The Story of Miss St. Lawrence, Part II

by: Tom Frauenheim

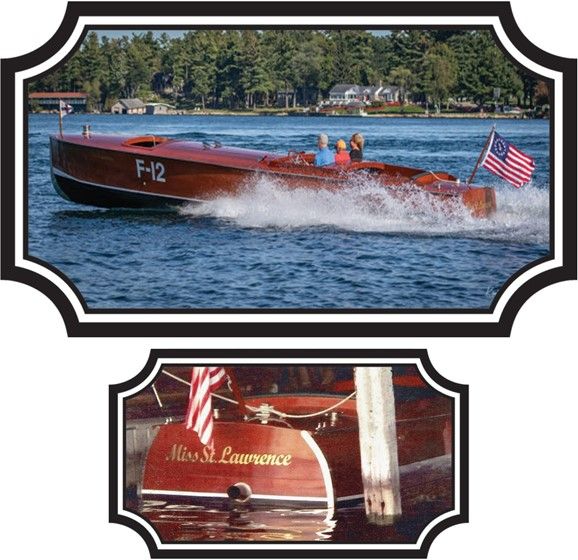

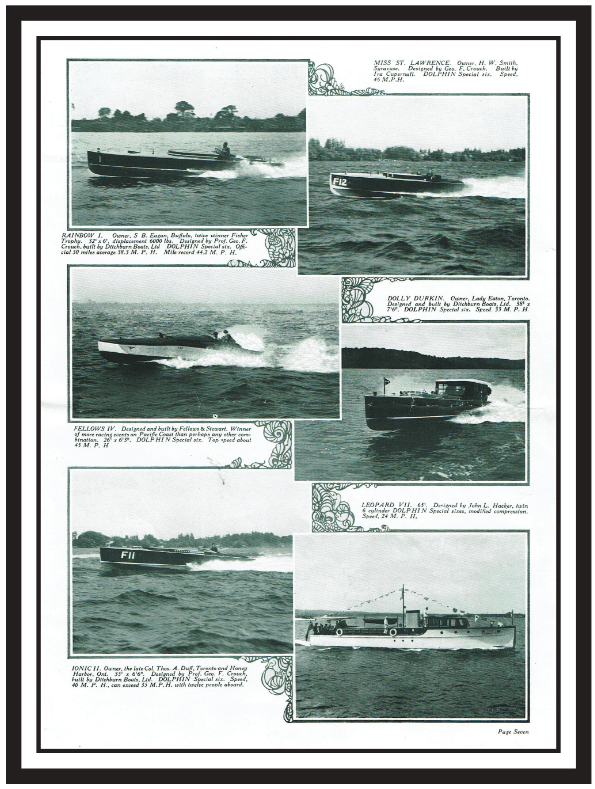

Introduction: As the era of steamboats died out, a new breed of fast, sleek boats powered by gasoline engines rose to take their place. This was the age of handcrafted boats. Many individuals on the St. Lawrence dedicated themselves to designing, building, and racing these boats. Once upon a time, these sleek mahogany boats sliced through the blue of the St. Lawrence, their throaty engines roaring. That was one hundred years ago. Most of those boats are gone. Some are displayed in museums. Only a few still grace the Thousand Islands. This is the story of one such boat that still plies the waters that bears her name: Miss St. Lawrence.

At the end of Part I of the Story of the Miss St. Lawrence (Vol 19, Issue June 2024) we learned that:

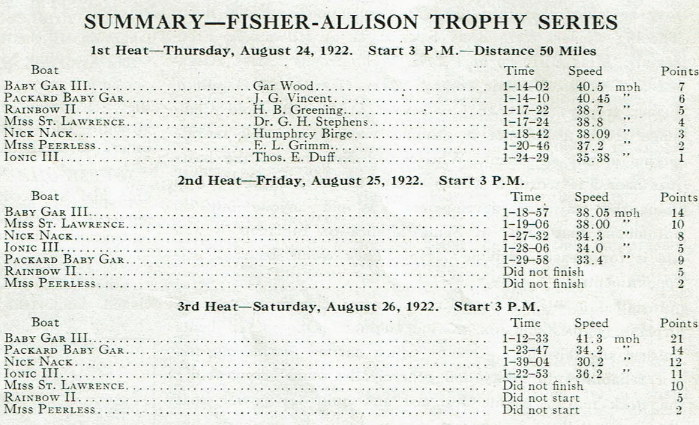

At the end of Part I, we learned that: The third and final 50-mile leg was on Saturday and Captain Cupernall pushed Miss St. Lawrence to the limit, leading all but Gar Wood in his twin engine, 500 hp boat. Lady Luck dropped the ball on Miss St. Lawrence with only three laps to go in the final leg of the race – a connecting rod let go in the Sterling engine, ending a great race for that “marine” powered boat.

After the Race!

After the race, the president of Sterling Engine Company, sorry to see his engine fail, offered Dr. Stephens a new engine for the Miss St. Lawrence if he brought the boat to Buffalo. Severe weather was causing towing problems, so the Sterling mechanic jumped into the engine compartment, removed the side inspection plate, disconnected the piston rod, and shoved the piston up – securing it in position with his feeler gauge. He then removed the spark plug wires and started the engine, running now on four cylinders, and proceeded to Buffalo at 35 mph.

The battle between the marinized aircraft motors and the marine motor at Hamilton caused protests that were not resolved until 1924. In the end, Dr Stephens could not find a marine motor with the power he needed to compete in future races. He had invested over $12,000 in building and powering the Miss St. Lawrence. Sterling Engine Company advertised her speed at 46 MPH – in 1922, Ira Cupernall recorded 49 mph. There were more repercussions to boat racing and engine development in the months and years to come.

Sterling Engine in Buffalo, NY, got into the engine business around 1900. Charles Criqui saw an engine that he wanted to buy. He went to the factory, but they could not or would not sell him an engine. Criqui objected and they responded, “If you don't like it, you buy the company.” He did, and thus started the Sterling Engine Company!

With several investors, Charles Criqui’s Sterling Engine Company became one of, if not the best, marine engine builders in the country. They participated in every Gold Cup Race since 1908, every engine was test run before shipping, and they offered prompt parts and repair service.

Boat racing, while costing a lot of time and money, did help them build knowledge and experience. Boat designers and builders wanted to recommend motors that held up – and the Sterling’s did that. Dr. Stephens already had a Sterling motor in one of his boats. When George Crouch designed the Rainbow for owner Harry Greening, there was no second best – he wanted the best boat design, the best builder, and the best motor – so he chose Sterling.

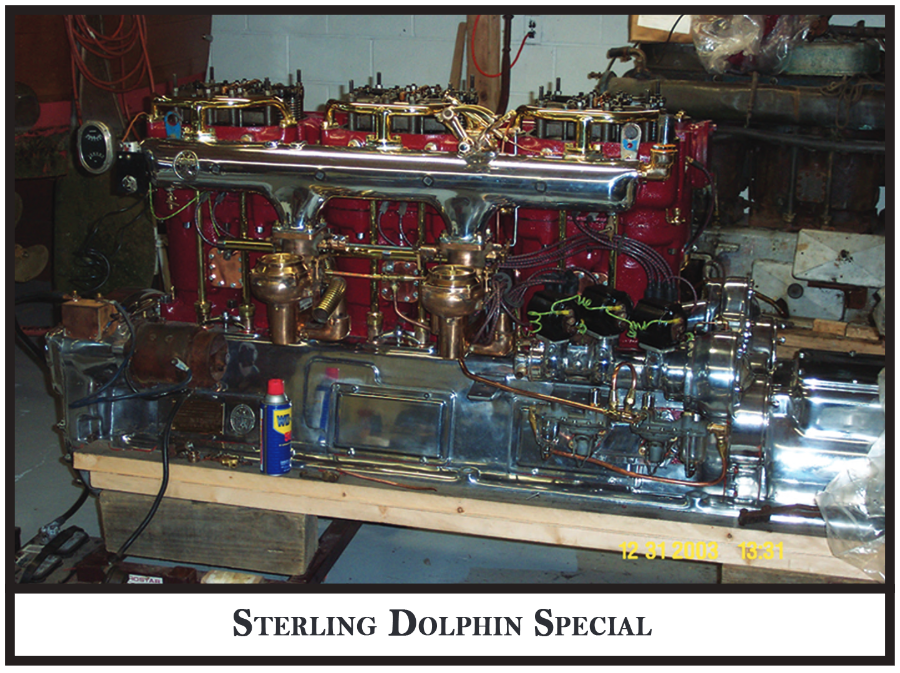

The Sterling Dolphin Special weighted 1950 lbs, against the aircraft engine weight of 1200 lbs. The Sterling crankcase was aluminum to keep weight down. It had automatic oiling to all main bearings, a counter balanced crankshaft, triple ignition, twin cams with two intake and two exhaust valves per cylinder bore of 5 ¾” and stroke of 6 ¾”. This was the high-speed engine turning at 1950 RPM. Built to the highest standards, it proved to be a solid and dependable marine engine for many years.

Fisher Trophy

The 1922 race in Hamilton proved to be the death knell of the Fisher Trophy races. The officials, not wanting to enforce the requirement that engines must be designed, manufactured, and marketed as “marine engines,” let the races go on and waited for the American Powerboat Association (APBA) to figure everything out later. Dr. Stephens and Humphrey Birge of Buffalo filed an official protest against Gar Wood and Jesse Vincent, and in return, Stephens and Birge were protested for not having amateur drivers.

Dr. Stephens had spent a lot of time and money following the deed of gift rules and now was just pushed aside. He asked Sterling Engine if they would build a more powerful engine, but even Sterling wanted no part of future races. Sterling had just built their new Sea Gull model 621 cu. inch engine for the Gold Cup races, and four boats were powered with the engine in 1922. They did very well. Sterling had raced in every Gold Cup race since 1908 and they were also the most powerful and dependable engine in boat racing, but now their support of racing engines stopped. They never built another race engine again after the 1923 decision allowed airplane engines in the races. The boat and engine builders had been betrayed by the APBA when they changed the rules in the middle of the contest. After World War I, the market was flooded with aviation engines that Gar Wood and Carl Fisher had bought up and marinized – they wanted their engines in the races and available for purchase on the boat market.

Discouraged, Dr. Stephens placed an ad in MOTOR BOATING magazine in July 1924, for sale of the Miss St. Lawrence. One of Dr. Stephens’s sons, George III, recalled in a series of letters:

“Sometime after, Hurlbut W. Smith, who was president of the L.C. Smith typewriter company, apparently contacted my dad and the boat was sold to him. “Bert” Smith owned the property known as Indian Isle in the village of Brewerton on the Oneida River, right next to Rt. 11. He took the boat back there, and the story goes that he asked his boatman to take him for a ride in the boat. Bert sat in the back seat and the boatman headed out into Oneida Lake, where he opened her up. He then came to a navigation buoy and having heard about her performance, decided to make a close turn around the buoy wide open. The turn scared Bert, and he told the boatman to take him home. He had the boat hauled out of the water in the boat house, which was too short for the boat so that quite a bit of the stern of the boat was out in the open. He never had the boat launched again and it stayed there about 11 years with the stern sticking out in the weather with the boat house doors open and all the rain and snow blowing in.”

“Smith's wife died in 1935 and he put the boat up for sale. The Combined Boat Tour Company of Alexandria Bay bought it for the engine, which they needed for one of their tour boats called the Thousand Islander. This was about a sixty-foot-long tour boat, which had an open cockpit in front of the cabin and windshield and this open cockpit had a canvas canopy over it, so it was easy to recognize this distinctive boat.”

"The engine was installed and ran in that boat around the islands for probably twenty years or more, until they wore that engine right out. According to the story that I heard from Chuck Thomas, a boat mechanic who is still around Alex Bay. He used to work, and possibly still does work for Hutchinson's. After the engine was taken out of the boat, the hull was parked in one of the slips at the foot of the main street in Alexandria Bay."

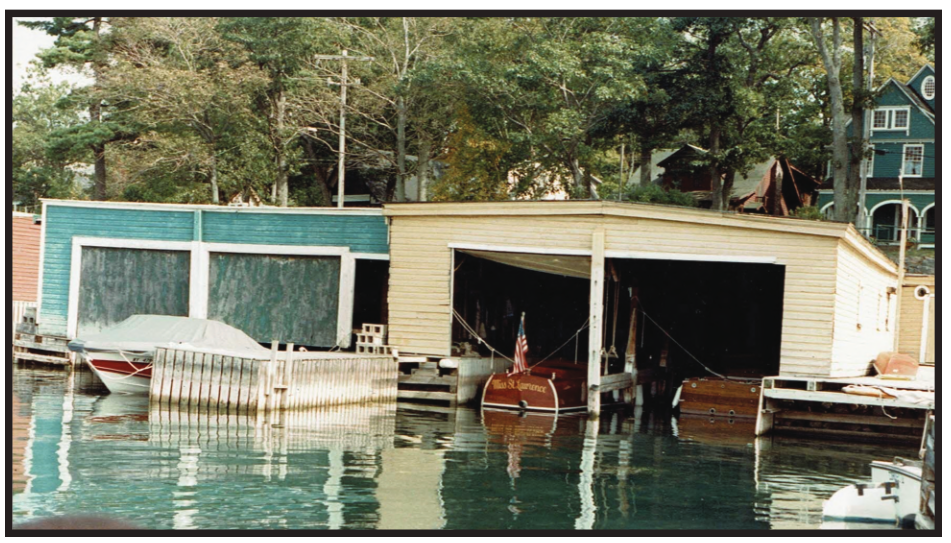

These slips belonged to the Combined Boat Tours Company; this would be at the north end of the village. My brother, Fred, at that time engaged in getting his practice as an ophthalmologist off the ground in Providence, Rhode Island. His long-time friend, Bill Andrews was just starting the practice of law in Watertown, New York and lived in Philadelphia, New York nearby. He happened upon the hull of the "Miss St. Lawrence" as it floated in the tour boat company slip after the removal of the engine. He recognized the boat instantly and inquired about it and found that the company had bought what they considered an old junker because it had a good engine. Bill knew my brother always had an interest in re-acquiring the boat, so he had a talk with the manager of the boat line and finally ended up buying it for $125.00. He then stored the hull in a rented boat house in a string of boathouses in Otter Creek which belonged to the Edgewood Hotel in the Bay.

The boat remained there, out of the water, for nine years when I acquired it from Bill Andrews and towed it up to Thousand Island Park with the assistance of the three Allen brothers who were residents of Thousand Island Park. Cliff Allen is now a Superior Court Judge in California and Dick Allen is a former FBI agent. Bob Allen is an orthopedic surgeon in California. The four of us towed the boat to Thousand Island Park behind my little Cupernall built 22' fishing boat called either the "Frederick" or "The Little Boat" and we hauled her out in our boathouse.

“My dad was very happy to see her come back, so he and I started work on her to restore the finish. She was in pretty tough shape as far as the finish was concerned and she had a little rot in her stem and sternpost. We obtained the services of Ivan Couch Jr. [Ivan Sr. was a famous boatbuilder from Clayton and Junior learned the trade from his dad. The father was tragically killed in a fire in his shop in Clayton.] Ivan Jr. was a very accomplished boatbuilder. He put a new stem in her, again made of white oak. He also removed the transom and stern deck and installed a new sternpost. The stern deck planking was so badly weathered that even sanding long and hard with a belt sander did not bring back the color.”

“I know at one point the plan was to turn the planks over and install them upside down and I believe this is what Ivan did, although I am not positive. Ivan also removed two bucket seats and installed the framework for a new bench seat in their place. He also removed the raised hatches and raised coaming of the windshield supports and widened the engine deck hatches, planning for installation of another engine. The front cockpit was only cut in after correspondence with George Crouch, who assured us it was fully feasible and part of the plans. He also gave exact instructions on how to do it.”

“Meanwhile, my dad and I stripped the boat of its finish and applied several coats of varnish to her. I believe the deck got only one coat of varnish, which was then wet sanded preparatory to applying another coat, but I guess the next coat was not applied. The bottom of the boat was thoroughly stripped and a couple of coats of Woolsey's Vinelast was applied to that. However, the boat was only in the water for the summer of 1922 and was never in service again after that.”

Next Phase

The Miss St. Lawrence stayed out of the water in the Stephens’ boat house in Thousand Islands Park through the 1940’s, 1950’s, 1960’s, and part of the 1970’s. George told the story of how after the war, they were going to re-power the boat with a war surplus PT boat engine. They had contacted George Crouch about installing the engine and he sent prints on shaft installation and mounts. The extra weight over that of the Sterling engine would only drop the waterline an inch! A new engine was ordered, but when it arrived it turned out it was a used engine coated in cosmoline. George returned the used engine, but the new engine was never shipped to replace it. So, the boat sat.

George Stephens said, “In late summer or fall of 1971, Tom Turgeon, who was then director of the Thousand Island Shipyard Museum, approached me with the request that I loan the Miss St. Lawrence to the museum as its centrepiece, in the only building at the time. This was long before they acquired the Otis Brooks property. Later, Tom brought a written contract of loan, which brought E. Herrick Sr, who was acting curator and acting director of the museum, to see me. Then the following June, we entered into a written contract, whereby I loaned the Miss St. Lawrence and a 10 ft sailing dinghy to the museum. The museum people were very pleased to get the Miss St. Lawrence, especially since it was built in Clayton. Unfortunately, there was a change in management in the Board of Directors in 1979, and the new directors decided to use tactics of which I disapproved, to get me and others to donate items that previously had been loaned.

"Miss St. Lawrence" in Stephens' Boat House at T.I. Park

George III put a “For Sale” sign on the boat. And in 1979, I bought the boat and moved her to Buffalo, NY, to be repowered with a Marine Power 340 hp V8. She ran fine! Around 1983, we took the boat to a boat show on the Rideau Canal in Canada, and on returning to the US, dropped the boat at Hutchinsons for George III to use. Since he was only a few years old when she was built, he had never had a ride in it. George loved the boat, took great care of it, stored it in the original boat house, and used it to share the River experience with others. Our relationship lasted more than forty years and I could not ask for a better friend.

The Sterling Engine

In 2002, I received word that “Hawkeye might be selling three Sterling engines to get some cash to buy another vintage car.” It turns out that there was a 6-cylinder Sterling Dolphin Special, another marine Sterling Dolphin 6, and a stationary four-cylinder Sterling GR4. John “Hawkeye” Hawkinson spent a lifetime unearthing and rehabbing mechanical treasures and he did not part with much. When the opportunity came up to buy an original engine, I told my wife, “If it means a mortgage on the house, we need that engine!”

Hakeye and the Sterling Dolphin Special. [Photos courtesy the Author's Archives.]

Because of all the aluminum in the engine, most of the engines were scrapped in the War effort. We were able to strike a deal and the engines came to Buffalo. The Sterling Dolphin Special was rebuilt by Doug Van Lear in Buffalo, and is ready to go back in the boat.

Aftermath

Ira Cupernall built a number of boats each year after the Miss St. Lawrence, and continued to represent the Sterling Engine Company in the Thousand Island Park and on the Clayton waterfront. The testimony to his ability is still seen in the boat today. Ira died March 6, 1929, at the age of 59. His skill in boatbuilding and the determination of Dr. Stephens to build the best boat possible, is evident as the Miss St. Lawrence still graces the River after which she was proudly named.

Today, the hull sides of the Miss St. Lawrence are as straight and fair as when Ira finished building the boat in 1922. The bottom and hull sides are original. The front cockpit and helm seating had been changed in the 1940’s by Ivan Couch. The decks are mostly original, with the original raised part of the hatches removed so that they are now flush. The hatches are a single wide mahogany plank. The hardware is original and nickel plated. Dr Stephens was the medical doctor for the Franklin Automobile Company and was able to have the hardware nickel plated. This process was just being developed, few people had it or even knew about it – but Franklin engineers did have it, and Dr. Stephens was able to have the parts plated so the boat “stood out” from others. Prior to nickel plating, the hardware was polished brass.

Since 1979, the boat has only been refinished down to bare wood a couple of times. The hull side plugs over each rivet have never moved and there is no dark staining or warping on any planks. While the bow in most boats rises when accelerating, the Crouch design in Miss St. Lawrence does not do that. The entire boat lifts on the “full length Vee bottom design.” It is the most comfortable and dry ride in any seat in the boat!

The Miss St. Lawrence is still cruising the Islands of the St. Lawrence after more than 100 years!

By Tom Frauenheim

Tom Frauenheim is lifetime River Rat. When not on the River he lives in Tonawanda, NY. His research into the Miss St. Lawrence will be appreciated.

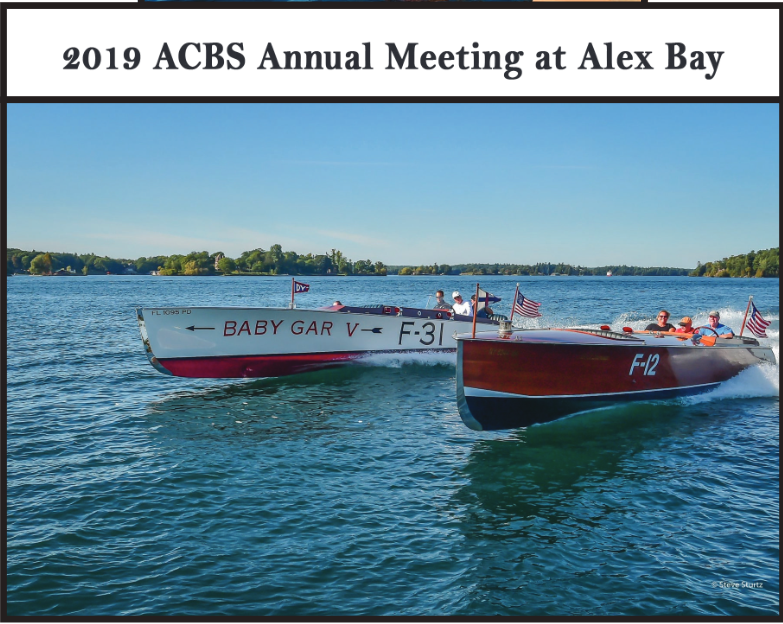

Header photo by Kent O. Smith. Jr. 2019. All photos courtesy of the author.

Comments

K Stephens Posewitz writes: Tom, Thank you so very much for taking the time to so thoroughly research this article. You've sussed out information that I never would have dreamed of! I'm particularly interested in the correspondence between my grandfather and Ira Cupernall. Dad (George III) would have loved this article. You do the Miss St Lawrence justice! BTW, is she still at the River? I truly miss it.