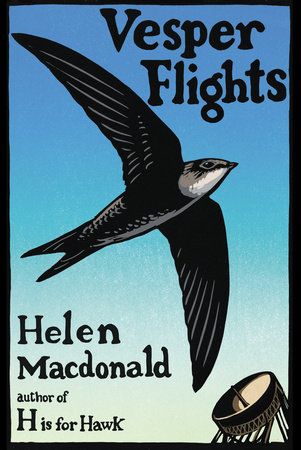

Vesper Flights, a collection of essays by Helen Macdonald (Grove Press)

by: John Swift

Helen Macdonald brings an intensity to each of these 41 essays that explains why she is, in the words of her publisher, “one of [our nation’s] most important nature writers. Vesper Flights is a captivating and foundational [discussion] about observation, fascination, time, memory, love and loss and how we make sense of the world around us.” For example, she investigates the flying patterns of a swoop of swifts (“vesper flights”), and concludes that they provide an example of a functioning community, one that remains united in the face of trouble. Thus, they make the right decision in the “face of oncoming bad weather, in the face of clouds that sit like dark rubble on our own horizon” and that decision is to stick together like a swoop of swifts.

Golden Orioles, a rarity in England, when seen through binoculars, “are never more than the size of a fingernail at arm’s length, exactly the size of the visible sun.” Did you know that purple martin fledglings leave the nest, fly about, and return to the nest? I had always assumed that birds left the nest once and for all. These purple martins are metaphors for the modern family.

The metaphor of summer storms explains the current waiting of nations for the next awful thing. “No weather so perfectly conjures a sense of foreboding, of anticipation and waiting, as the eerie stillness that often occurs before the first fat drops of rain, when storm light makes luminous all roofs and fields and strands black silhouettes of trees on the horizon. This is the storm as expectation. As solution about to be offered. Or all hell about to break loose. And as the weeks of this summer draw on, I can’t help but think that this is the weather we are all now made of. All of us waiting. Waiting for news. Waiting for Brexit to hit us. Waiting for the next revelation about the Trump administration. Waiting for hope, stranded in the strange light that stills our hearts before the storm of history.”

Aristotle believed that birds hibernated over the winter and fishermen in the 18th century claimed they could pull “clumps of live swallows from beneath the ice on winter ponds,” but these opinions were pretty much disenfranchised when a German hunter, in 1822, captured a stork with an iron-tipped wooden spear from Central Africa through its neck, resolving where storks spent their winters. Out with the theory of universal bird hibernation. Today, thousands of birds and animals are satellite tagged and their migratory progress, or lack thereof, can be followed on clickable Google Earth icons. The British Trust for Ornithology follows individual cuckoos, which, while expensive, enabled Helen to tell us that Cuckoo David had just landed back in Wales, from his winter sojourn to the African forests.

There is a chapter on why trees are dying, because of globalization where imported plants and flowers harbor their own diseases, not dissimilar from the pilgrims killing off the native Americans with measles, smallpox, and flu. Included is a sentence describing the efforts of a team from the SUNY (State University of New York) College of Environmental Science and Forestry, inserting wheat genes into chestnut embryos to increase the chestnuts’ resilience to attack. This is mostly important to me because I graduated from the aforesaid college some years before we began those genetic studies. I worked on drilling holes by swinging sledge hammers at hand-held bits, and occasionally, of course, the odd thumb, poor fellow, then stuffing the holes with dynamite and blowing up the granite mountains, building forest roads. A work of lesser finesse.

Helen attends a show of bird keepers who imprison goldfinch, ducks, and geese for life to satisfy their own desires but most birds prefer to be free and not have their wings clipped. Helen walks away from the show. “Outside the bird show, I hear a goldfinch singing from the top of a sapling behind me. While my boyfriend walks on to the car, I stop and listen for a while to the bird that is calling a claim to the whole of its life. It sings of seeds and thistledown, of mates and flights and the fragility of eggs in a moss–and–cobweb nest, and of territorial battles and parasites and sparrow-hawks and scarcity and stress.”

All of this is best consumed in small doses. Something like profiteroles. One or two might be a magical dessert, but a dozen at once is way too many.

By John Swift

John Swift was born in High Flats, New York, about ten miles from Potsdam. He attended to a one–room school and his teacher gave him Zane Grey’s "Sunset Pass" as a 5th grade Christmas present. Turned out to be a life saver as he started to read and hasn’t stopped. He had relatives that lived along the St. Lawrence River and visits created many fond childhood memories of the Thousand Islands. After an active career in business John went back to the University of Chicago to study the classics leading to his writing several novels. The latest is his “Sheriff Gogebic” crime series: “Catch and Release.” (about musky fishing!) He also writes occasional columns for the University of Wisconsin’s online literary newsletter called Extra Innings.