Episode I: Roscoe Fish Goes "Boying"!

by: Sarah Bodine

[Note: See Introduction: Roscoe Fish Stories, January 2024]

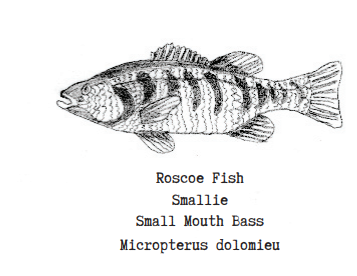

The World of Roscoe Fish

Every morning, at dawn, as the sun’s first rays came streaking through the cool, green water above his cave beneath Pine Island, Roscoe Fish slid out of his cozy seaweed bed. Fish live by light and shadow, not by time as humans measure it. So, the sunrise, no matter when, was his signal to wake up. His waking routine was always the same: first, he stretched his small pectoral fins forward to push water by his eyes – Roscoe slept with his eyes open, as do most fish, because they have no eyelids. Splashing water by his eyeballs refreshed them so he could see more clearly.

Next, he worked his tail back and forth, pushing himself forward onto the smooth, level rock just inside the mouth of the cave. This is where he practiced his spin-ups. Spin-ups are to fish what push-ups are to humans.

To start, Roscoe lay on one side and then quickly twirled around, sliding his belly up and down against the rock and making a stream of small bubbles. After a set of spin-ups – about l0 flips – now fully awake – he shook himself all over and glided back inside the cave.

To prepare himself for the day’s swim, he pressed his scales along a vertical rubbing wall to smooth down the rough ones that had jutted out all which way during the spin-ups. Then he plunged under an overhead nozzle that spit out refreshing seaweed essence, a kind-of gooey glide wax. Shivering and twisting all around, Roscoe made sure that every scale got coated. Next, he floated over to the corner where a tangle of roots grew down into the water from a tree on the island above and chomped down on a section of root. By sliding his jaw back and forth he could polish his tiny interior teeth. Finally, he checked himself by peering up at his reflection in the under surface of the water.

Ready for his morning swim, Roscoe zoomed out of his cave and, pushing off with his wide tail fin, burst out of the water, delighting in this morning ritual. His circular splash threw out a thousand tiny water droplets that cascaded like diamonds down on the placid surface of the early-morning River.

Roscoe was a champion swimmer. As a small fry, he had learned at Fish School how to glide quietly through the water by aiming his body totally straight. Early on he mastered the backstroke, slicing the water with his spiny dorsal fin, and the deep dive, made with a quick swoosh of his tail fin. Practicing jumps and dives was essential for escaping dangers in the unpredictable River.

“Remember that your vertebra, or back bone, is in the middle of your body and is not as flexible as your fins,” the ancient rainbow trout who ran the school had instructed. “To turn direction in a hurry, don’t flap your fins but use them as rudders.”

As he broke through the surface into the clear, fresh air, Roscoe remembered to keep his mouth open just in case he might snag a tasty mayfly for a pre-breakfast snack. He was always voracious after his exercise routine, and this morning was no exception. After a leap or two, he zigzagged down past the mouth of his cave and headed for his favorite eating spot – the Frost Diner.

The Frost Diner

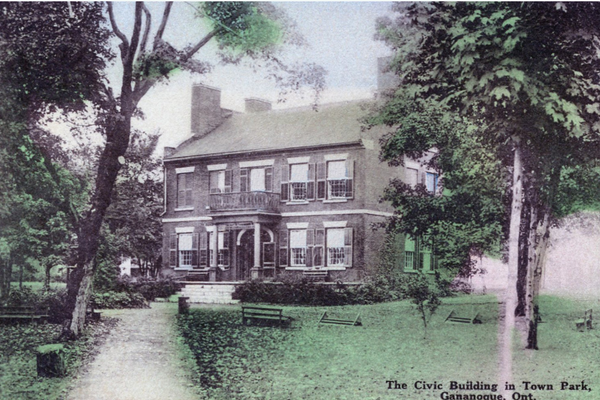

The Frost Diner lay deep down under water. This fish-feeding hole was located in the hull of a big old steamship that lay just off the Canadian mainland, near a village called Rockport. In the last century, such ships had taken tourists on cruises around the Thousand Islands. Once, during a violent storm, this ship lost its way in the high seas and rammed into the boulder that marked Rockport’s harbor. With a loud crack that was heard all over town, the boulder punched a gaping hole in the wooden bow. The boat drifted backwards, filling with water as she sank, deeper and deeper, into the cool, dark waters of the Canadian channel.

The lifeboats had been lowered, and all the passengers were saved and taken ashore, but the ship came to rest on bottom, 100-feet down, and nestled upright in the soft, muddy riverbed. The ship lay so deep, and she was so heavy and waterlogged, that she was never recovered.

Since then, long docks had been built out from the boulder at the head of Rockport’s harbor. Summer people moored their boats at these docks while their kids walked over to Eleanor Collins’s store for ice-cream cones. When they came back with their cones, they climbed up on the boulder. Naturally, bits of gooey cone would fall into the water, and the dripping cones attracted schools of small river perch. The fish could look up at the kids above, but the kids could not see them down below, because the deep water was very dark and green. For fish, this made for an ideal feeding place.

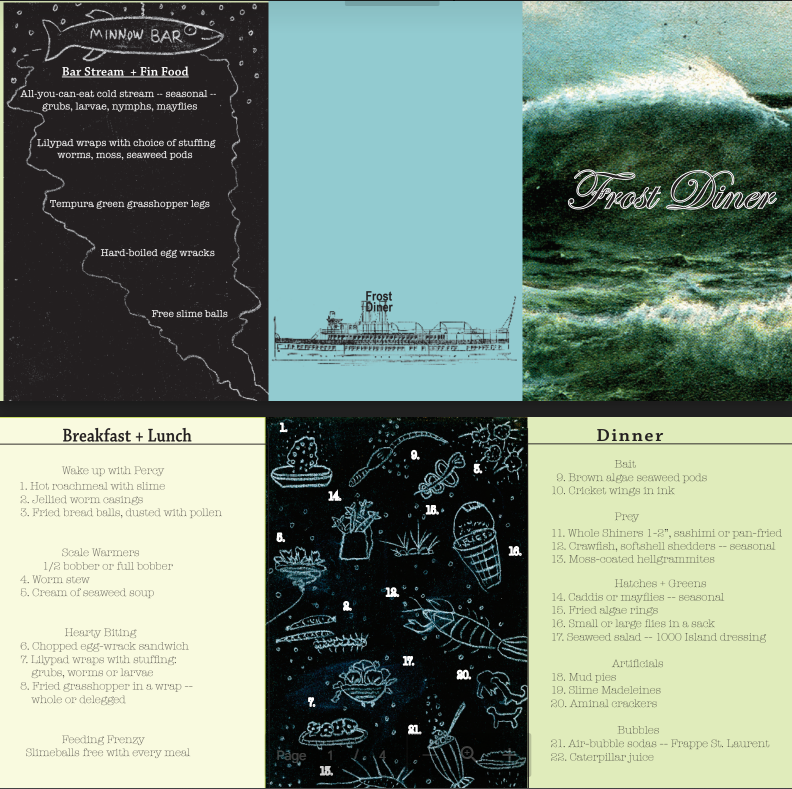

Not long ago a cunning old perch – whom everyone called Percy – had discovered the wreck of the old steamship just off the boulder. Because fish were used to going there to feed, he thought the hull would be perfect for a diner. Immediately, the Frost Diner became a popular haunt. Roscoe especially liked to have his breakfast there, on the early side, when the River was quiet. On this particular morning, after his brisk swim across the channel, Roscoe noticed that few fish were around and decided it was safe to swim straight through the diner’s entry hatch.

“Greetings, Percy,” said Roscoe, scanning the breakfast menu on a black slate just inside the entrance. “Looks like you have my favorite grubs today.”

“You’re getting the first,” said Percy. “A fresh box of them came in this morning.”

While Roscoe squeezed onto his favorite rock stool in the far corner, Percy put in his order and came over, wiping his greasy fins on his apron.

“I have been wondering for some time how you found this place?” Roscoe asked.

Percy loved to tell the story of the diner, so without hesitation he began:

“One winter, I was swimming along, avoiding the ice on the top of the River. The water was lower than usual, so I was down pretty deep. Just off the Rockport boulder, I noticed something gleaming down below. I dived down and saw the outline of the deck of a big ship. One of the portholes was ajar, so I wriggled inside. The dim passageway was coated with mud and slime, but as I inched forward, suddenly a door creaked open. To my surprise, I found myself in the galley – the old ship’s kitchen. I twirled around the counters, stove, and sink, and found that it was just the right size for me. I began to imagine myself as a chef, grabbing crawfish from the cabinets and tossing them onto the griddle. Grubs and worms for stirring into stew were at my fin tips in the lockers beneath the counter. I poked my head through some rusty doors on the main deck and found a big room that used to be the dining hall. I couldn’t shake the vision of myself as a diner’s short-order cook.”

Percy focused on Roscoe with one eye and flashed the other eye around to make sure that the diner was not filling up with customers. “By chance, at about that time,” he continued, “an eel friend introduced me to Angy, Unagi, and their teenage son, Elver, an eel family who lived in the shallows over by Grenadier Island. They were looking for winter work. As you know, Roscoe, eels like to burrow in the sand and mud, so I showed them the sunken ship and hired them to clean out the scum at the bottom of the hull. They scrubbed the cabinets spotless and polished the hardware until it shone like new.

“Eels work hard. They finished the job in no time. I was hooked, so to speak. I decided to open the diner for business in the spring, and I asked the eel family to stay on. Angy and Unagi’s job was to gather bottom-lying insect larvae that they foraged near their home to fill the pantries every day. During meal times, Elver worked as a busboy. He figured out how to use his long, flat body as a slide to shuffle plates, cups, and spoons from the dining room on the main deck to the galley below for wash up.

“Oh, here’s your order of grubs,” Percy took the bowl from the little perch waitress and slid it over to Roscoe. As he munched on his breakfast, Roscoe encouraged Percy to continue. “In the late evening, I wanted the diner to still be open, so I created a bar/tavern, the Minnow Bar, where fish could come for snacks and special drinks."

"The grand opening of the Frost Diner was scheduled on the first warm spring day so that fish migrating back into the river from down south would have a place to eat. When the water is cold and white with frost, it’s hard for most fish to find food in their home foraging grounds. I wanted them to feel welcome at the diner and to know that they would be well fed.”

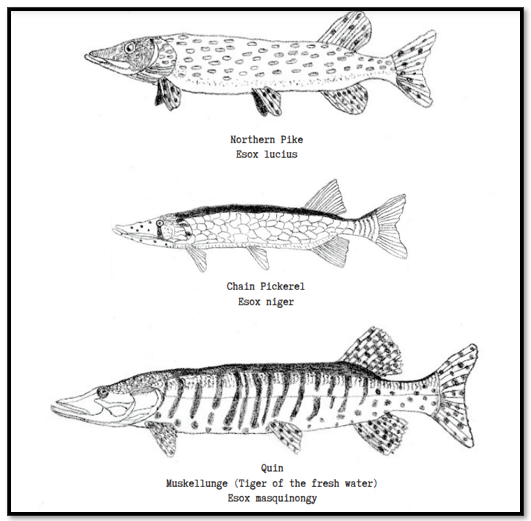

All of a sudden, Percy’s eye grew wide and his voice trailed off. He was staring at the entry hatch. A gang of Great Northern Pike had barged into the diner and draped themselves on the rock stools. With a quick wave of his fin to Roscoe, Percy darted back down to the galley and began to bang cabinet doors and scoop up slime balls, tossing them onto the griddle with a whack of his tail.

Roscoe had learned in Fish School that pike are always hungry and that they have been known to eat other fish, even their own kind. So, he gulped down his grubs, slid quietly off his rock stool and hid behind a seaweed curtain. When the ravenous pike were slurping slime balls and chomping on caterpillar legs, he slipped out the exit porthole and headed for home.

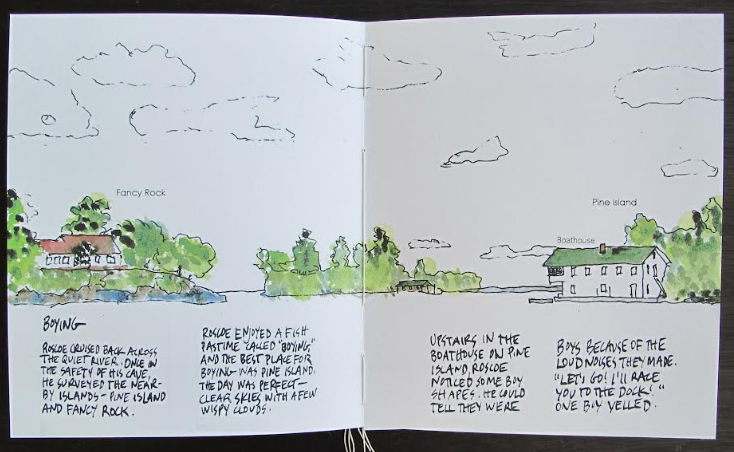

"Boying"

Roscoe cruised back across the quiet River. Once in the safety of his cave, with a full stomach, he wondered what games the day would bring. Through the transparent water he looked up at the clear blue sky with just a few wispy clouds. He knew a day like this would be perfect for games with children.

Roscoe’s underwater cave was nestled beneath two small islands – Pine Island and Fancy Rock – both of which were actually immense rocks that jutted out of the River, on which humans built their own sort of above-water caves that they called “boathouses.” On one end of Pine Island just such a large white structure hovered above the water, with two narrow channels at the bottom. In these channels, big floating shapes bobbed up and down and creaked against their ropes. In the summers this “boathouse” was filled with the family activities – noises that Roscoe could hear from inside his cave. Roscoe had internal ears, invisible from the outside, through which he could pick up sounds.

When the boy in the family made noises like, “Let’s go! Bring the fishing rods!” Roscoe knew that he would be down by the water soon.

On this morning, Roscoe heard many loud boy noises, so he knew that the children were already up and eating their own breakfast. He lost no time in darting over to the “boathouse” to be there before the boys came down to “go fishing.” He hid under the big vessels and extended his fins to swell-ride the warm currents while he waited. Roscoe was ready to “go boying.” And Roscoe knew that the best place for boying was Pine Island.

Pine Island was a summer paradise for boys. And Christopher Keats, the 11 year-old son, was no exception. As often as his parents allowed, he invited two friends, his cousin, and another Canadian boy from the mainland, to come for over-nights. They all slept in the bunkhouse, played ping-pong, and swam off the dock.

However, their favorite activity was fishing. Every morning, they gulped down their breakfast on the upstairs porch, and every morning, Christopher’s mother would say, “Watch the wind, and stay close to the dock. Make sure you have a life preserver handy. Now, go catch a big one for supper.”

The boys grabbed snorkels and flippers, long-handled nets, rods, and tins for worms. They tied towels around their waists over their bathing suits and headed down the narrow hallway for the outdoor stairs.

Roscoe recognized each boy’s footsteps from the underwater shockwaves. Christopher was first. The steps gently squeaked under his bare feet. The next boy’s foot stomped loudly, as the rubber soles of his sneakers struck the wooden step. The last, and smallest, boy’s feet were coated in something rubbery that slid and flopped, as though he had fins attached to his legs.

As the sun rose higher in the sky – when most fish retreat to deeper water – Roscoe watched the boys from his shady spot under the slats of the dock. The boys dumped their gear and spread out their towels on the weathered dock chairs.

“Let’s go swimming first,” one boy said. “Maybe we can see what’s down there.”

Christopher ran and jumped in, doing a belly flop off the dock. “Eeeee,” he screamed as he hit the water. The other boys were right behind, kicking their feet and beating the water with their hands. Roscoe held still, even though the splashes ruffled his scales and the shrieks hurt his inner ear tube.

Coming to the surface, the boys climbed the ladder and flopped down on the swimming dock, breathing heavily. But very soon they leapt into the water again and raced each other across the narrow channel to neighboring Fancy Rock. But because nobody was home and it was a very calm morning, they turned around and paddled up to the summit at the head of Pine Island. Splashing back to the dock ladder, they threw themselves, teeth chattering, onto their towels in the sun.

“What are they doing,” Roscoe wondered out loud to no one in particular. By jumping and splashing, they surely weren’t hunting for food – the commotion and noise chased away all the minnows and surface insects. And, anyway, they kept their mouths closed under water. Maybe they were trying to churn up seaweed for their midday meal, but then, again, they never carried anything to the surface.

“They are just playing boy,” Roscoe concluded. Suddenly, he had a bold idea. He could join in the game. Roscoe knew that he was faster under water than the flailing boys. So, he watched for his chance, and when one of them landed in the water again and swam near his hiding place, he darted out and tickled the boy’s toes with his dorsal fin.

“Yikes! What was that?” the boy yelped, as Roscoe scurried back under the dock. Excited now, Roscoe dove down and tore up some strips of seaweed with his mouth. When the next boy came along, he brushed the slimy stems under his tummy. The boy’s ear-piercing screams sent thrilling shivers up Roscoe’s scales. At midday, the mother called the boys for lunch. “I’m going to catch whatever is down there,” declared Christopher, as they were finishing their peanut-butter sandwiches and lemonade.

“No, I will catch it,” said his sister Margaret, who was ready to join the boys at the dock with her rod in hand, wearing her worm can between the pads of her life preserver. To Christopher’s surprise, she took off down the hallway for the boathouse stairs.

Roscoe had begun to doze off in the noontime heat when he was jolted awake by a splash. A juicy worm wiggled its way down to his level just beyond the slats of the dock. It dangled there, not sinking or moving with the current. Something about the worm’s stillness reminded Roscoe of the dangerous mayflies that had been the cause of the disappearance of family members in his youth.

Although the tempting worm would be an easy meal, Roscoe wanted to test it first. He circled it slowly. When it didn’t move on the second pass, he whacked it with his tail. Scurrying back to his hiding place under the dock, he watched as the worm wobbled and then sank a bit lower in the water. On the next pass, he got close enough to brush it with the side of his body. The worm shook uncontrollably and disappeared. Peering up through the ripples, Roscoe made out a red-and-white bobber attached to a string attached to a long pole attached to the girl’s hand. She brought the worm up close to her nose and, looking disappointed, pushed it further along the curved metal wire that Roscoe could see came to a sharp point.

“Here, let me try,” Christopher whispered. Margaret passed him the rod.

The worm plopped back down. Roscoe waited for a count of 10, and then bumped it again to let the boy know that he was in the game.

“You take it,” Christopher said to Margaret. “Whatever is down there is just not biting.”

Just then, Roscoe saw a school of Northern pike cruising towards the boathouse, scavenging for nymphs in the shallows. Roscoe hid beneath the dock, watching as they came upon the juicy night crawler that was still dangling from Margaret’s line. One of the pike lost control, opened its wide mouth, showing ferocious teeth, and swallowed the worm whole.

“Yikes!” Margaret shrieked as the line went taut. All the boys came running. “Hold on! Reel in slowly!” one yelled. Christopher put his finger to his lips. “Shhh,” he whispered. “Keep the line tight. Here, hand me a net.” The smallest boy shoved a net into his hand, and Christopher lowered it into the water just as the pike’s head came into sight. With one swift motion, he scooped up the pike’s body and brought it onto the dock. Grabbing the head by the gills, and being careful to avoid its razor-sharp teeth, Christopher eased the hook out of its jaw.

“That’s the biggest one we’ve caught so far,” he said. Margaret beamed. “Let’s release it before it breathes too much air.”

Soon, to Roscoe’s surprise, the gasping pike came flopping back down, a little dazed but unharmed. He watched as it lumbered off to the head of the island to nurse its sore mouth.

Excited now, all of the boys threaded worms on their hooks and dropped their lines side-by-side along the dock. From his hiding place, Roscoe watched and wondered who would be so foolish as to fall for those silent, still worms, especially after such a commotion. But he didn’t have long to wait, as a group of sassy youngsters were following the older pike. The pack included pickerel and saugers, whom Roscoe knew as the “punks” of the pike world. The punks made a sport, as well as a fashion, of being hooked and released. They challenged each other to get “piercings.”

On purpose, they would bite on the sharp-pointed bent metal wires that were dragged under water near bottom or jigged just beneath the surface. They studied hooks to tell the ones with and the ones without barbs – those nasty prongs that make the sharp points cut backwards as well as forwards.

Roscoe was excited to see for himself what the punks would do with the boys’ dangling worms. The lead pickerel in this group wasted no time in figuring out that the boys were using barbless hooks. In fact, he had seen the older pike swimming away, the one who had zoomed up through the top of the water just minutes before. The lead pickerel knew what to do to impress the other youngsters in the group.

He moved in on one of the wiggly worms and chomped down hard. Then the pickerel waited an instant for the line above to become slack, just before the boy realized that something had struck his worm and began reeling in. Rather than pulling against the worm, the pickerel wriggled a little forward towards the hook. In that instant, the hook released, and the fish spit it out and was free, with a small hole left in the side of its mouth – a piercing. He turned triumphantly and motioned to his gang to move on. Some of these punks had been pierced in this way more than 50 times. They had as many holes in their mouths and lips as spots on their bodies.

The boys above sat quietly for hours, their feet hanging over the side of the dock. They never tired of waiting to replay another catch and release. They had forgotten about keeping any fish for supper. The game was between them and the fish.

As the afternoon wore on, Roscoe thought about the absurdity of this boying activity, but he began to dream about how some day he might catch and release a boy.

[All illustrations by Sarah Bodine; Photographs courtesy of the Bodine/Keats family albums ©2024.]

By Sarah Bodine

Sarah Bodine is a writer, editor, designer and book artist. She spent the summers of her childhood at her great-grandfather’s house, known as Cliff Cottage, on the Ontario side of the St Lawrence River near Rockport. The three Keats children were her cousins, and she often ran an outboard across the Canadian channel to spend the night on Pine Island. John Keats, fondly known as JK, made Roscoe Fish the main character in his bedtime stories, which were loved by all the children. To this day, the next island generation is forever looking for Roscoe under the boats in the slip.