Sea Smoke Rising, A River Odyssey

by: Raymond S. Pfeiffer

Rare are the times when immersion in fog helps one to see things clearly! In more than seven decades of summers and many springs and falls on The River, I had never been unable to navigate successfully from either Clayton or Gananoque to my homes on either Hickory Island, Grindstone, or The Punts. I have crossed that water in huge storms, in fog, in traditional St. Lawrence sailing skiffs, in punts and in little kayaks. I have gone forth in howling gales, in cosmic darkness, and used compass bearings to navigate through miles of fog. I had even seen fog move aside in the wee hours of the morning, just when I needed it to do so. I have had no real plans for what to do or where to stay if something prevented a desired crossing.

On Thursday evening, October 3, 2019, my dear friend, JBJ, accompanied me across the River in late afternoon to the Thousand Islands Playhouse to see the play, “The New Canadian Curling Club.” It was a show that we both enjoyed greatly, due to the wit of its script and the talent of its actors and creative stage crew. River conditions seemed normal that afternoon, with a northeast wind blowing up the River, but at a moderate clip.

It was at the intermission, when I went out on the Playhouse deck, that I discovered considerable fog on the River. I could not see our lighthouse light from the theater, which is unusual. I thought that, after the show, I might need to use my GPS to return to our little island at the head of the Lake Fleet Group. But I did not mention it to JBJ, who had not noticed the fog.

In most foggy conditions, it is prudent to stay in town, a change of little significance to one’s plans. However, for us, the return home to The Punts was important. We both had a real desire to awaken to what, in our minds, is one of the most beautiful island homes in all the world. And it is our home, five kilometers from shore, in open water, where we want to be, and love being, in all the moods of the River.

There was another motive at work here, and it is one that JBJ had sensed but did not probe. That is the challenge of crossing that water to our sanctuary. It is undeniably connected to my own ego. I love a challenge, if there are reasonable odds of success. I had both the skills and the understanding of River risk and of the mistakes made by some, even tragically, in their travels upon the waters. I was not one to avoid the adventure.

Fog is, of course, the great enemy of navigators, having caused innumerable crashes and shipwrecks all across the world. The wise and cautious will always say that it is best avoided by craft of all kinds. Fog at night on the water poses among the most extreme dangers.

On the other hand, GPS navigation has become precise and reliable, and I had a two-year-old Humminbird unit on board. I had put in waypoints for the trip to and from The Punts Islands to Gananoque, Ontario, and even tested them out one day early in the summer. I had confidence.

Our boat that night was the Grape-Nut Two, a nineteen-foot Grady White fishing boat with a windshield and low canvas top, built twenty-five years earlier and powered by a 150-horsepower Yamaha, four-stroke outboard from 2004. I had bought them six years earlier, having known their first owner, Bill Shirley, and I maintained them well, and considered them reliable. I felt ready for our trip home.

Down at the dock, it was damp, chilly, and oppressive, and we felt the low pressure in the area. We had some trepidation, but not enough to cause discussion. We cast off and headed out into the fog, the darkness, and the blindness, guided only by our GPS. Past the first waypoint, we could see nothing except the milky glow of Gananoque's lights behind us. The engine turning a little more than idling speed, at 1100 rpms, I steered for the second waypoint between Hay and Cobb Island.

Past the second waypoint, we could see that we were leaving the cut between Hay Island and Cobb. It is a gap of over a kilometer, and I could see on the split screen on my GPS navigator that the depth of the water was increasing, as it went from seven feet to twenty, and deeper. We were heading toward the one-hundred-foot-deep Middle Canadian Channel where there is a huge flow of water moving powerfully downstream at about four miles per hour or nearly six kph. I was reassured that we were on the right course, our waypoints placed well out in the middle of open water.

Now, heading into the abyss, I had a feeling of apprehension, and of a little fear, wholly unable to see anything beyond the boat. Yet, upon reflection, I felt confident that even if we did hit something, such as a shoal or an island, or some floating obstruction, or jetsam, that our slow speed would prevent significant injury, and might not even puncture the strong, hand-laid fiberglass hull. We hummed at low speed across this big River, and we moved on and on, very slowly, knowing our location only by seeing the brightly lit, almost glaring representation on our GPS screen.

As we progressed out past Hay Island, evidence of the wind became more noticeable, making it impossible to steer a straight course, as we were blown about, and repeatedly knocked off course by waves that increased in size as we went. They probably peaked at about two feet high as we came within a kilometer of the island.

It was then that we could see, up high above the water, the familiar, flashing green light of the beacon on one of our tiny islands. Although we were heading in that direction, I was careful not to go directly to that light. It stands on rock about five feet above the River level, and about two meters from the water’s edge. It extends upward about ten meters, visible from the water some two hundred and seventy degrees from southeast to northwest. The question that struck us was: “How could we see it with such thick fog all around us?"

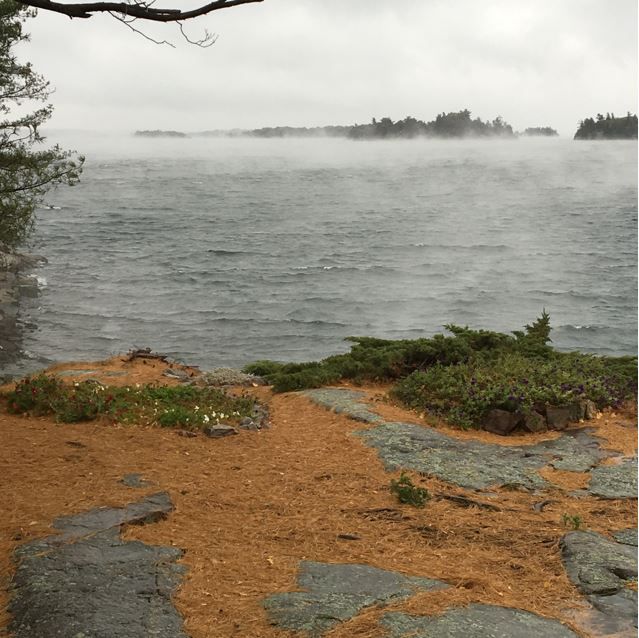

We were subject to a phenomenon with a variety of names. It is a kind of fog, sometimes called sea smoke, frost smoke, or steam fog which most commonly forms in the fall and the spring. It comes when cold, humid air crosses water that is warmer, making the fog appear to rise up from the water. Up-wind, at the water’s edge, the fog is light and thin. But farther out on the water, say a kilometer or more, it can be as thick as traditional “pea soup.” Where we were, some six kilometers from its up-wind shore, it was visually impenetrable at less than a boat-length.

Thick as it can be, this fog did not extend upward very far. I would estimate that most of it rose up only four meters high. Had our boat been bigger, and we sitting farther up, we could have seen out over it to distinguish tree lines on islands in the area. However, we were down in it, and could see no tree lines and no shores during our entire journey.

We neared our little islands with the flashing green beacon somewhere above us, and we became worried, as the waves had increased, and we were bobbing like a cork, the lighthouse going up and down in our visual field, and the boat weaving about among the waves. It was disorienting, and troublesome, as the lighthouse seemed to move along our starboard side, becoming almost abaft the beam. Yet, we did not know how far we were from the lighthouse island or the dock.

The question in both of our minds was how it could be possible for us to see the shore and the dock. Our GPS was not tuned to such fine distances for which it was trustworthy in close quarters, accurate to less than two meters. Our docks had solar-powered lights on them, but we could not see any through the fog. We needed to avoid that rocky shore, the shoals around it, and see the dock to be able to land at it. We knew we were close to the beacon and the shore, but not how close.

I shined a searchlight into the fog, which immediately convinced me that we could not see far enough to be able to land. And as I did so, the wind and waves swung the boat around to the east, and I felt dizzyed by it, and disoriented. I had been looking up at the beacon, and now looked down at the screen, as we swung around farther from the east to the north. The visual transition from seeing the green light in darkness, to the bright GPS screen, to the searchlight into nothingness was dizzying, and the moving of the boat worsened the sensation. I felt singularly unsure just how far out we were from the shore, from some nearby shoals, and from shipwreck.

I felt serious worry as JBJ asked me, “What do we do now?” I chose the only reasonable answer that I could, and said “We’re going back.” But the swinging of the boat, together with my sense of disorientation, caused a sense of fear that I rarely felt on these waters. Fortunately, it did not flummox me, or prevent my doing what was clearly the right move: I allowed us to swing farther, until we had exactly reversed the course we took to arrive. And then, both of us seriously frightened, we headed back, having not touched anything but this beautiful, dark, soft water.

We went to our waypoints, and then close to the Gananoque shore, where the fog was lighter, and we could see our way to the marina. When we docked, we both agreed that we were still shaking from the stress of it all.

In no condition to ask friends or family for a place to stay, after midnight, we resolved to find a room for the night, and relax at a local pub. The first motel we stopped at was full, and the first pub we approached had closed. We found one open not far away, and then found ourselves in the company of the cast and crew of the play we had so enjoyed! We told them our tale, and they were fascinated. They mentioned that it would be really fun to go out to visit.

We discussed the possibility of such a visit, and then followed up with a phone call that brought a very positive response from our theater friends. It was the following Friday that we picked them up, took them on a tour of the islands, and brought them out for lunch with us on the island. We had a wonderful and memorable time from it all, having pulled out vivid and joyful memories from the open jaws of disaster.

By Raymond Pfeiffer, The Punts, Lake Fleet

Raymond Pfeiffer is a Professor of Philosophy, Emeritus, from Delta College in Michigan, author of three books and twenty scholarly articles. He is a lifelong River Rat, occupant and caretaker of The Punts Islands, a long-time sailor and maintainer of St. Lawrence skiffs, a fisherman and boater who has lived on Hickory Island, Grindstone Island, and The Punts.

Editor's Note: There are many times when we experience a crossing that makes us uncomfortable. After stories like Raymond's sink in... I think it is high time we not throw caution to the wind and we should make other arrangements. I know I will (I promise).