From Out of the Twilight - a Ray of Hope

by: Lynn E. McElfresh

In mid-July, Clayton P. O. mailboat driver, Brian Parker, delivered exciting news with the bag of mail. “Have you seen the comet?” he asked. Brian, a resident of Grindstone Island, excitedly told my husband, Grenell’s postmaster, where to look in the sky to see this awesome sight.

The last time we went comet hunting was in 1986. Halley’s Comet was making its first appearance since 1910. Because we lived near St. Louis, it was tough to find a spot dark enough for comet viewing. Despite our best efforts, all we accomplished was missing precious sleep. After my Halley’s Comet experience — or rather non-experience — I was dubious.

In July, the sun sets shortly before nine, but the islands aren’t plunged instantly into darkness. It seems to take forever for the sky to cycle through stages of twilight until at last — two hours after the sun has dipped behind Murray Isle — the stars begin to pop out.

Slightly above the horizon, seven fingers down from the lowest star in the Big Dipper, was a smudge that sparkled like fairy dust. I focused the binoculars on it. An incredible sight came into focus. We sat mesmerized, gazing at the sky above Murray Isle.

The next day, I searched for this comet’s name and learned that Neowise is the brightest comet visible in the northern hemisphere since Comet Hale-Bopp in 1997. I thought Neowise was a pretty cool name, perhaps suggesting that this comet was ushering in an age of “new wisdom.” I was a tad disappointed to learn that the comet was named for the telescope program that discovered it in March. (Secretly, I’ll cling to the hope of new wisdom.)

The event reminded me of a pair of newspaper articles I'd come across while researching my first Thousand Island Series book, Grenell 1881. The first article appeared in 1919, the second in 1923. Both described a comet event viewed from Round Island in September 1881. Both had the title, "Famous Red Morning at the River When Air Had a Carmine Hue." The subtitle read, "Earth Passes Through the Tail of a Comet — Summer Resident's Panic-Stricken, Thinking World Was Coming to an End."

The Observer wrote both accounts in Clayton On-the-St. Lawrence. At dawn on September 2, 1881, a cook broke the autumnal quiet by yelling, "Get up, everybody! The world's on fire! The end of all things has come."

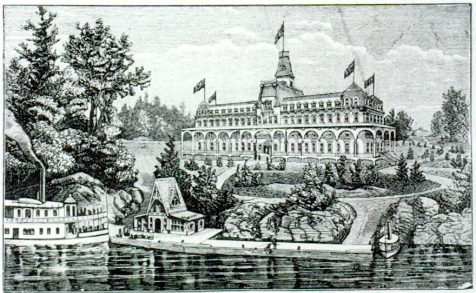

The summer crowd had left the Round Island Hotel, as it was late in the season. Those who remained made their way to the windows and looked out. The Observer suggested that perhaps they thought they were looking through a stained glass window, for the world beyond the window — grass, trees, water, and buildings — was colored with a bright red hue.

Seeing the red world beyond the windowpane struck the hotel guests with the same thought that had awakened them — the world was coming to an end. Pandemonium erupted as Hotel guests hastily packed trunks and dragged them down the stairs with such force that they tore great splinters from the steps' edges. The J. F. Maynard, the first steamer of the morning, was packed with fleeing guests.

Meanwhile, back at the hotel, all preparations for breakfast had been abandoned. The female employees were near hysteria — wailing, crying, and saying prayers. Reportedly a fishing guide came to pick up the fish lunch for an outing to find an hysterical woman in the kitchen storeroom. When she asked if he still planned to fish, he reportedly quipped, “Why, yes, we’re going a fishin’; that is, if we can git away before the grand catapulsion comes, which we hope will wait a while, fer we’ve got all the stuff to make a bully fishchowder, an’ we would rather go aloft to visit the people on the moon with full stomicks.”

Reportedly the sky glowed red for several hours while river guests and residents cowered and prayed. Eventually, around noon, the atmosphere changed to a brilliant orange, then faded to yellow and slowly returned to a familiar blue sky.

The 1923 account reported that in the weeks preceding the red morning, people on Round Island had reported seeing an immense comet in the northwestern sky just above the treetops of Bluff Island. Purportedly, the comet's head was centered above Bluff Island while the tail extended in a northeasterly direction well beyond the end of Maple Island, nearly a mile away. After the red morning, the comet was no longer visible in the night sky.

This description of the comet and the red morning wowed me and fired my imagination. I thought it might make a thrilling conclusion to Grenell 1881. So I dug in to find out more about this giant comet of September 1881. I was disappointed not to find any other accounts of this celestial event, leaving me to doubt if it happened. I found mention of The Great Comet of 1882, a worldwide event, so perhaps The Observer was a year off. Unsure, I decided not to include the red morning in Grenell 1881.

We spent several nights on the dock gazing up at Neowise — still hoping for that new wisdom. I was disappointed when we viewed the Perseids meteor shower in mid-August that I couldn’t see Neowise. It had disappeared below the horizon.

We've seen wondrous sights from the end of our dock: satellites, the International Space Station, planets, constellations, a lunar eclipse, and northern lights. Now I can add to that list a comet. Staring up at the maze of stars above helps put everything into perspective. The Universe is vast and miraculous. We are only a tiny part of something much, much larger. So lie back, look up, and get lost in the stars.

By Lynn E. McElfresh

Lynn came to Grenell Island for the first time to meet her fiancé’s family, in 1975. She became part of the family, and the island became part of her life. Lynn and her husband, Gary, spend their summers in the Thousand Islands and their winters in Dunedin, Florida. To see all of Lynn’s island experiences, search TI Life under Lynn McElfresh.

Lynn has written two novels in a series of nine novels about life in the Islands from 1883 t0 the 1960s. The third book is in the cover design stage and will be available soon.

See All About Lynn McElfresh & Her Books, in this issue, September, 2020.