Uncommon Beauty

by: Chris Murray

“To most people, I am sure, the beauty of nature means such features as the flowers of spring, autumn foliage, mountain landscapes, and other similar aspects. That they are beautiful is indisputable; yet they are not all that is beautiful about nature. They are the peaks and summits of nature’s greatest displays. Yet, how much is missed if we have eyes only for the bright colors.” ~ Eliot Porter

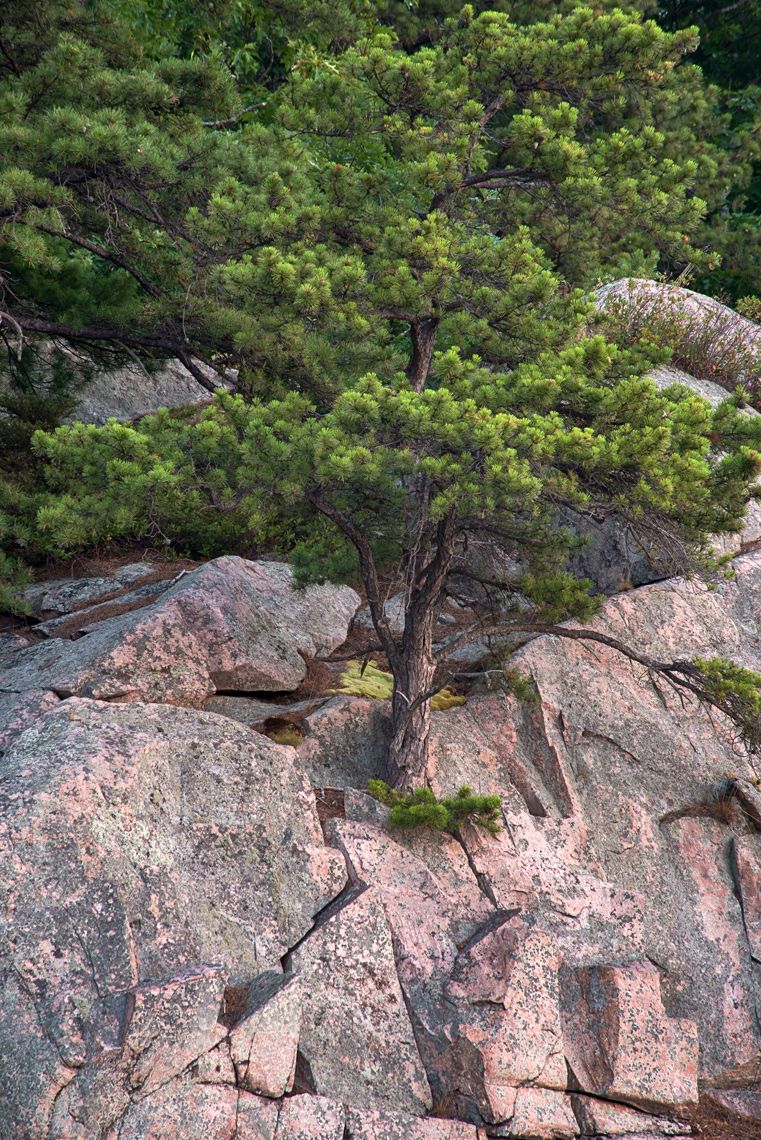

Emerald islands that appear to almost float upon the cobalt blue waters of the St. Lawrence River. Brilliant sunsets that light up the sky and water in fiery shades of orange and red. The natural beauty of the Thousand Islands is manifested in many forms, from the granite shorelines and forested islands, to the abundant wetlands and lakes of the surrounding area. It is a region of almost unparalleled beauty that is obvious to even the most casual observer. But it occurs in other ways as well, ways rich in subtlety and nuance that may go unnoticed by those unable to see beyond the spectacular. These are often scenes within a scene, smaller pockets of beauty that comprise a larger whole. It is a beauty that reveals itself to those who see with their eyes, mind, and heart. Those who take the time to look beyond nature’s more gaudy displays will be rewarded with an even greater appreciation for this most magnificent place, as if they are seeing it with fresh eyes.

I began photographing the Thousand Islands in earnest in 2007, when I moved back to my home state of New York. After a period of several years, I noticed a growing sense of frustration and displeasure with the photos I was producing. Despite my intense affection for the area, I was finding it very difficult to photograph to my satisfaction. It was not that my photos were flawed, at least not in any technical sense. They could best be characterized as competent, yet nothing extraordinary. For the most part, my photographs were objective in nature, recordings of literal appearances devoid of personal narrative and imagination (photography is an art form after all, and what is art without self-expression?). Anyone of similar skill could (and a few do) produce very similar looking photos. In short, they were “pretty” photos that were lacking in originality and creativity.

In time, I realized that I wasn’t expressing my true vision. It was being suppressed by a desire for popularity and acceptance. I was creating for an audience, more than myself. It was also being clouded by judgements and biases as to what constitutes “beauty”.

Once I let go of all preconceptions and biases (and my ego), my true vision began to come through in my work. No longer beholden to the standard definition of beauty, I began to see beyond the obvious and spectacular and to create images that reflected my own sensibilities and way of seeing. I became attracted to subtlety and nuance, and my photographs began to become more much subjective in nature.

As photographic artist John Radigan states so eloquently, in the foreword of his book, The Adirondack Heart, “My photographs are not meant to literally document the Adirondacks. They are my way of making visible the relationships I sense here.” In much the same way I view my photographs of the Thousand Islands as a reflection of my emotional response inspired by a subject - in this case a place - more dear to me than any other.

By Chris Murray

Chris Murray is a full-time photographer, instructor, and writer. His work has appeared in several magazines, including Popular Photography, Shutterbug, Adirondack Life, Life in the Finger Lakes, and New York State Conservationist, among others. Chris teaches classes at the Thousand Islands Arts Center in Clayton and at Jefferson Community College. He is a staff instructor with the Adirondack Photography Institute. You can see all of Chris' Depth of Field TI Life articles here and for more of Chris’ work visit https://chrismurrayphotography.com/.