downstream edge of the rapids, the River’s flow was diverted to create a dried riverbed upon which work could proceed. A channel cut through the adjacent Long Sault Island and a stone-and-earth “coffer dam” near the village of Dickinson’s Landing allowed project engineers to bend the River’s flow away from the areas under construction.

Dumped earth and stone from a cable-and-bucket system spanning the River at the upstream edge of the rapids gradually choked off the volume of water flowing over the rocks, leaving an ever-diminishing flow of water. By April 1957, the “de-watering” of the rapids was complete. That roar of whitewater—one of the most impressive on the planet—ceased to exist as a distinct geological entity.

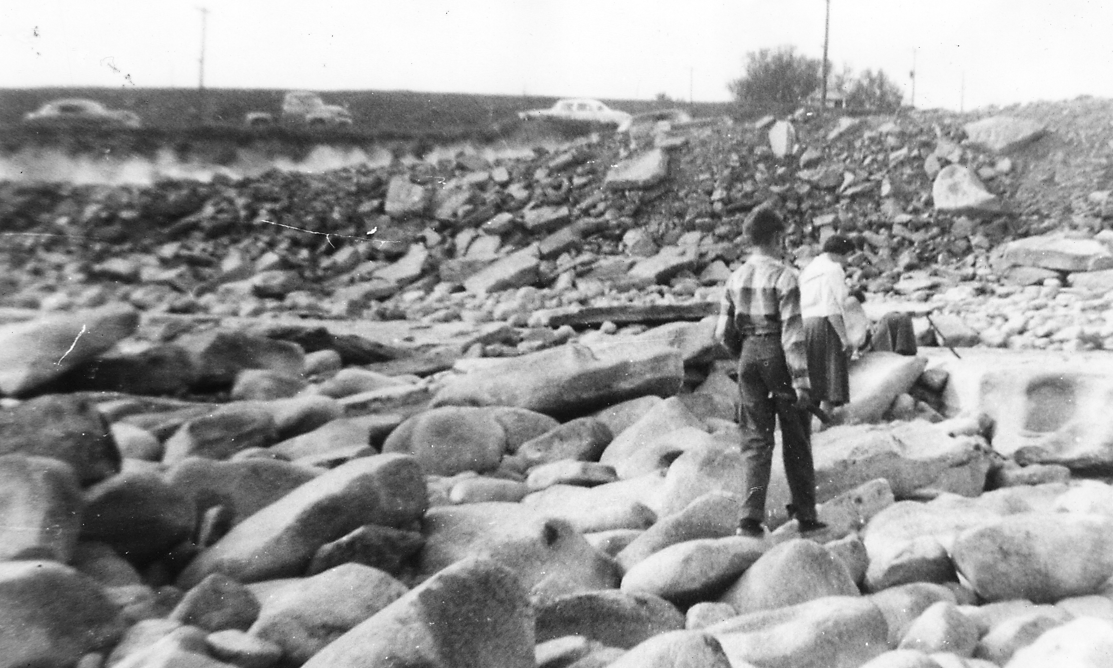

Absent its water, the River was a spectacle of the unimaginable and the unnatural, a riverscape of rocks that looked naked and otherworldly.

Two points are worth noting here. First, those living along the River had never known a world without the sight and the sound of the rapids. To anyone living in Dickinson’s Landing or Moulinette, the rapids were as familiar a sight and sound as a coastal dweller’s rhythmic ocean waves.

And consider the year. In 1957, many riverside residents had been born into a markedly slower world of horse-drawn power and of steam-powered River vessels, with electrical power still in its infancy. To see the rapids drained must have been a psychologically stunning sign of modern humanity’s ability to manipulate and extinguish the full power of the natural world.

Part III

Through those dried-out months of 1957, they arrived to explore the skeletal remains of the rapids. By modern standards the public enjoyed remarkably easy access to the site. Photos of the period show cars lining the wall of the Cornwall Canal, leaving explorers to scramble down the River’s side of the wall and into the emptied bed.

Contemporary accounts overlook this part of the Seaway story. Authorities and media observers emphasized what would result from the project’s construction, not what would soon be lost forever. That tendency is in keeping with the mindset of the era—so neatly summarized by the area’s Chesterville Record in an editorial statement that it would “be glad when the waters rise and cover the scars made by progress.” Officially, the focus was firmly forward.

But come they did, in a popular movement unscripted by authority and prompted by reasons we can only guess at. In photographs and words and artifacts, these impromptu explorers left a legacy of insight into a place opened for a slender moment of time.

With the volume of flowing water subtracted from the equation, what remained of the rapids was a jumble of rock that left various impression upon being left exposed.

Local histories give honourable first mention to Captain James Stephenson of the Rapids Prince, the Canada Steamship Lines steamer that had run down the rapids for decades. Stephenson was the last person alive who had piloted a large vessel through these waters. Wording varies depending on source, but the statement stands in any form—seeing the rocks exposed, Stephenson stated that he’d never have sailed down the rapids had he known what lay below the water’s surface.

An understandable sentiment, but not one that tells the full story.

For those few months, visitors to the riverbed were free to explore, to discover, to make of this unnatural scene what they wished. That exploration could pay tangible dividends.

Arthur Raymond, a teen from nearby Sheik’s Island, made headlines with the four ship anchors and eleven artillery shells he found. These items were believed to have been lost from American naval vessels running down the rapids during the War of 1812. Raymond had youthful curiosity on his side, enhanced by local familiarity and perhaps a sense of urgency knowing that his home island would soon be almost completely submerged by rising floodwaters.

In keeping with the geological spectacle into which the visitors wandered, the rocks themselves became souvenirs. Millennia of powerful currents had worn rocks smooth, particularly those that had found crevices in the riverbed and literally drilled themselves into “potholes” on the River’s bottom. The smaller rocks could be carted home. How many were taken is unknown, but enough to have made an impression on the area’s historical memory. And why, really? My grandfather spoke of the power required to wear a stone so smooth, and so perhaps they were taken as a reminder of what would soon cease to exist. For locals who had grown up with the rapids as an essential element in their personal landscape, that motive might be reason enough.

The photographs are invaluable. They capture an unrepeatable moment in time when people, who could not quite believe that they would ever see the rapids this way, scrambled to create images of a time and place they knew would soon be gone.

Families pose dutifully and children scramble across the empty riverscape. Some, taken from a distance, show people as mere flecks on the broader, sun-bleached vista. In all of them the rocks are the focal point, as was likely intended. The massive flat tablets of rocks that created an uplifted brow of whitewater at the rapids’ center were a particularly favoured backdrop.

The photographers, the explorers, the souvenir collectors—all of them stood at a place exposed only so briefly, a hinge of time within another short span of time that destroyed a unique section of the St. Lawrence River.

Part IV

As surreal as that experience must have been, there is little evidence of that sentiment in the visual record created over those few months. One expects a certain dramatic tension to appear—but that is, perhaps, a modern sensibility coming to the fore. Decades later, we know how the story ends, and what was lost in a moment of time born of unique circumstances.

The rolling froth of the Long Sault Rapids disappeared with finality on July 1,1958 when dynamite blasted earthen coffer dams and waters filled the power project’s head pond. That mystic water held the promise of movement, of danger, and of potential. When the magnetic power of those flowing waters disappeared, it left a distinct void in the lives of those who had been touched by them.

Deep below a blanket of smoother waters, the history and geology of that riverbed remains hidden, though the sight and sound of those rapids lives on in photographs and sketches, in local lore, in collected fragments, and in aging memories of a natural wonder silenced forever.

By Craig I. Stevenson

Craig Irwin Stevenson grew up in Cornwall, Ontario, and spent an inordinate amount of time on and along the River, at his maternal grandparents’ cottage, on Moulinette Island, the easternmost of seventeen islands created by the Seaway flooding. He is a history teacher at Tagwi Secondary School, in Avonmore, Ontario, and never misses a chance to tell his students that the River they see today, was once a very different place.

Be sure to see Craig Stevenson's other River stories here.