Bringing Muskellunge Back Through Science and Conservation

by: Bridgett McCann

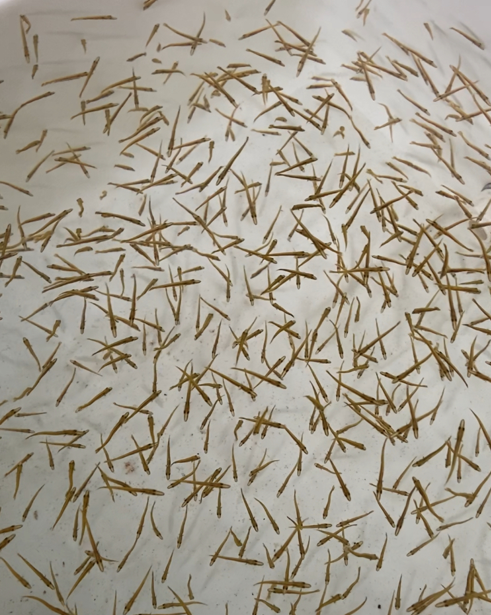

As morning mists lifts off Blind Bay, a canoe drifts quietly into the shallows. On board, Thousand Islands Biological Station (TIBS) lab manager Andrew Parnas, and Thousand Islands Land Trust (TILT) volunteer Owen Trela steady a cooler filled with thousands of young muskellunge— “muskies” to River locals. Today, these fragile fry will leave the safety of the lab and slip into the wild waters of the St. Lawrence, part of a decades-long effort to bring the River’s legendary predator back from the brink.

Before release, Andrew pauses. He dips a bucket into the bay and slowly mixes river water into the cooler. The process is patient, almost ceremonial. “We want to bring the water temperature closer to the River’s temperature,” he explains. “If you just dump them in, the shock makes them vulnerable to predators. This way, they have a better chance at survival.” Each bucket poured is a reminder of how science and land protection now work side by side, investing in the future of the River.

A Fish of Myth and Mystery

Few fish inspire reverence in the Thousand Islands quite like the muskellunge. Known as the “fish of ten thousand casts,” muskies embody patience, strength, and mystique. As apex predators, they once thrived in the Thousand Islands, but by the early 2000s, the story changed.

While they may be giants in lore and stature, they are also fragile. In the mid-2000s, the River’s muskie population was decimated. A mutating virus (Viral Hemorrhagic Septicemia, or VHS) swept through spawning grounds, killing off numerous mature adults. Invasive round gobies disrupted food webs and preyed on muskie eggs. The once-proud fishery that defined the Thousand Islands nearly collapsed.

“It was devastating,” recalls Dr. John Farrell, Director of TIBS. “Mass die-offs shook both the community and the science world. Muskies are more than just fish here—they’re part of the River’s identity.”

The Birth of a Biological Station

TIBS, perched on Governors Island near Clayton, NY, grew out of Dr. Farrell’s lifelong passion for aquatic science—and for the place most dear to his heart, the St. Lawrence River. With the long-term support of the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC), the US Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS), and the help of Muskies Inc., Muskies Canada International, and other major donors, Dr. Farrell established what would become a hub of international fisheries research.

“I’ve been honored to work with such incredible people on the River,” Dr. Farrell reflects. “Our students, partners, the community—they’re why TIBS exists.”

Each summer, the research station hums with activity as seasonal staff and interns set trap nets, monitor oxygen levels, tag fish with acoustic transmitters, and repair gear — all to better understand the River’s complex ecosystem and guide its recovery. Continued collaboration with the USFWS, which has supported spring netting and egg collection in Lake St. Lawrence near Massena, NY, for more than six years, has become an integral partnership — a reminder that every piece of this system is connected.

Science Meets Conservation

TIBS research has shown that fish rely on clean, complex, wetlands where young can feed, hide, and grow. This is where TILT’s mission—to conserve the lands and waters of the Thousand Islands—proves vital: healthy land creates a healthy River.

“For over 40 years, TILT has protected wetlands and nearshore habitats vital to wildlife and fisheries,” said Executive Director Jake Tibbles. “Flynn Bay—one of our first conserved sites—remains a premier muskie spawning ground, proving conservation’s lasting impact.” Other conserved sites, including Point Vivian, Crooked Creek, #9 Island, and Oak Island, also provide essential nursery habitat for muskies and other native fish.

Blind Bay offers another powerful example. Once identified as exceptionally productive, it became one of few long-term “indexing sites” on the River, tracking population trends over time. “Blind Bay became our barometer,” says Dr. Farrell. “It’s shown when the muskie population was stable, declining, or recovering.”

That barometer plummeted in the early 2000s when VHS and gobies ravaged fish communities. Then, in 2022, U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) proposed a facility at Blind Bay, which threatened to erase a vital spawning ground. TILT, backed with an outpouring of community supported, protected the site—keeping it a refuge for wildlife and research.

That same partnership has become a model for collaboration—showing how protecting land directly sustains life in the water. Although years of data from Blind Bay helped track declines and guides recovery, science alone isn’t enough. It takes sound management and public action. New York and Ontario raised size limits, and Save The River’s Muskie Release Program inspired anglers to embrace catch and release. Still, habitat is the key ingredient.

With Blind Bay offering refuge for young muskie and serving as a living laboratory, it’s protection feels all the more essential. In spring 2025, TIBS recorded a spawning pair, tagging both with acoustic transmitters to follow their movements. “That was a career-defining moment,” said Dr. Farrell. “Seeing a spawning pair shows recovery is possible.”

“Blind Bay’s story reminds us that science and conservation can’t work in isolation,” said Jake Tibbles. “By protecting critical habitats, TILT amplifies TIBS’s restoration work—giving the River’s top predator another chance at resilience.”

Stocking the Future

Each year, TIBS raises and releases thousands of young muskies into the River through its Muskie Recovery Program. The effort begins with an annual egg take—collecting, fertilizing, and incubating eggs from wild females before raising and releasing the fry back into the River.

The process is meticulous: fry begin on cultured Artemia—brine shrimp that mimic zooplankton but can’t survive in freshwater—then transition to live forage like fathead minnows. This is paired with an equally demanding monitoring schedule. Each spring, TIBS crews net spawning and nursery areas daily from May through June, returning in late summer and fall to seine wetlands (dragging a long net through shallow water to sample fish) and track young muskies—linking spawning success to juvenile survival.

“The River can still support muskies,” says Andrew Parnas. “We just have to get them through their most vulnerable stages in a complex, vegetated habitat.”

Adding a cutting-edge dimension to this work, graduate student Maggie Carroll, working in partnership with SUNY ESF and SUNY Oswego, is developing a genomics method to study muskie. Maggie explains, “This will let us measure stocking and natural reproduction success using small fin clips,” she explains. “Paired with acoustic telemetry, we can connect genetics and movement for a fuller picture of recovery.”

Stocking jump-starts recovery, while partners like TILT protect the wetlands and shorelines that make natural reproduction possible. “Stocking is just a bridge,” says Dr. Farrell. “Our goal is to restore natural reproduction.” Science helps young muskies survive; conservation ensures they still have a home when they enter the River.

Protecting Critical Bays

In addition to Blind Bay, TILT recently protected another keystone habitat: Windsong Bay, just upstream of the Iroquois Control Dam in the Town of Waddington. It’s TILT’s easternmost Preserve and one of the most productive muskellunge spawning areas in the Upper St. Lawrence.

When ownership shifted from the New York Power Authority to the Town of Waddington, talk of subdivision threatened its fragile wetlands. Recognizing the urgency, USFWS worked with the Fish Enhancement, Mitigation, and Research Fund (FEMRF), a fund established through the St. Lawrence Power Project relicensing and dedicated to re-enhancing fish populations. With FEMRF, NYPA’s, and the Waddington Town Board’s support, TILT acquired Windsong Bay in 2025, ensuring its permanent protection.

Windsong’s wetlands shelter muskies, eels, Blanding’s turtles, and grassland birds, filtering water and buffering floods. Each spring, muskies spawn in its shallow wetlands, and TIBS research shows adults born near Waddington can migrate extraordinary distances—sometimes as far upriver as Kingston, ON. “Without conservation, critical habitat will be lost,” says Dr. Farrell. “Sites like Windsong and Blind Bay give muskies the chance to reproduce naturally—and that’s the ultimate goal.”

And the benefits extend beyond the fish. The St. Lawrence fishery fuels the region’s economy, from national tournaments to local recreation. Protecting Windsong keeps that legacy—and the River’s resilience—alive, a testament to what swift, collaborative conservation can achieve.

The River as a Classroom

Beyond science and land protection, education ensures the River’s future. Conservation can protect a place on paper, but its survival depends on people who value it enough to keep it thriving. True success happens when the next generation understands what’s at stake—and feels personally connected to it. That’s why programs like TILT’s Ichthyologist for a Day and Save The River’s Floating Classroom matter so deeply—they connect kids directly to the River.

Students venture out on the water, peer through microscopes, feed baby muskies, and make discoveries that turn learning into wonder. “Kids are like sponges,” said Dr. Farrell. “When they hold a fish or help release one, you can see the light bulb go off. It’s not just an activity anymore—it becomes a memory. The River becomes something alive, exciting, and worth protecting. And those memories grow into lifelong care for the River.”

These hands-on experiences plant the first seeds of stewardship, inspiring some to return year after year and others toward future conservation work. All leave with a deeper respect for the St. Lawrence—its beauty, its life, and its role in the community. By creating these opportunities, TILT, STR, and TIBS ensure that the next generation can form lasting memories on the River, shaping future stewards who will carry this work forward.

Signs of Recovery

The River is starting to tell the story: the work of stocking, protecting, and educating is not just theoretical — it’s beginning to bear fruit. Acoustic tags placed on muskies in 2025, including the spawning pair mentioned earlier, are still pinging across the River, revealing adults returning to familiar waters year after year. There are still challenges: VHS, gobies, microplastics, but those steady signals, and the security of places like Flynn, Blind, and Windsong Bays, show resilience rising beneath the surface.

Just as important is the story of people. When the muskies were at their lowest, anglers chose conservation over competition. “The fish have a chance because the community wants them to,” said Dr. Farrell.

Science, protection, and community now move in rhythm—each release, each protected bay, each inspired student part of a quiet comeback, and a River learning to thrive again.

A Hopeful Future

The muskellunge’s story is one of resilience — of a River, a community, and a shared belief that restoration is possible. When the species neared collapse decades ago, it sparked a movement, embracing catch-and-release and proving that care, conservation, and research could recover a species.

The muskie is more than just a fish; it’s the pulse of the St. Lawrence — powerful, patient, and bound to the people who protect it. Its return is a testament to what’s possible when a community unites for something greater than itself — ensuring this River, and the life it sustains, endures for generations to come.

By Bridgett McCann, Thousand Islands Land Trust, Clayton, NY.

Bridgett McCann recently joined TILT as Communications Specialist. She is a graduate of St. Lawrence University with a Bachelor of Arts (B.A.) degree in Government and Environmental Studies, As a copy editor with experience communicating about conservation topics, she looks forward to making a positive impact in the Thousand Islands region, a place close to her heart. Originally from Rochester NY, Bridgett spent many summers in the Thousand Islands. Outside of professional pursuits, she enjoys spending quality time outdoors and on the River with her family, friends, and two rambunctious black labs River and Rosie.