The Grindstone Island Skating Trip

by: Manley L. Rusho

It was the middle of January in 1953, with temperatures about 15 degrees F. A cold night had turned the open waters of the River into a sheet of glass that was about 2 to 3 inches thick. The ice was smooth and clear, and was an irresistible glass surface that had to be skated upon.

Overhead in the boathouse was a hand sleigh of some four feet in length. On top of the sled someone had fastened a wooden box fitted with a set of handles, allowing a person to push the sled ahead of you when walking, or in my case skating. Retrieving the sled from the upstairs, I cleaned the accumulated rust from the runners, and applied a bit of ski wax to the now shinny runners. My pair of Donoghue skates had a blade of about 12 or more inches long that I put on over my leather boots. The boots were a gift from someone, high leather lace ups about 8 inches high and two sizes too big, with plenty of room for two heavy wool socks.

The skates were old, long-bladed, and the front curved upward like Dutch skates, superb steel fastened upon wooden blocks; each skate had a screw toward the rear of the skate. This screw was turned into the heel of your boot until it was firmly embedded. There were slots in the wooden part of the skate and through the slots were straps that, when passed around the boot, made the boot and skate become one unit.

A Thermos of coffee, matches and an extra pack of smokes, a chunk of rope, a canvas tarp, a small axe, and a rifle; I was away to explore this frozen world. Skating and pushing the sled that carried my supplies, I glided out of the bay and moved with ease to the east and to Picton Island Channel. The click of the skates and the metallic noise from the sled runners were the only sounds I could hear. Moving rapidly, I was soon crossing Rusho Bay and into shallow water; it was magical – the bottom of the river was as clear as if I were in a glass bottom boat. I saw sticks and rocks that made impressions in the mud and where some anchor had been dragged along the bottom and even a few small fish. Slowly now, not wanting to miss any treasure, I left Rusho Bay and the only inhabitants on the east end of Grindstone. I saw the smoke from a chimney and that was the only evidence that anyone lived there.

Staying close to the shore to avoid the poor ice on Swift Water Point, the cabin on the point was in about the same state of decay, little sign of any resurrection in the past few years. I continued skating along the shore to where Ken Deedy’s cabin now stands. It was here, between the small island and Grindstone, that Elwood Calhoun and I retrieved the ducks that his father had shot a few years ago. I wondered where Elwood was now; I had heard he was in the service.

I continued to keep my eyes almost always on the scenes on the river bottom. Into the marsh at the plum tree, it was very shallow here, I could hear and see movement. I saw a muskrat moving to get back to his house, a great heap of marsh grass carefully constructed to withstand the harsh winter and the other animals that could tear the house apart. The wet weeds frozen now like concrete, impenetrable now – only the sun of spring will destroy his home. Further into the marsh there was the rock that my brother Milton and I, as kids, had moored the punt and waited for darkness so long ago.

Onward now to Point Angiers and the vast expanse of Eel Bay, so large, so empty, so peaceful – I had to pause here. Coffee time, so I used my tarp for a cushion, to keep my tush from the cold of the rock – this scene was like medicine. At last, the nightmare I had endured in Korea was finally being erased. I drank some coffee, gathered my thoughts, and then proceeded.

Now the bottom of the river is very clear and a bit shallower, with the same bits of debris on the bottom. I have been over this same section of the river sixty-five years later and the bottom is unfortunately now littered with man’s trash. On again, into the marsh near what we called the white house, where I saw more small fish, although I am still hoping to see a large pike or bass. To my left are the now barren rocks of a granite quarry, the huge holes gaping like mouths in a surrealist painting, outlined by the snow.

Yes, there is still more to see, so I skate to the shoreline at the end of the marsh and stop to wonder at the large concrete well casing that houses the spring were Charles Emery bottled water for the hotel on Round Island. So very peaceful; the wind blowing from the north west rattles the dried marsh grass with the dead sounds, dull sounds, and lifeless sounds – life will return in March.

I returned to the River – skating slowly, not wanting to miss a single thing on the bottom. To my left now is the wooden structure of the state land that stands defying the weather. The dock has not fared so well; the top boards are rotted or missing, the cribs have come apart revealing piles of stone once kept in place with timbers now missing, with only large spikes to mark where the timbers had been. Continuing around the little point of Picnic Point, slowly moving along the north side of the point, and still amazed with the show on the river bottom. Along the edge of the marsh grass, I can only guess that the bottom is about two feet from the icecap, so wonderful.

There on the shore, still in decent condition, is my duck blind that I had hand-crafted in November. Along the beach of the big state land, just south of the dock where in December I had walked along the beach and found a few Indian pottery shards and a couple of projectile points. Moving along to the dock, a concrete structure not yet completed, was destroyed by the north wind, crushing ice, and heavy seas. The pavilion stood defiant, unaffected by the wind, snow, or rain and supposedly sits upon an Indian burial ground. Up the hill, a big hill to the locals, is a cluster of pine trees that was planted many years ago by the school children of Grindstone Island. The view from here is breathtaking, complete emptiness with no other living creature that can be seen – even the open water on the western end of Fort Wallace has attracted no ducks – I am alone.

I moved faster now along the north shore of Grindstone, pausing to look again at the two worn and decaying farmhouses that stood on the shore. I had visited those homes while hunting there in November. Most of the outer steps were rotted, the leaking roofs had created a smell of decay. A few pieces of broken furniture littered the floor and the basements contained various amounts of broken canning jars. These houses, now inhabited by animals are only monuments to someone’s dreams. Back in November, the front door hung by one hinge; in front of a broken window was a pile of snow shaped by the wind. In one upstairs bedroom was the remains of a broken doll, head missing, perhaps some little girl’s Christmas gift. I tried to imagine how it was once, long ago, in that elegant home, the noise and laughter now replaced with the haunting sound of the wind moving a broken piece of siding creating a steady bang, bang. My mind flashed back to the doll and I stood on the frozen river and for a second wondered what happened to that little girl. Of the outer buildings, only the tin covered building was in decent shape. The tin building is all that remains today and its hand-honed timbers make it a treasure.

The mouth of Delaney Bay marsh was next. Hoping to skate to the bridge and across the island back to home, a frozen wall of ice maybe two feet tall blocked my passage and beyond the ice wall. The marsh was covered with snow having been frozen since Christmas. I was too tired to skate anymore, so I sat down on my sled and removed the skates. I then headed for home along a very familiar trail, to a mother’s meal.

Only years later did I reflect on the adventure that I had experienced. The river only froze like that under certain conditions; I was so lucky to not only see it, but to take a once in a lifetime adventure and some well-needed therapy.

By Manley L. Rusho

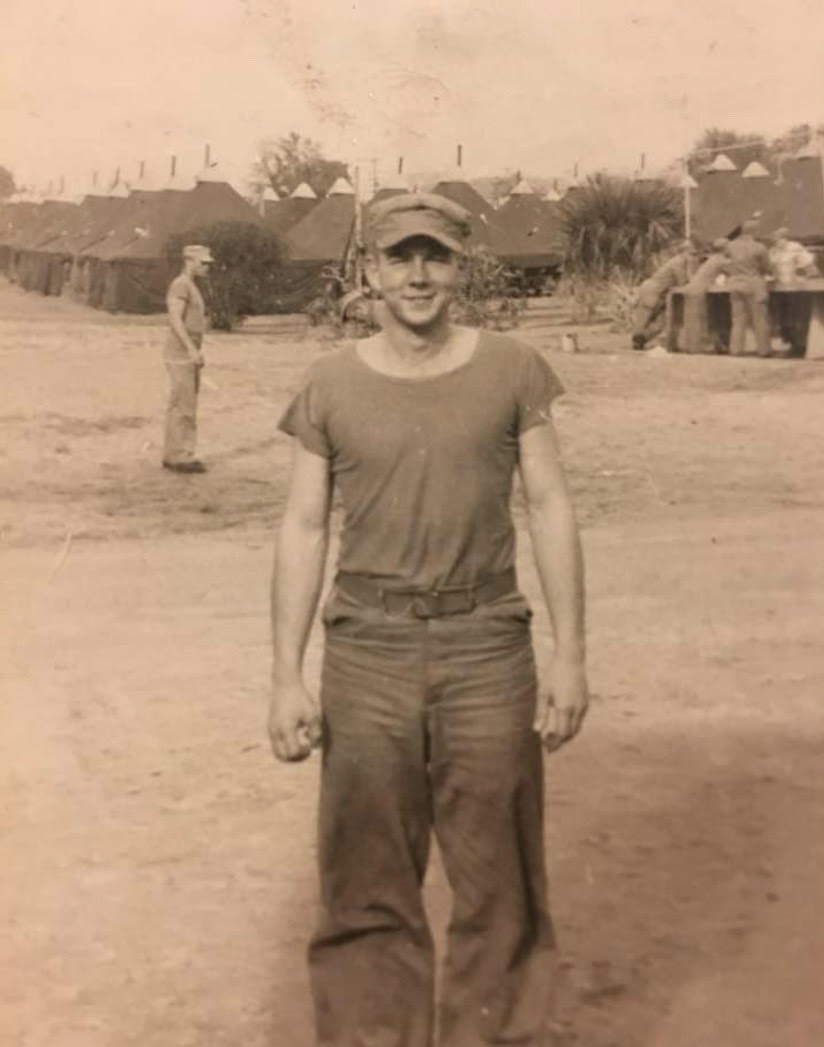

Manley Rusho was born on Grindstone Island nine decades ago. Last year, in 2021, Manley started sharing his memories with TI Life. (Manley Rusho articles) This Editor and his many friends wish him continued good health and we thank him for sharing - as the life and times on Grindstone Island are special and should never be forgotten.

Note: Back in March 2009, Steve Hornsby from Tremont Island, Admiralty Islands, wrote a similar article, "Skates, Hockey Sticks and a Puck." Ice conditions such as described in both articles are rare and taking advantage of those special St. Lawrence River days is prudent.