Building an Ice Boat

by: Manley L. Rusho

Bob LaShomb started it all, at least most of the adventure that I will relate here. It began in early February, around 1953. Bob, at that time, was the mail carrier for the US Mail from Clayton to Grindstone Island – two miles across the St. Lawrence River. A daunting task that most people could not even do once a week, let alone daily. The mail was under contract, which meant that each day it must be delivered to the island. During the summer when the river was open, the day’s crossings were mostly pleasant ones. In the fall, however, there could be 60 to 70 mph winds, heavy ice flows by December, and the river was usually frozen by January 30, annually. After the river froze, the journey across was challenging. Thin ice meant walking the two miles; on thicker ice, a horse or car was the preferred mode of travel. As spring approached, warming temperatures caused the ice to melt, making it the most dangerous time of year, but still the crossing had to be done.

All that stood between Bob and a very pleasant job was the River – 24 hours a day and 5 days a week, both ways. Bob’s idea was to build, or in this case obtain a ready built boat, an air boat that could go over both ice and water. He approached my father, Leon Rusho, Sr., with the idea to build one.

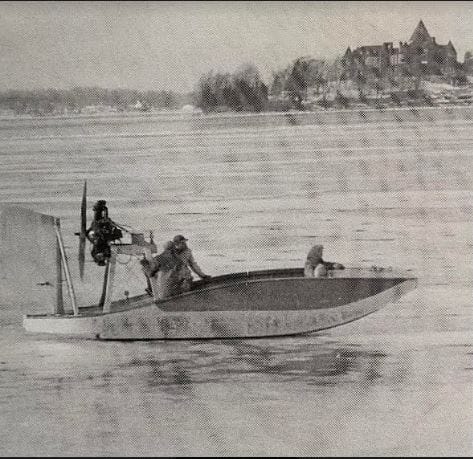

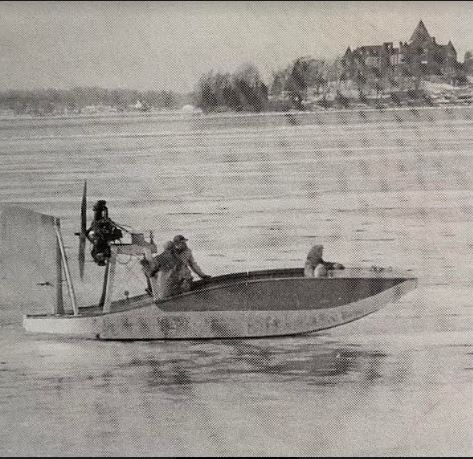

In Alexandria Bay, Bob had heard that there was a ready-made, substantial, air boat hull. A sturdily built craft that was about 4 feet high at the front deck and sloped towards the rear. The rear of the cockpit was about 2 feet high, the rear deck sloped to the stern, and there was no transom – only a pointed stern or duck tail.

Getting this monster over to Grindstone Island for my father to see, was a rather easy task as it was supported by two iron runners attached to the bottom and then could be towed across the ice. The hull was completely covered with high grade steel siding soldered together; a hull over a hull. It did, however, weigh only slightly less than the mechanized landing craft that my father owned, which was now moored silently along the main dock, waiting for spring.

For my father, this was a new challenge; aircraft engines were something to be played with and would provide him with a new quest for knowledge. The first engine we used was a 60 or 70 hp Franklin aircraft engine. All that we had was a propeller made for the airplane engine that we had, however, when the engine was mounted on our frame, the air boat would have run backwards because the prop was a "puller: and we needed a "pusher". My father got it running and in spite of the fact that the boat was sitting on solid concrete, when the little engine reached top rpms, the boat started toward the open door! The home-made engine bracket was sound, but we still needed a bigger engine.

Word spread that we needed a new engine. I managed to track down a WWII aircraft engine, stored in a barn east of the Thousand Islands Bridge in Ontario. I drove up, got it back to Grindstone, and at last, it was resting in my father’s shop. A real Phoenix – only a miracle could make it run. What I had delivered was a 5-cylinder Kinner motor, which at one time powered the WW II training planes that had filled the skies around the RCAF training base at Kingston. How the engine ended in the mud, in a shed, next to a barn, I'll never know. To my father, it was a gift from heaven; he hovered over that engine with love and wonder – it was the first radial he had ever seen and thus a brand new challenge. After many adjustments and bracing, the engine finally was installed on the air boat. A pusher prop was obtained somewhere, somehow and the process of learning how to start the engine began.

Since the engine had no starter, someone had to hold onto the engine with one hand and pull the prop through with the other. The carburetor was on the bottom of the engine, a massive thing maybe eight inches in diameter, all in the open and exposed to the elements. The throttle control was secured in the closed position by half of an everyday screen door spring, a short piece of wire was attached to the opposite side of the carburetor, and by pulling down on the wire you opened the throttle to control the speed of the engine. Pulling through the prop was a very hairy procedure, as the cylinders protruded past the engine. As someone pulled the prop through, there was a loud POW when one of the cylinders fired, then another, until all were firing and burning out the oil with a lot of smoke. If – and – when you got the engine started, the only steering control was a stick mounted on the right-hand side of the boat, with cables that vanished under the rear deck and reemerged through two pulleys, one on each side of the deck, and then attached to opposite sides of the large rudder, which was mounted on a rudder post. These were firmly moored to the bottom of the boat through the rear deck, with a semi-water proof fitting braced at the top with cables.

The monster settled down to operate with the smoothness of a 5-cylinder engine. To the rear of the boat, chunks of ice flew, as snow and other loose things inside the boathouse flew with abandon to the north side of the building. I was thrilled – not only did it run, it ran well! As my father increased the speed to almost wide open, the monster was now as tame as a pussy cat. Man, oh man, what a noise! The roar of the motor and the whine of the prop rebounded from the open boathouse doors – drowning out all other noises and conversations. We got the idea from my father that he wanted to move the boat, but full power on the motor did nothing. Someone came from the boathouse with a crow bar, a quick lift on the runners and we were away, moving slowly and leaving a trail of rust from each runner on the ice.

We rapidly moved to the outside of the bay; we were now about 100 yards from shore, with Bob steering, while my dad barehanded worked the throttle wire, face to the wind with a cigarette clamped between his lips. We turned to the west, slipped past the Red Horse Rock and headed for Boscobel Island and the open water. We slowed up and moved from the ice to the water; it was nicely done and she floated. We turned around, back onto the solid ice and headed for home. Bob and I played with this marvel like two kids with a new toy. Sunday was over and tomorrow we would attempt the first mail run with the ice punt.

Monday brought a usual March day; the ice was hardened from the freeze the night before, temps in the high teens or so, west wind maybe 10 to 12 mph. Down to the boathouse for my first look that day. The old punt was not a very attractive sight; from the side with its up-raised bow and flattened stern, it looked like a misshapen tadpole. The engine, covered by a castoff tarp, olive drab in color, added very little to the boat’s beauty. Her sides once gray, were marred by various dents and scrapes, with shades of red lead shown in some places. Nonetheless, in my view, the old punt was a thing of beauty, with the power that she possessed hidden by plain ugly. Bob arrived and to my surprise, so did Hildred Garnsey, to become the first passenger to ride to Clayton from Grindstone Island. Why she went I never asked and I never knew why anyone with good sense would ride with Bob and myself in that punt.

The Kinner engine purred like great cat; the 5 cylinders gave it a sound like no other, not smooth like even cylinder engines, just different. Hildred was aboard, a quick lift with the crow bar, I pulled open the throttle, Bob worked the rudder, and we sailed into history. A heavy flow of ice blocked the north channel, so we stayed on the solid flow. It was rough going, with frozen chunks of ice in nearly upright positions, bumping and grinding. Comforted by the steady roar of the engine, we pushed on with ease until we passed east of Calumet Island and into the open water of the Clayton channel, which was full of flowing ice in both large and small chunks. The river was opening into an ice-free world, which was to come in a day or two.

From the noise that we made, as we approached the Clayton dock, we had attracted maybe 30 people to watch our arrival. All of the boat slips below the sidewalk were full and at that time, next to what was the Golden Anchor restaurant, there was a long, fifty-foot boat slip, designed to load and unload passengers from the tour boats. The slip was still frozen solid and that was where Bob chose to land. He headed straight into the middle of the slip. I had slowed down because the punt, with little or no design to keep disrupted water away from the hull, had collected a covering of ice, not dangerous, simply making the trip uncomfortable. As we approached the slip, I became aware that a wall of ice had formed along the mouth of our intended sanctuary. When we had reached a point of no return, maybe 10 or 15 feet from the wall of ice, fearing that we would become stuck on the ice wall, I jerked down hard on the throttle. That motor, that wonderful old Phoenix, roared to life! We basically shot out of the water and over the ice wall at about 15 mph! Without any way to stop the machine, we slammed into the concrete wall at the end of the slip and stopped. Maybe shaken, most likely not, we climbed out of the punt. Hildred still had not spoken, and acted as if the trip were an everyday occurrence. Bob’s grandfather, who was a witness on the street, told Bob that he would give him all of the money that he had invested in the boat . . . if he would take it out and sink it. Bob never did.

By the next winter, at least a half dozen ice punts were on the river or under construction!

By Manley L. Rusho

Manley Rusho was born on Grindstone Island nine decades ago. This Editor and his many friends wish him continued good health and we thank him for sharing his memories with us. This is the second article for TI Life. See here for his first memory.