Seeing Shipwrecks Then and Now

by: Dennis McCarthy

Seeing the underwater world in the Thousand Islands is a relatively recent capability for humans. Our eyes rely on light, which water absorbs increasingly with depth, making our view limited to a few feet from the surface.

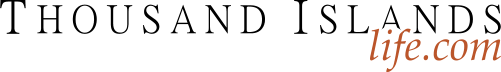

The first deep glimpse under the waters was for a select few with hardhat diving in the nineteenth century, but it was expensive and risky. (Pix 1) Technological breakthroughs in the early 20th century brought diving suits and underwater photography. However, it wasn't until the invention in the 1940s of the modern Self-Contained Underwater Breathing Apparatus (SCUBA) by Captain Jacques-Yves Cousteau that the masses could truly explore what lies beneath the surface.

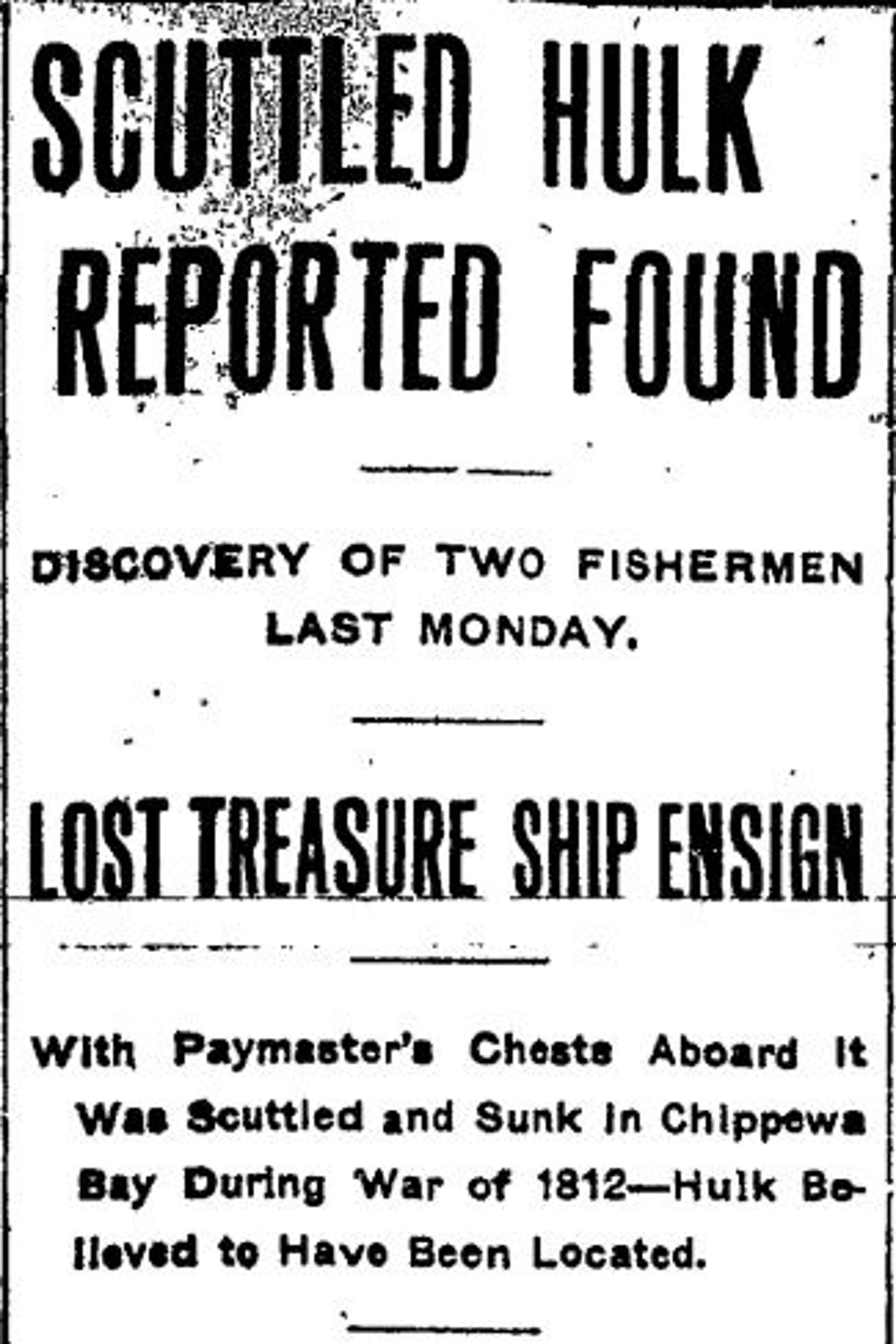

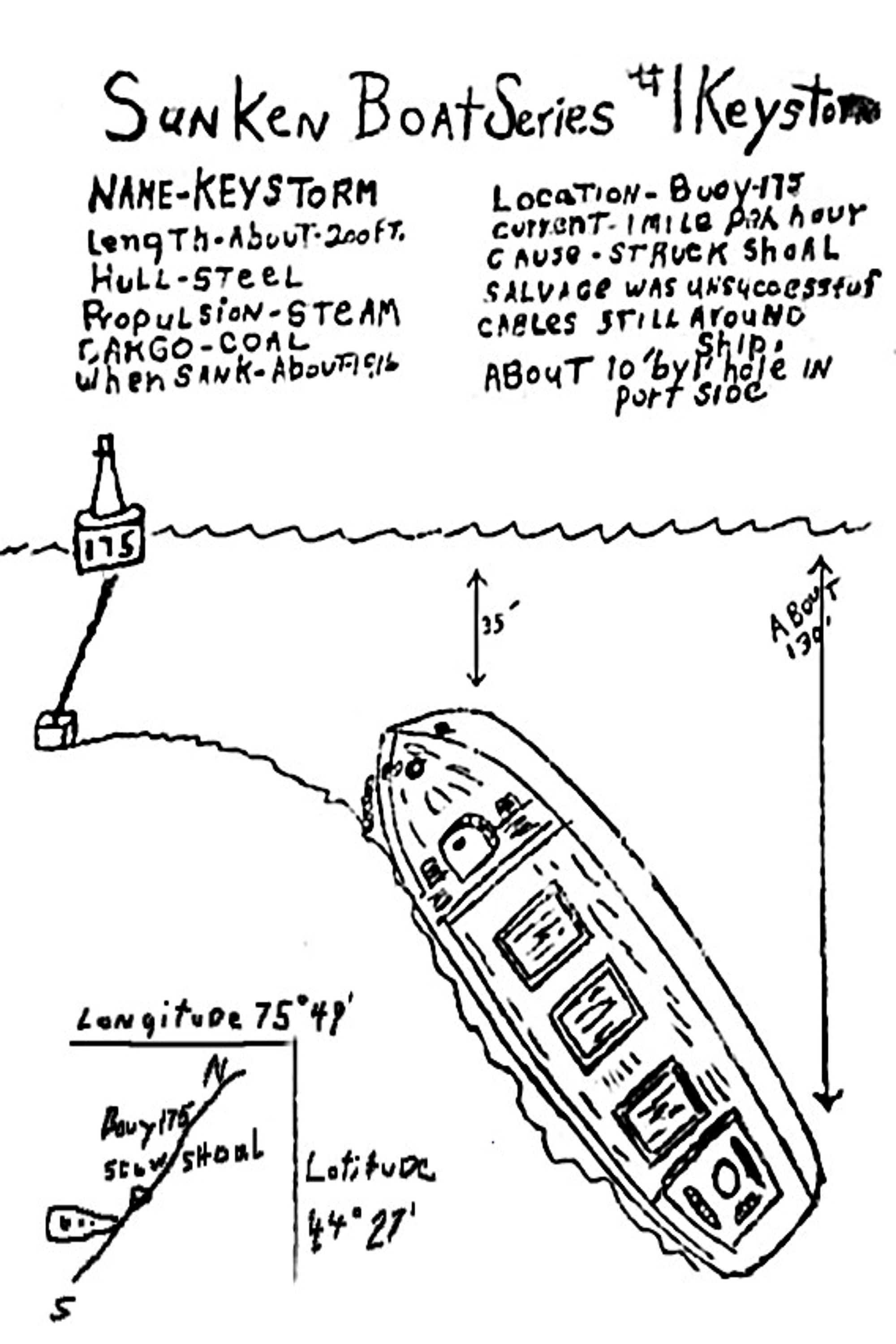

The invention of SCUBA opened the door for a wave of underwater enthusiasts to explore the Thousand Islands. (Pix 2) Initially used for recreational diving, SCUBA quickly became a tool for shipwreck exploration. With a long history of maritime disasters and tales of hidden treasures, the Thousand Islands offered a submerged wonderland for divers to investigate. (Pix 3)

Thousand Islands water visibility in the 1960s at times was like watery green pea soup. (Pix 4) Five feet in summer to maybe 20 in the middle of the winter was considered good. As a diver descended in depth, lights were need to see below 50 feet.

Early diving on shipwrecks required the diver to find the wreck. At first grappling hooks that were used to recover bodies of drowning victims were adapted to shipwreck hunting. They were a simple tool that was effective in snagging objects in deep water or murky conditions. They are easily used from a boat and were commonly used by local search and rescue teams. (Pix 5) Grappling hooks were also very inefficient and potentially damaging to the wrecks. They did not discriminate between sunken trees, rocks, power cables, rock ledges, debris and did not make very good anchors for the dive boat. Sometimes anchors were used instead of Grappling hooks. (Pix 6)

Once on a wreck, the diver was only able to see a small portion of the wreck at a time. To let others know what the wreck looked like divers and dive clubs would make drawings or a sketch of what they thought the wreck looked like. (Pix 7)

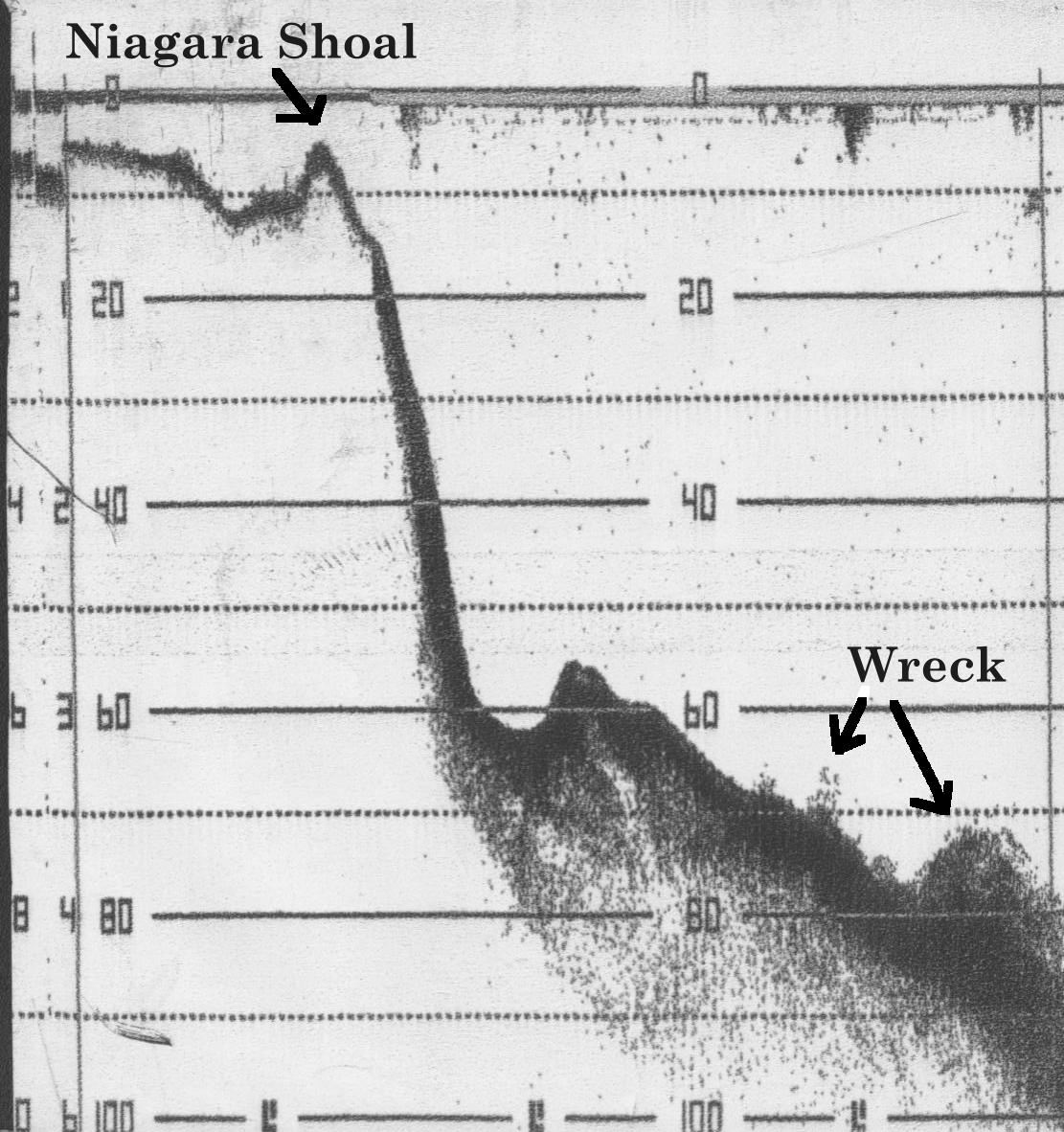

By the 1970s, fish finders that used affordable sonar technology replaced grappling hooks as a way to find shipwrecks. Some units even kept a paper tape image of the bottom. (Pix 8) Also to replace the grappling hook, divers adapted the use of dive planes that could be towed by a boat with a diver holding it. When the diver saw something interesting he would drop off the plane and release a marker buoy. This system was also used by underwater search and rescue teams. (pix 9)

During this period, underwater film cameras such as the Nikonos II Waterproof Underwater 35mm Camera and movie cameras in underwater Housings became affordable for divers. Unfortunately, the clarity of the water and particulates in it did little to produce quality pictures of Thousand Island shipwrecks.

In the 1990s, zebra mussels arrived in the Thousand Islands. These filter feeders, by consuming algae and suspended sediment, dramatically improved water clarity. (Pix 10) This newfound clarity fueled a surge in underwater photography, competing with shipwreck hunting as a popular pastime for divers.

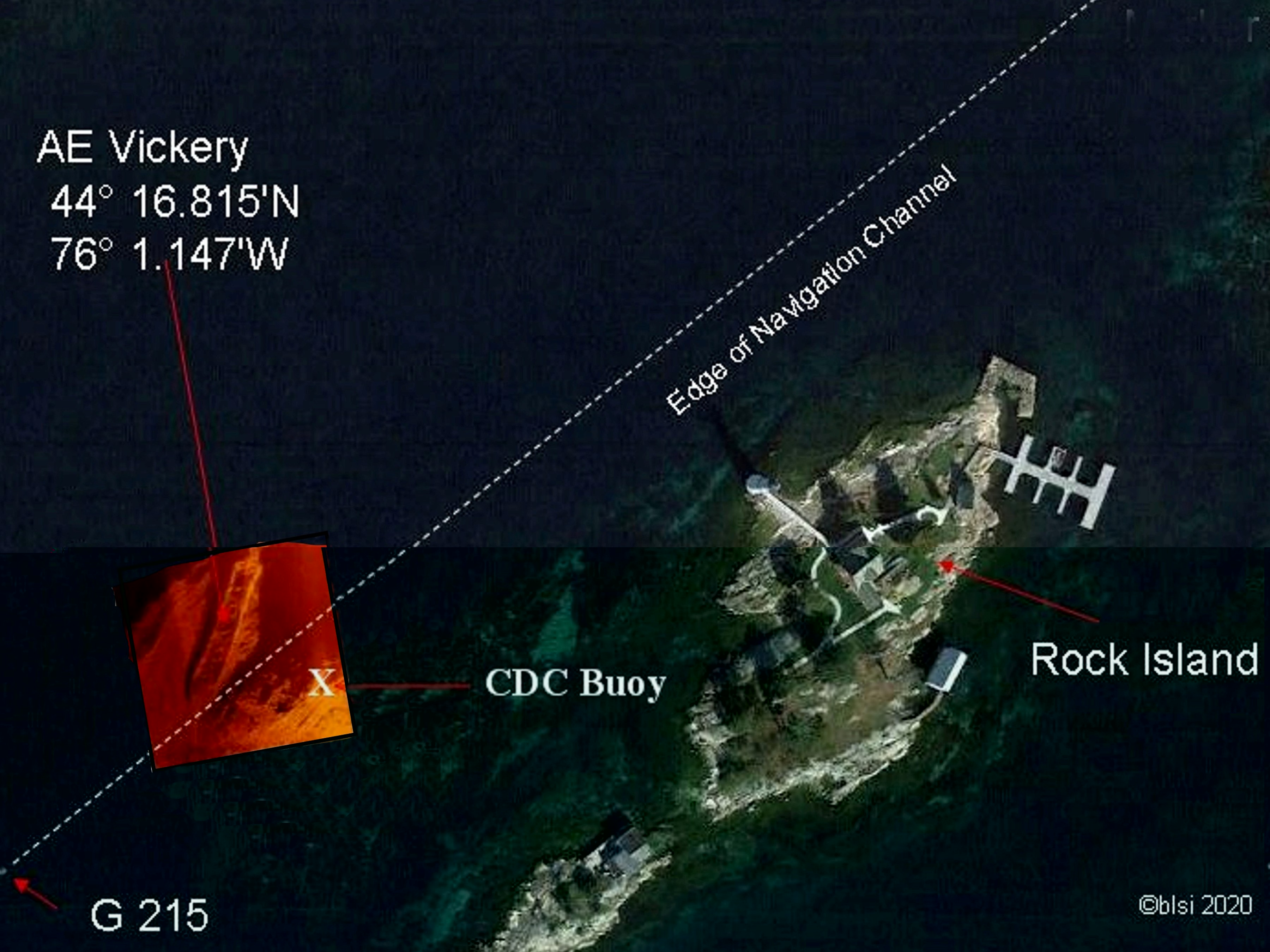

After the millennium, advances and cost reductions of sensing and mapping technology become available to scuba divers. Side-scan sonar, an underwater imaging system used to create detailed pictures of large areas of a water body, became affordable to shipwreck hunters. (Pix 11) Shipwrecks could be viewed in their entirety. Not long afterwards, these images could be combined with GPS and viewed on Google Earth. The entire shipwreck could be seen in relation to where it had sunk. (Pix 12)

The availability of affordable, high-resolution video cameras, like GoPro in the 2010s, made underwater exploration much more accessible. Scuba divers equipped with GoPros could now capture their dives and share them on platforms like YouTube, bringing the wonders of the underwater world to a global audience. This opened a window into the Thousand Islands, allowing both divers and non-divers to virtually explore its aquatic beauty. But this was just the beginning, as more technologies become affordable for the average diver. (Pix 13)

Advances in photo processing, remote sensing, underwater robots, and AI mean that viewing underwater is now technology driven. Within the last 10 years, technology has advanced the ability of people to see what is under the water in a way that no generation before has been able to do. As with any technology driven process, it improves at an exponential rate.

The following are some of the new ways to see shipwrecks, which now are being used by divers and shipwreck explores to see and record what is under the waters of the Thousand Islands.

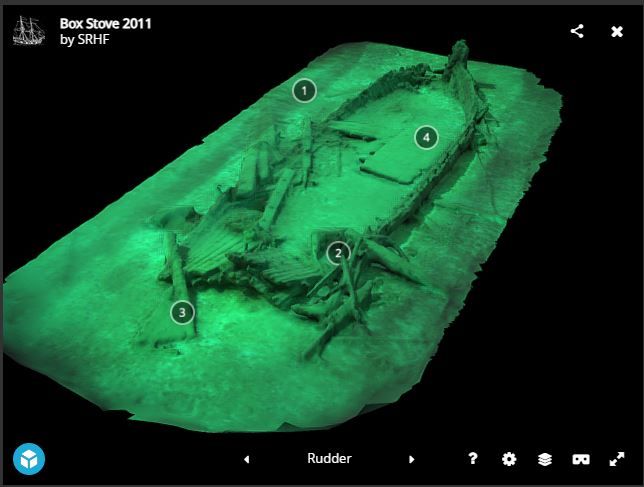

Photogrammetry is a way of creating 3D model of a shipwreck from a series of photographs or a video. It allows the diver to take a bunch of pictures from different angles, and then using the software to stitch those pictures together into a digital 3D model. When these 3D models are hosted on the internet, they provide highly realistic VR experiences, allowing you to feel immersed in a virtual space. It’s almost the same as what a diver would see. (Pix 14)

Multi-beam sonar, a type of underwater imaging system used to map the seafloor and detect objects in the water, is now affordable for shipwreck hunters. Unlike single-beam sonar, which uses one beam to create a single profile of the seafloor directly below the instrument, multi-beam sonar transmits multiple beams at once in a fan-shaped pattern. This allows it to cover a much wider swath of the seafloor, creating a more detailed and accurate picture.

Autonomous Underwater Vehicles (AUVs) and underwater drones (Pix 16) collect data and images without human intervention. This allows for longer missions and exploration of dangerous environments. Not just for scuba divers, these new technologies are even being used by the fishing community. Most modern bass fishing boats have better electronics than Jacques Cousteau had on the Calypso when he passed through the Thousand Island and visited Lake Ontario in 1980. (Pix 15)

One result of the new ways to see shipwrecks in the Thousand Island is that they are generating concern that these wooden shipwrecks are rapidly deteriorating from the natural effects caused by the same organisms that are now allowing them to be seen.

Divers who saw the wrecks pre-zebra mussel remember original wood of 150-year-old ships still being discernible. Now that the wrecks can be seen clearly, they appear to be disintegrating at a faster rate than we have ever seen previously.

These new technologies will allow pictures and 3D models of shipwrecks taken over time become a valuable tool to determine if the wrecks are deteriorating. By comparing 3D models created at different points in time, researchers can identify areas of significant change in the shipwreck's structure. This can help differentiate between natural deterioration and damage caused by human activity like looting or salvage.

For more reading see:

· Thousand Islands 3D Shipwrecks

· 3DShipwrecks.org

· Advanced Navigation

· Drone Revolution (advancednavigation.com)

· Inside the battle to preserve the underwater ghosts of Ontario's Great Lakes | CBC News

By Dennis McCarthy

Dennis R. McCarthy lives in Cape Vincent, NY, along with his wife Kathi. He is a graduate of the Rochester Institute of Technology, with a degree in Electrical Engineering. A certified scuba diver for over 50 years, he made his first dive in 1971. He is a co-founder (1994) and current director of the St Lawrence Historical Foundation Inc. and current president of the Clayton Diving Club. Dennis and Kathi are board members of Cape Vincent Historical Museum and past members of the Advisory Council for the Proposed NOAA Lake Ontario Sanctuary.