Ticked Off

by: Paul Hetzler

Mosquitoes suck and black flies bite. But enough complaining.

It seems the price we pay for warm weather is the onset of bug bites. Clouds of mosquitoes suck the fun out of camping or canoeing, and it’s no picnic for those who work outdoors, either. However, just one bite from a deer (black-legged) tick can put you out of commission for the whole season – maybe longer.

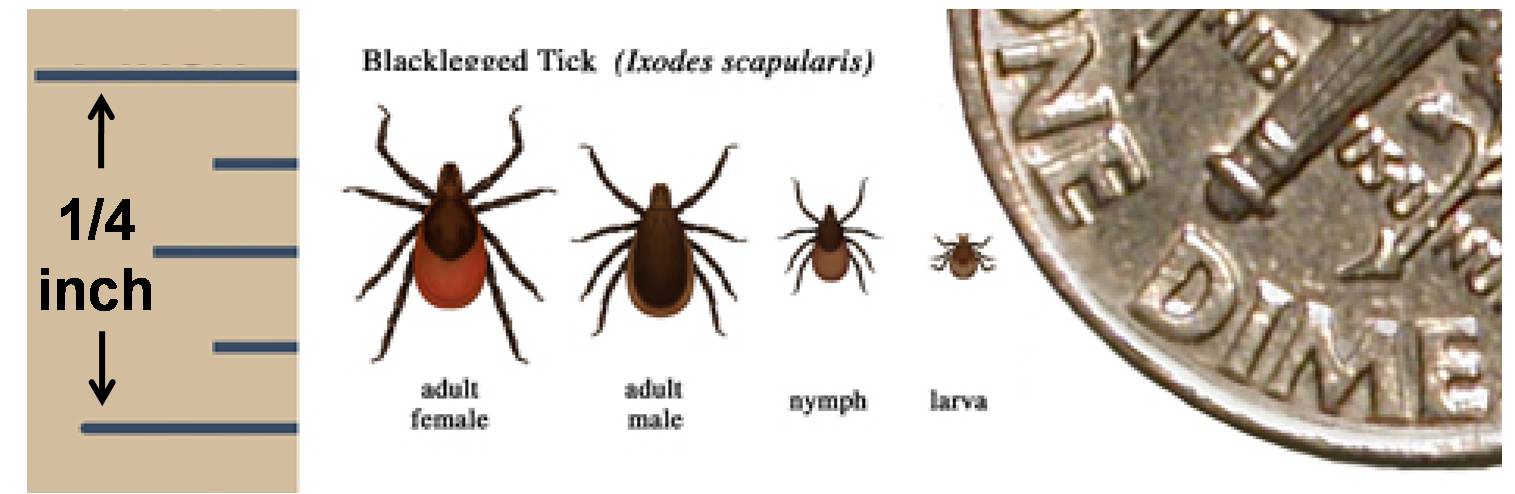

As recently as a decade ago in northern NY State and southern Ontario, it was unusual to find deer ticks on you even after a long day outdoors. Technically an invasive species, the deer tick (Ixodes scapularis) is another gift from down south, having gradually moved north from the Mid-Atlantic and lower New England states. Generally speaking, they are now widespread in the northeastern US and southeastern Canada.

Deer ticks are arachnids, in the same family as spiders – smaller, but far more dangerous. They are known to vector Lyme disease and a slew of appetizing scourges, including babesiosis, erlichiosis, anaplasmosis, Powassan virus and more. It’s fairly common for a tick to transmit multiple diseases at the same time.

Our understanding of tick-borne illness has changed drastically in the past few years. If you have literature older than 2015, throw it out (tick literature – save your other books)! As an example, Dr. Nevena Zubcevic, a tick specialist who teaches at Harvard Medical School, contends that the red expanding “bull’s-eye” rash or erythema migrans, once considered the hallmark of Lyme, is actually rare. It may occur in fewer than 20% of Lyme cases.

In 2014, the New York State Department of Health commissioned a tick study in four counties that border Ontario and Québec. The study found that about 50% of ticks there are infected with Borrelia burgdorferi, the spirochete bacterium that causes Lyme (not Lyme’s – those are for mojitos and margaritas). This conflicts with older material, suggesting only about 20% of deer ticks were infected.

In addition, by 2016, researchers had identified two more (deer) tick-borne microbes in the genus Borrelia. These newbies, B. miyamotoi and B. mayonii, can also cause Lyme, or a so-called “Lyme variant.” Sadly, blood tests are not tailored to these recently identified pathogens.

This isn’t to say we need to panic, though feel free if you like. Avoiding ticks would be the most effective course of action, but if you work or play out in the real world, that’s not always an option. The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends using products with 20-30% DEET on exposed skin.

Clothing and footwear can be treated with 0.5% permethrin. Although I am not a fan of pesticides in general, I can’t say enough about how effective permethrin is. It not only repels ticks, it kills them within minutes, something DEET does not do. Another great thing is that it’s a once or twice per season application – permethrin is reported to stay effective through at least 20 wash cycles. Always follow label instructions. Even though permethrin is 2,250 times more toxic to deer ticks than to mammals, it is still a pesticide.

If you’re in the woods, never follow a deer trail. Treat your pets regularly with a systemic anti-tick product and/or tick collar, so they don’t bring deer ticks into the home. Talk to your vet about getting your pets vaccinated against Lyme, (sadly, there is no human vaccine at the moment).

Check for ticks every evening after you shower. They prefer hard-to-see places, such as the armpits, groin, scalp, and the backs of the knees. Also, look closely at the beltline and sock hem – they like to tuck into the edge of clothing.

If you find a tick has latched onto you, the CDC recommends grasping it with tweezers as close to the skin as possible and pulling straight up until it releases. You may have to pull hard if it has been feeding for some time. Use steady pressure – no sudden motions.

Do not use heat, petroleum jelly, essential oils, or other home remedies! The good news is that these treatments usually get the tick to release. The bad news is that they make it disgorge the entire contents of its gut into your bloodstream. Unless you want a disease injection, remove ticks the right way.

While it was once thought ticks did not transmit Lyme until they had been attached for 36 to 48 hours, experts now say that while you definitely have 24 hours, beyond that, you are at risk. But other illnesses can be transmitted within minutes. Hooray, right?

Early symptoms of Lyme disease vary widely – I’d say wildly – from person to person. Early Lyme effects may include severe headache, chills, fever, extreme fatigue, joint pain, night sweats, or dizziness. But the first signs may be heart palpitations. Lyme can also present with sudden and marked confusion as the first symptom. Those symptoms, though uncommon, can occur right out of the box.

If you’ve been bitten by a deer tick and have any of these symptoms, see a doctor right away. Prompt treatment is critical because Lyme can cause permanent arthritis, cardiac impairment, or neurological damage. Most people respond well to treatment, but a few may take months, sometimes more than a year, to recover. It’s a shame how little is known about “Post-Lyme Syndrome” or “Chronic Lyme” beyond that they may involve auto-immune responses, and they devastate the lives of those afflicted.

An important point is that the Lyme titer or Western blot test is NOT a yes-or-no assay. Each lab chooses how sensitive – i.e., effective – to make its Western blot. Of the 36 immunoglobulin “bands” identified by the CDC. for a complete Lyme test, labs typically check for seven to twelve bands.

Individual labs also decide how to interpret their test results. One lab might count two positive bands as a yes-result, while the next may require three bands. Follow this logic: Two bands present – “Stop whining and get to work.” Three bands present – “OMG you poor sick puppy! Take these pills and rest a few weeks.” You get the yes-or-no result phone call, sure - but you don’t get to see your score card unless you insist.

Also, the Western blot is known to have at least a 36% false-negative rate (Journal of Clinical Infectious Diseases, 07/2008). And according to lymedisease.org, “56% of patients with Lyme disease test negative using the two-tiered testing system recommended by the CDC. (Stricker 2007)”

To recap, deer ticks are new; they’re here to stay, and they can mess-up your life in a big way. Use permethrin on clothes and shoes, check for ticks daily, and remove them promptly. Very few Lyme cases involve a rash, and symptoms can be all over the map. Find a doctor who will treat you based on clinical presentation, because testing is unreliable, to put it nicely. For lots more great information, peruse the Canadian Lyme Disease Foundation website at https://canlyme.com/

Now, get ticked off and stay that way!

By Paul Hetzler

Paul Hetzler is a naturalist and an ISA-Certified Arborist. He lives with his wife in Val-des-Monts, Québec.

Visit paulhetzlernature.org for hundreds of articles on trees and critters. His book of nature essays is at https://www.amazon.com/dp/099860609X