The Grindstone Island Cheese Factory, (Circa 1940-1954)

by: Manley L. Rusho

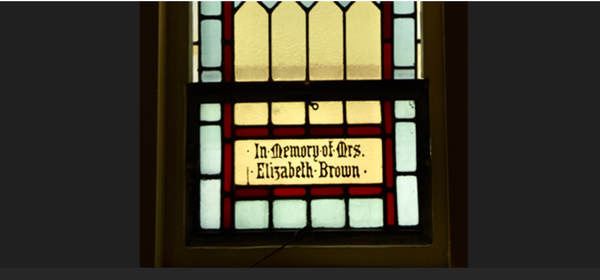

Situated almost halfway between the two schoolhouses on Grindstone Island is the Cheese Factory. This location was probably chosen because it is almost dead center on the island and therefore easy access for all of the dairy farmers. From Audrey’s (Lashomb) book Going Home, Grindstone Island, she writes that the present building was constructed in 1918 after a fire in the original building, which had been built in 1892.

The factory sits on a large rock and the rear of the factory sits on the north end of this rock. The rock was and still is unfarmable. The field east of the factory was farmed, and the north side of the building was a large tillable field. However, it is now overgrown with scrubs and trees. I will try to describe the factory and the surrounding buildings as I remember them from about 1940 through 1954.

Basically, very little has changed since 1918. No improvements were made for the cheesemaker or his family, who lived there during the warmer six months of the year. There was no running water, no indoor plumbing, and no electricity until the 1950’s. Because 99% of the island’s farmers lived without lights and indoor plumbing, the cheesemaker and his family lived the same way. At that time, the cheesemaker’s living quarters were mostly furnished. Many of them had large families and the children attended school on Grindstone during school season.

The factory consisted of two separate buildings. The main building was split into three parts. One part was where the cheese was made. The second part was a huge storage room where rows of cheese sat all formed in cheese cloth; this was the heart of the factory. Another smaller part was where the small coal-fired boiler and the steam engine were located. These machines provided the “power” to run the factory. Outside was a shallow well that provided the water, and next to the well was the outhouse.

I am not sure what year my father (Leon Rusho, Sr.) left employment as a boatman for Mr. Digel on Round Island and became a full-time farmer. Whatever the year, the milk from our cows now increased the production level of milk at the cheese factory by 1000 pounds. Before this time, my grandfather (Manley A. Rusho – who passed away in 1937) had a successful dairy business and provided milk deliveries to Grindstone and surrounding islands. Those days were gone, and the Cheese Factory then received all of our milk. To this day, there are still a few of my grandfather’s glass milk bottles around, marked with his initials “MAR – Frontenac Dairy, Grindstone Island.” There were also many milk cans leftover from the business. I recall my father had a 1937 Chevy pick-up truck and the number of milk cans we had left were more than the little truck would carry.

All of the milk brought to the Cheese Factory had to be in the smaller 10-gallon cans since a new can washer had been bought. Five 10-gallon cans at a time could be steam washed in this new machine. The washing was done with steam heated water and was a real monster, with gushing hot steam and very noisy. After each can was washed, it was dried with hot steam, and then ready to be filled with raw milk. The receiving platform was where both the washer and the milk vat were located. The farmers would pull up with their horse and wagon to the receiving platform. This vat weighed the farmers milk and the amount was recorded. A sample of the milk was assessed for butterfat content, and the weight plus butterfat determined the value of the milk.

The Cheese Factory was open late April until about the end of October each year. Every morning when the factory was open, there was a parade of horses and wagons on the road, mostly a wagon with a single horse. The horses were usually clad with cleat-less shoes. During the dry weather months, the road was hard on their hooves, and they would split. It was common to find a lost horseshoe and as kids, we thought it was equal to finding gold. Some of the light wagons had rubber tires, which were mostly taken off the docks of unsuspecting “summer people.” The big item on the wagons was an inner tube to hold the air. Many of the farmers carried a small tire pump and a wagon jack. These wagons would gather at the factory and line up to deliver their milk each day.

The Cheese Factory became the source of the local island news. The long lines of horses and wagons usually moved slowly, which meant that everyone would get the opportunity to catch up on the latest news. It was here that I discovered in July 1945 that our neighbor Bert McFadden, and his employer Allan Bakewell, had drowned the night before in the River. Mr. Bakewell was a lawyer from New York City who owned the summer home next to our farm.

Other news I remember hearing included a telegram from the war department that told Frank Moneau’s mother that he was missing in action during WWII. Many of the young men on Grindstone went off to fight in WWII. Clark McAvoy and Maxwell Dano were buried in Europe. Lloyd Carnegie is in an airplane at the bottom of the Pacific Ocean. POW Frank Moneau returned, as did Leo Sulier. Of those who returned, most of them eventually left the island for employment and life elsewhere.

I remember a story about my Aunt Carnie (Carlyn Rusho Hammersley) driving our 1937 Chevy pick-up truck, and as she approached the sharp curve at the Lower Schoolhouse (now the Grindstone Island Heritage Museum), she collided with a horse and wagon headed for the Cheese Factory. The horse and wagon were driven by Wellington Black, and it was no match for the Chevy truck. The rear of Mr. Black’s wagon was hit and tore off the rear axle of the wagon. Fortunately, no one was injured, but milk was spilled all over the road. That broken rear axle of the wagon was left there in the ditch for many years, almost as if the axle became a memorial to the new age of automobile and the end of the horse and wagon.

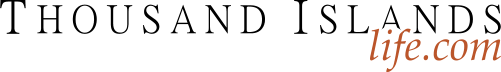

In early September 1945, the war had ended, and school was canceled. I was now attending high school in Clayton, and I rode back and forth from Clayton to Grindstone on the boat The Mary E. The island bus would take us from the town dock to the Upper Schoolhouse on Grindstone and from there, we would disperse and walk home. I remember walking home one day after the war had ended, with three or four other students. Someone stopped to talk to us and told us that the war had been good to the American Farmers and a bonus was being paid to dairy farmers for every 100 pounds of milk produced. This extra money allowed my father to help build an addition to the existing structure of the Cheese Factory, because the demand was there. I would guess our farm was producing a ton of milk each day.

When the Cheese Factory was humming, if you were coming from the Lower Schoolhouse headed west, as you got closer, the first thing you would encounter was a dreadful odor of rotting cheese whey, which was in the ditch running along the road. At the Cheese Factory, there was a large tank that stood on four legs, which contained the surplus waste products from the cheese production. The whey was run-off liquid from the process of cheese-making and most farmers took the whey home to feed the hogs; we were no exception. I think we carried four old, rusted, cans that were not fit for milk, to fill with the whey product. Upon returning to our farm from the factory, we passed by the hog pens and dumped the whey into a barrel. This provided a hog feed mixture along with ground oats that helped our hogs grow fat.

The wagons and trucks headed to the Cheese Factory would line up with their daily milk to be emptied into a large open metal tank or vat. I remember a solid door on the side of the building with several ribbon-type fly traps hanging around it. Those sticky ribbons were doing their work as there must have been hundreds of flies stuck to them. Interestingly, with the whey nearby, there were almost no flies around. My guess is that they were attracted to the nearby ditch or got caught by the fly traps.

Making the Cheese

Now we step into the cheesemaker’s world. The main big room of the factory was where the master would perform his magic. There were two large metal vats, one empty and one with the fresh daily milk from the farmers that was about to become cheese.

On the ceiling was a maze of pulleys, shafts, and wide leather belts – amazingly, without electricity this entire process was run by steam. There was a motor that sat in the rear of the building or boiler room. Located under the vat with today’s milk, which was about to become cheese, were three or four steam pipes used to circulate the hot water and to heat the milk. The cheese master had a long stirrer that resembled a rake, which he used to carefully stir the milk in the vat, with a thermometer that happily floated in the milk. When the master added the starter mix to the milk, it would form a large glob of cheese, well – almost cheese, as it was surrounded by watery liquid that was called whey. The glob would be either light yellow in color or white, depending on the type of cheese he was making; the smell was intoxicating. The liquid was drained and pumped to the whey tank that was located next to the building. If the tank overflowed, it drained to the ditch. The ditch eventually flowed out the river and into Aunt Jane’s Bay.

A cutter was now placed on top of the vat with the cheese glob and the belts were adjusted. As the cutter was turning, it barely made any sound, but the noise it made reminded me of a hand push lawn mower. The cheese was thrown into the cutter and the leftover resulted in weirdly shaped cheese curd. When you popped it into your mouth, there was a rubbery consistency and a squeak when you chewed it, which was almost heavenly! If the curd did not squeak, it was old and rather tasteless.

The next step was the pressing of the cheese curds to make the large cheese wheels. This process used round steel molds that were in three pieces, which included a top, a bottom, and a middle or center piece that was larger in diameter than the other pieces. Grindstone Island cheese wheels were 6 or 7 inches deep and at least 24 inches in diameter.

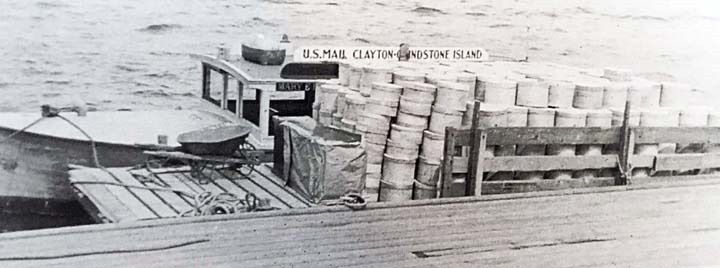

The first step was to lay several layers of cheese cloth in the bottom of the metal wheel to cover the bottom and then fill cheese curd on top of the cheese cloth. Then it was pressed together for at least twelve hours using the cheese press, which was basically a large screw jack. The screw part ran from end to end and as the screw turned, it applied pressure to the last metal mold. When the pressing was completed, the large round of cheese was removed. It was covered and protected by the cheese cloth and when they were stacked on top of each other, they looked like a large roll of Lifesaver candies. The cheesecloth was then stamped with a date, and they were stored for a month or so before they were picked up by wagon, hauled down to the dock, and taken by boat off the island to sell.

The location of the Cheese Factory was in the center of the island, making it convenient for the farmers to bring their milk, but it had no access to the River or a water source. A shallow well was dug at the rear of the building, but it proved to be inadequate for the demand. Eventually, a pipe was installed on my Uncle Leon’s (Leon Dano) farm, down the road to the Cheese Factory, to help fulfill the water needs. However, this pipe was only 1 inch in diameter and was still not sufficient for the needs of the factory.

The glory days of the Cheese Factory ended in 1957, when the factory closed. At this time, many farmers had moved off the island and some of them, like our family, had switched from dairy cows to beef cattle. The building was boarded up and was never used again. The Cheese Factory was sold, but it was only used for storage of some equipment and old cars. The building remains standing on the island, but sadly, due to neglect it resembles an old piece of trash that has been discarded and left to decay.

By Manley L. Rusho