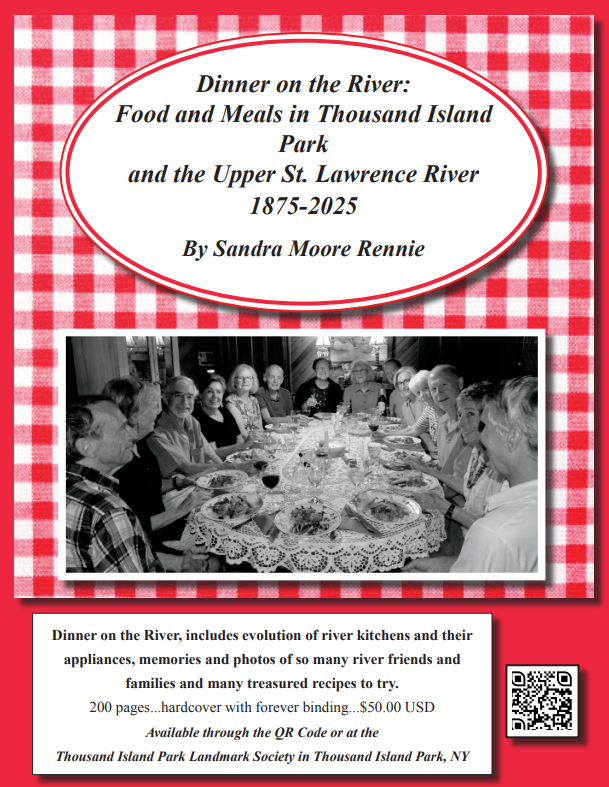

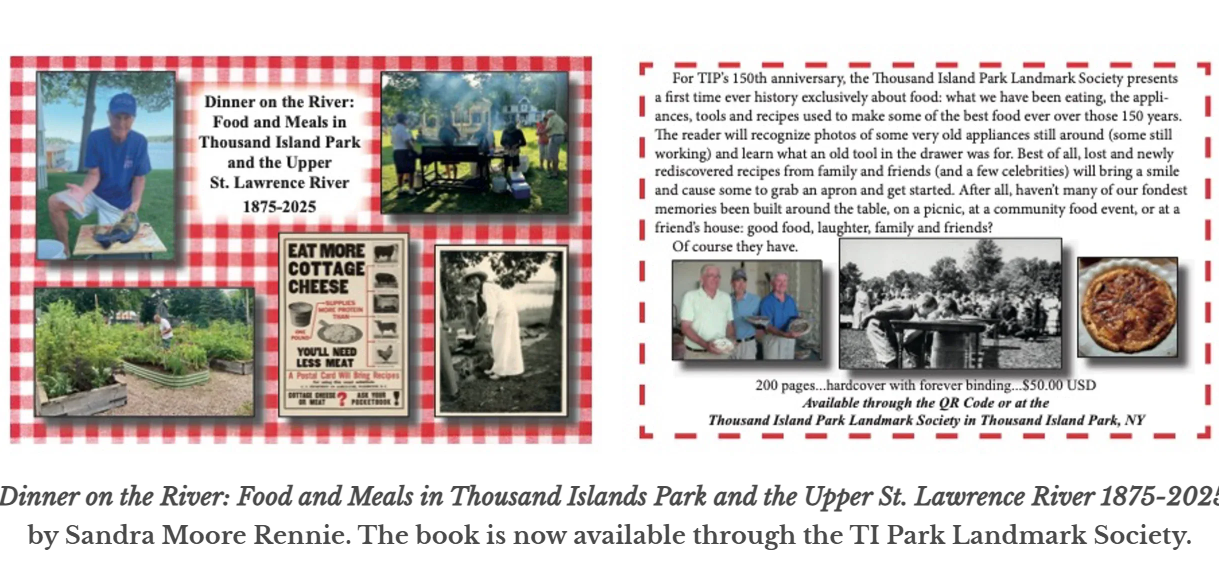

Food and Meals on the Upper St. Lawrence - Part 2: 1925-2000

by: Sandra Moore Rennie

[Editor's Note: How lucky are we? Not only do we have the opportunity to learn about this special collection of recipes, but the author is sharing the Who, What, Where, When and Why! Yes, very lucky indeed.]

A 150-Year History of Food and Meals on the Upper St. Lawrence - Part 2: 1925-2000

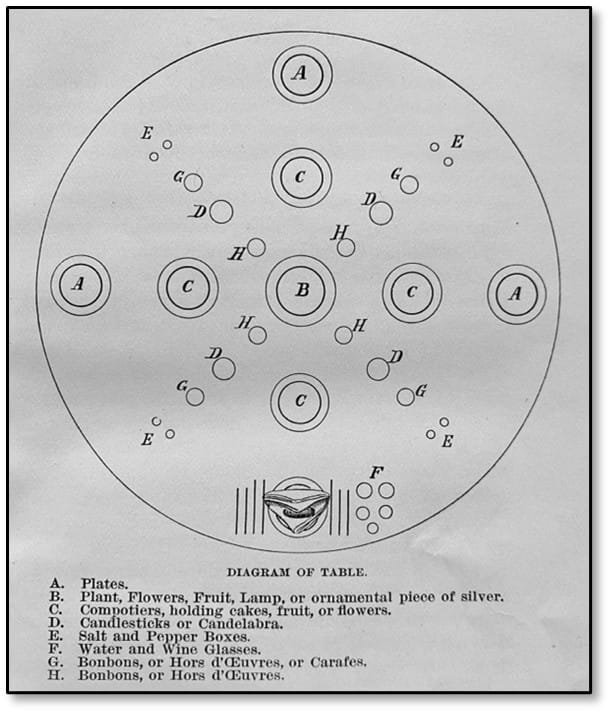

The effects of Victorian sensibilities surrounding food—attention to detail, punctuality, many special rules around table service (many single purpose eating utensils and plates and glasses)—continued well into the 20th century. Very gradually, what we ate, and even where we ate it, changed. Formal, multi-course menus gave way to casually presented meals with three courses at most—soup or salad, entrée, and dessert. The default dessert was no longer an elaborate pudding or an ice. The new stoves made more delicate recipes, like baking a reliably successful cake, easier. Appetizers appeared around 1950, gradually becoming an important start to the dinner, increasing in variety and served away from the dining table—in the living room, on the porch, out on the lawn, even on the boat. Tiny Victorian portions of one or two bites per course expanded to offering seconds of the entire course.

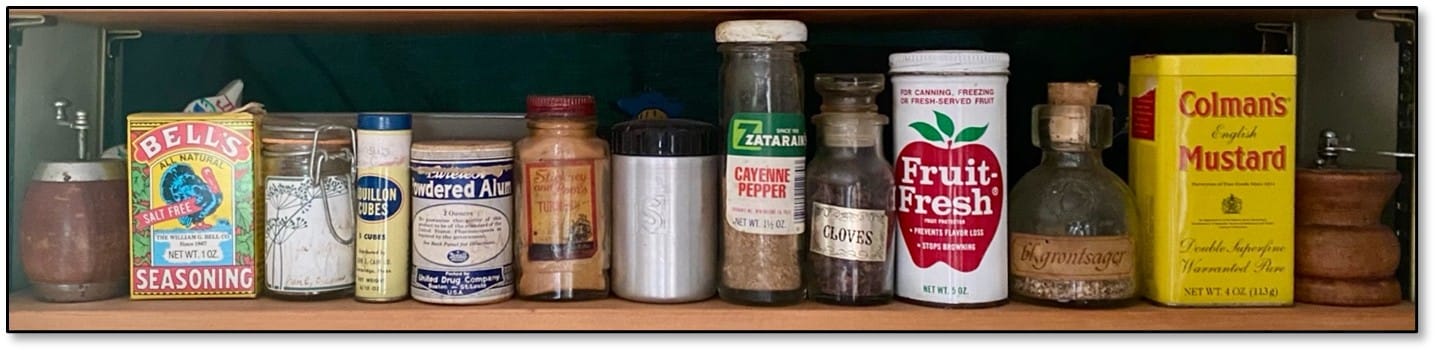

During the Great Depression in the 1930s, changes reflected contracting economic circumstances. Depression cooking was simpler; less meat, really less everything. One recipe in the book is for oatmeal soup, essentially watered down oatmeal that was served as a first course at dinner during this period. Advice from a 1930’s era cookbook counseled “Don’t give sympathy when food is wanted,” and “Every child is entitled to at least three well prepared, attractive, nourishing, warm meals a day.” Home canning increased dramatically. Some had canned before—mostly jams and jellies—but now canning included more fruits and vegetables. The local newspapers gave guidance for the first time to home gardeners seeking to save money on meals. Birdseye produced high quality frozen food that he based on flash freezing learned from Native peoples in the far North. His first products were peas and spinach.

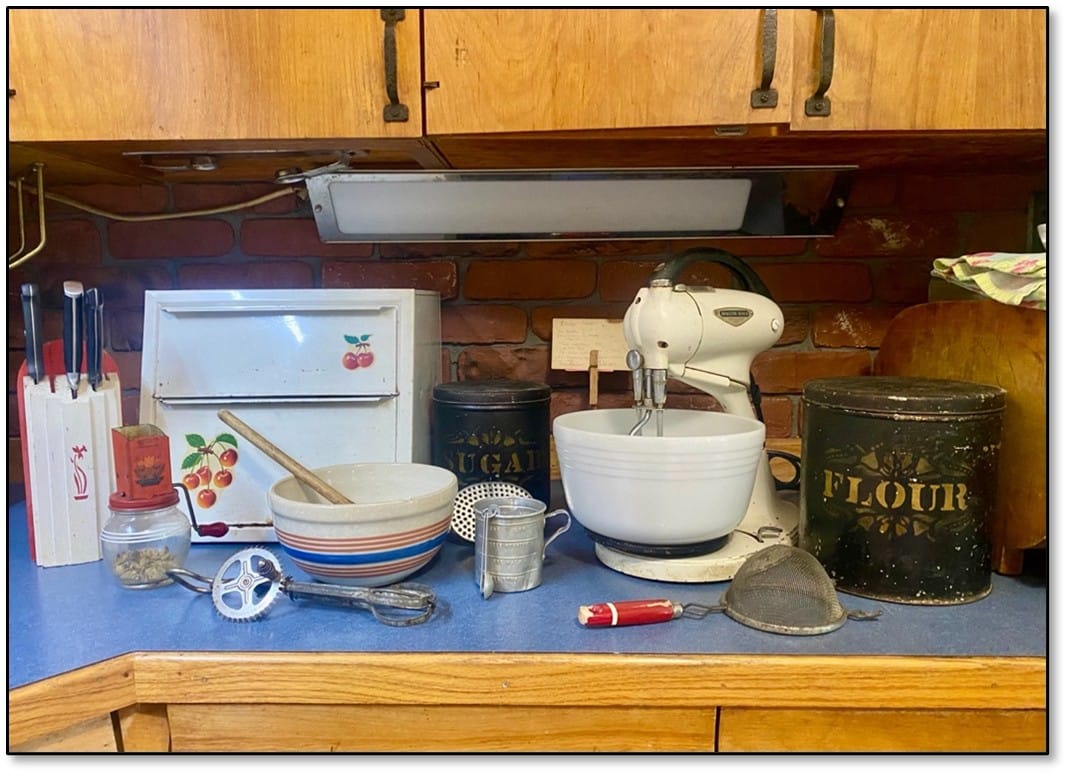

During World War II, married women worked in numbers never before seen. Those women didn’t have the 6 hours per day their grandmothers had spent in the kitchen to prepare meals. WWII cooks benefited from new kinds of appliances: stoves with thermostats, modern ice boxes, and some even had early refrigerators with little freezers within. Specialty appliances had become rapidly available: Mixmaster, electric kettle, pop-up toaster in 1930; Waring blender in 1937.

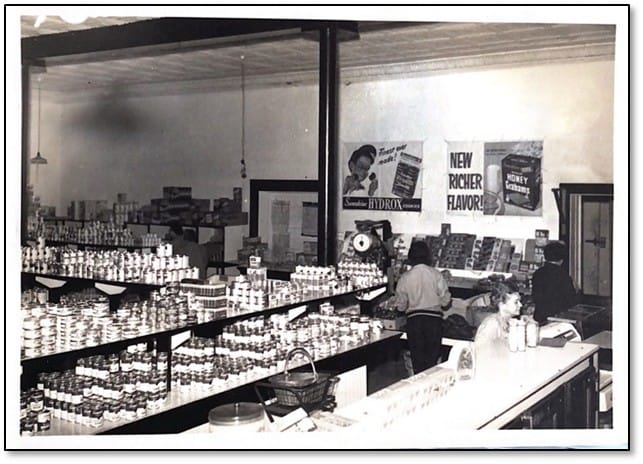

In the post WWII period, large food markets began displacing the smaller stores and farm stands; they had many times more ingredients available plus essentials like sugar, oil, and butter that had been rationed during the war. The post war economic boom had left families better off and able to spend more for conveniences. They were also mighty tired of having done without basics during the war.

Spice Islands initiated a middle step on the way to factory processing. It sold packets of flavorings that included a glass container for mixing with oil and vinegar to make a salad dressing. Pre-packaged foods like Hamburger Helper, Jello pudding, and more made meal preparation faster and easier. The first packaged cake mix appeared in 1949.

Starting in the 1960s, experimentation and open-mindedness expanded into trying ethnic recipes not even imagined before. Among the ethnic recipes in the book are Italian (Lasagne), German (Sauerbraten), Polish (Hunter’s Stew), and Japanese (Chicken Teriyaki).

Our palates were expanding; but there was a problem. Though our imperfect understanding of the Victorians led us to believe they ate way too much, and although we ate fewer courses than they did, we were actually eating more food and we were gaining weight. The highly processed foods were also having an effect—sugared cereals, between meal snacks, very large sodas, highly salted chips, and so on. We didn’t always know what was in those packaged convenience foods because in the ‘60s there were no labels listing preservatives, artificial colors, and flavors. Not surprisingly, all kinds of diets appeared.

By the 80s, there was a return to cooking “from scratch” for some that included homemade yogurt and complicated French dishes. Simultaneously, more pre-packaged foods appeared—McNuggets, Pop Tarts, and lots more. Some of the pre-packaged foods were simple: Mr. Birdseye had expanded his original frozen food packages to include 18 cuts of meat plus fruit, berries, Bluepoint oysters, fish filets, as well as the original peas and spinach. Basically, two meal preparation strategies were coming into place: save time with pre-packaged or focus on healthy eating by using fresh ingredients. Many did some of each.

The last years of the 20th century expanded the choices of both fresh ingredients and packaged meals, leaving the cook with abundant choices. The reader of the book will find recipes for both strategies. Nevertheless, some constants endured among ingredients used: fish from the River, maple syrup, and all things from milk: so many cheeses, cream, and our long time favorite, ice cream.

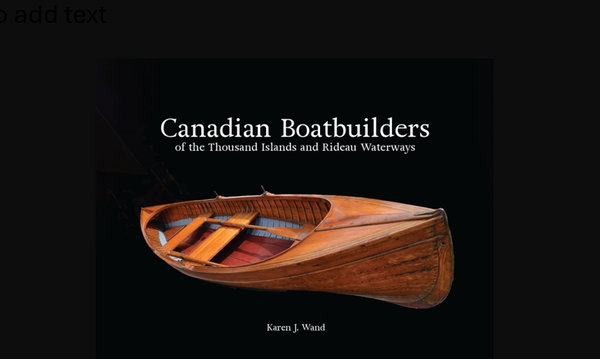

The final part of the story of Food and Meals on the St. Lawrence—that focuses on 2000 – 2025—will appear in the August 2025 issue. For more information about the book or to purchase it, please go to: thousandislandparklandmarksociety.org.

By Sandra Moore Rennie

Sandra Rennie summers in Thousand Island Park, where her husband’s family set down roots in the early 20th century. She has contributed to several anthologies on living well and is working on a book on her life in gardens. She started an early multi-disciplinary environmental consulting firm, served as a senior executive at the US Dept. of Energy in Washington, D.C. and for 20 years as a mediator of multi-party, high stakes environmental disputes around the US.