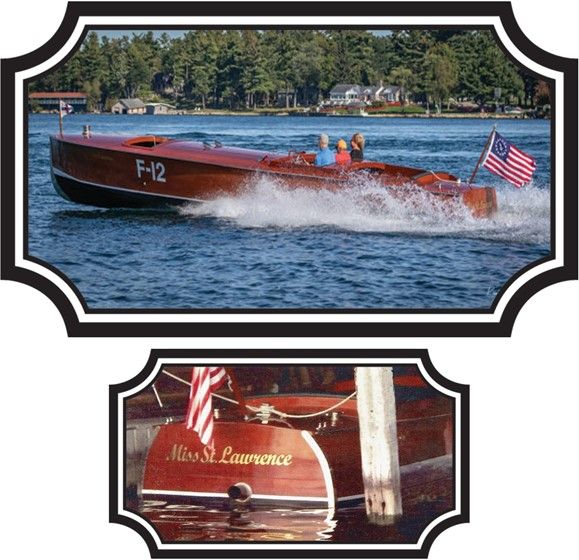

The Story of the Miss St. Lawrence

by: Tom Frauenheim

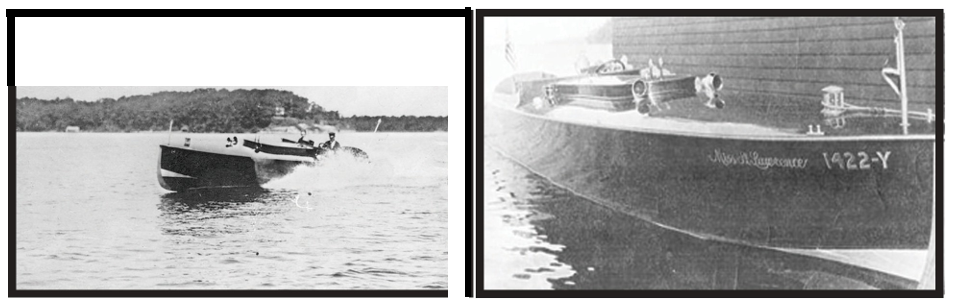

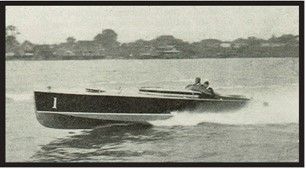

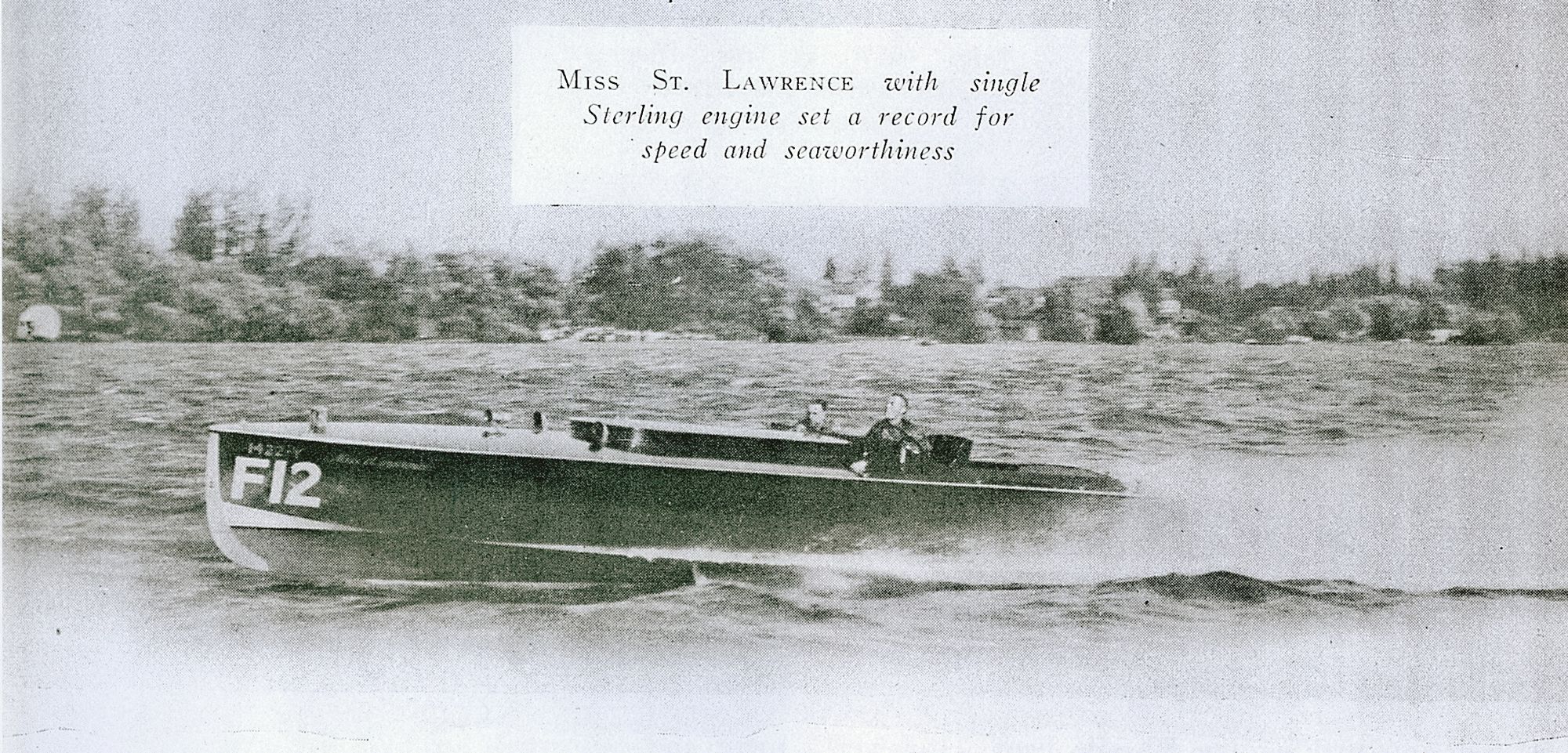

As the era of steamboats died out, a new breed of fast, sleek boats powered by gasoline engines rose to take their place. This was the age of handcrafted boats. Many individuals on the St. Lawrence dedicated themselves to designing, building, and racing these boats. Once upon a time, these sleek mahogany boats sliced through the blue of the St. Lawrence, their throaty engines roaring. That was one hundred years ago. Most of those boats are gone. Some are displayed in museums. Only a few still grace the Thousand Islands. This is the story of one such boat that still plies the waters that bears her name: Miss St. Lawrence.

Miss St. Lawrence

She was born in the cold and dreary winter of 1921/22 in Clayton, New York on the border of New York state and Canada. The summertime population of Thousand Island Park had all left in September and the lonely tasks related to the care and maintenance of the one hundred and twenty cottages was left to the few "year-rounders." The winters were long and cold and the only access to the mainland was by skiff or sled across the translucent St. Lawrence River.

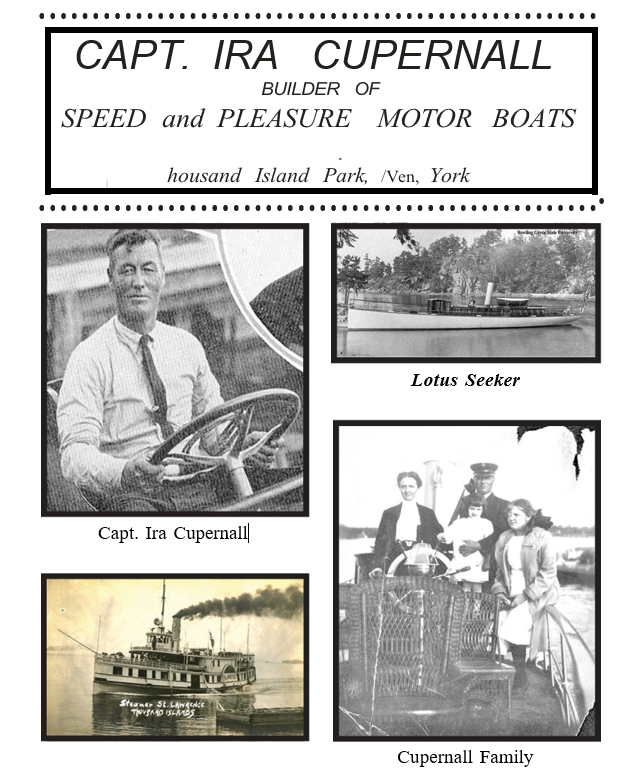

Ira Cupernall, builder of the Miss St. Lawrence, was one of ten children born into the Cupernall family at Fishers Landing in the Thousand Islands in 1870. He spent his entire life between Thousand Island Park, Fishers Landing and Clayton. He held a high degree in the R.A.M. Masons and was known by all as an honorable and dependable man with a strong character.

Ira started his career at sixteen as a deckhand on the ferry Islander. After being promoted to mate, he was moved through the wheelhouses of two other ferries owned by the Thousand Island Steamship Co., the Jessie Bain, and the St. Lawrence. He resigned this last post to be master of wealthy Edwin Holden's Lotus Seeker, the most gracious steam launch on the St. Lawrence in 1902. After the death of Edwin Holden in 1914, Ira turned to building boats and skiffs for the park residents. He is well known for two gasoline powered displacement launches Schoors Out I and Pan.

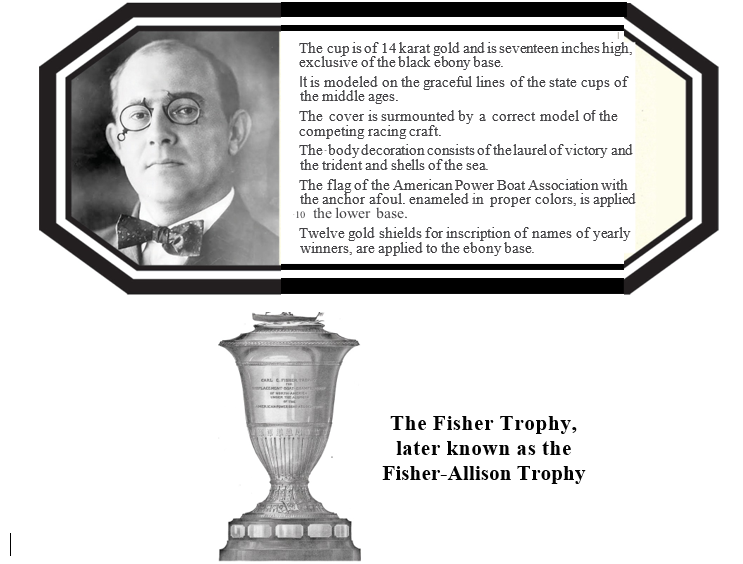

Introduction of the Gold Cup Regatta

The outstanding feature of the Gold Cup Regatta in 1920 was the 150 mile endurance race for a special class of runabout, powered by marine engines. The award was the Fisher Trophy, a $5,000 prize presented by Carl Fisher, founder of the Indianapolis Speedway, and a real estate developer in Miami, FL, and Montauk, NY.

Mr. Fisher felt that the previous wide-open rules of racing were doing very little to benefit the average boater or to allow fair competition. His idea of a race was between runabouts that were sturdy and practical rather than so lightly constructed as to barely last the race or be useless in rough water. Also, the surplus World War I airplane engines in general used at that time were seldom dependable enough to finish the race. Fisher wanted to see the development of dependable marine engines with a high horsepower to weight ratio.

The deed of gift required a minimum length of 32 feet, minimum speed of 35 mph and cubic inch in displacement of engine or engines not over 3000 cu in. The 150-mile endurance race was held in three 50-mile heats and no engine adjustments could be made between heats.

The races were held regardless of weather conditions. Engines had to be originally developed, built, and marketed as marine engines - aircraft engines were not allowed.

Dr. George H. Stephens, a Syracuse, N.Y physician, who summered on the St. Lawrence, decided to build a new boat that was 35 feet and would carry 11 people at 35 mph. After extensive research, Professor George F. Crouch, a most successful naval architect and teacher at the Webb Institute, told him it could not be done, because the marine motors of the 1920's did not have the horsepower to do the job. Crouch told Stephens to consider a fast runabout - "a refinement of the Rainbow"FS, which had won two legs of the 150 Mile Fisher Trophy Race. She would be thirty-five feet long by six feet seven inches wide with a hard chine "Hydroplane" hull. This was not a flat smooth hull as used by the hard riding racers of Chris Smith design, but rather a concave vee shape that runs the full length of the hull, allowing the whole boat to lift evenly rather than leap and crash from one wave to the next.

In late October 1921, Dr. Stephens ordered the plans for Crouch design #158 and Ira Cupernall started to build - the winters' work began. Captain Cupernall questioned Professor Crouch on how similar in design was this boat to the Rainbow and "would it be as fast?" Crouch answered, "if you build this boat lighter, it will be faster than Rainbow."

She was built at the docks of Murdock & Hutchinson in Clayton, New York for delivery in June of 1922 and had a few unusual construction details other than her underwater shape. The hull is oak ribbed with Mexican mahogany planking and copper rivet fasteners but nary a frame in sight.

Two rigid bulkheads fore and aft of the engine provide lateral stiffness while heavy full-length sheer strakes maintain longitudinal integrity in heavy seas. She was built slowly in a wilderness town by a man who well knew the water conditions she would have to endure. The power plant would be the tried-and-true Sterling Dolphin Special, built by the Sterling Engine Company of Buffalo, NY. This was a six-cylinder engine with a bore of 5 and ¾ inches and a stroke of 6 and ¾ inches producing 290 horsepower at 1950 rpm. The engine complete weighed 1965 lbs. and sold for a very competitive $4,500, no small change in this early era.

Rainbow was fast, but Professor Crouch told Stephens that the 35' boat would be faster if the weight was under the 6060 lbs. that Rainbow weighed. Keeping this in mind, Ira Cupernall eliminated the front cockpit saving 200 lbs. The sheer line was dropped 6" and every weight saving trick was incorporated. For strength, he built with rivets and not screws.

Dr. Stephens's letters kept saying "keep the weight down but don't sacrifice strength." The weight saving paid off when the speed of the Miss St. Lawrence well surpassed the other boats.

In the meantime, Gar Wood was building his 33' Baby Gar III powered with two 250 hp Fiat six-cylinder aviation motors, which were installed aft and run into Miss America's gear box to turn a single prop shaft. Wood had bought up WW I surplus aircraft motors and was converting them for marine use. The showdown between the marine and the aircraft powered boats was about to begin!

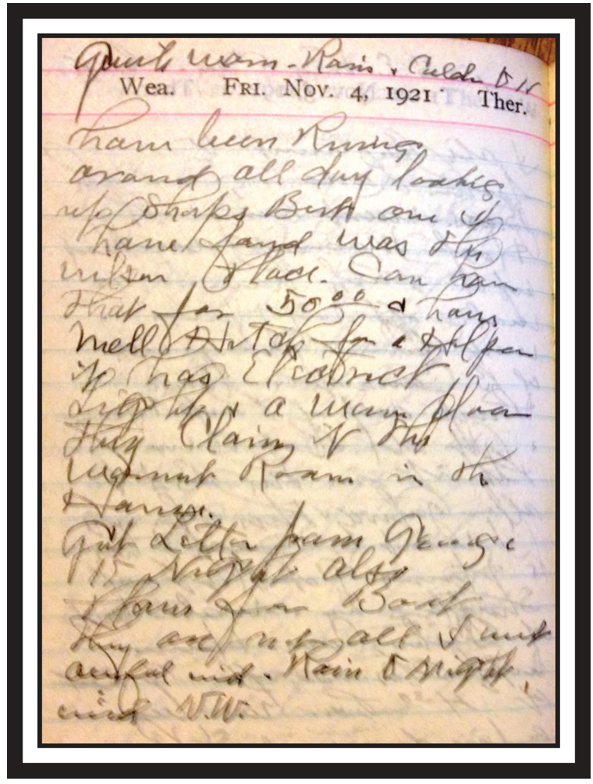

The Diary and Letters

The Miss St. Lawrence story has a lot more to it! The diaries and letters of Captain Cupernall and Dr. George Stephens had been saved in a trunk by the Cupernall family. Several generations held onto that trunk until Nan Dixon, wife of Bill Dixon, Ira's grandson, discovered, organized, and preserved the contents. Many questions on building the boat had no answers until this paperwork was discovered. Being a "year rounder" at the "Park" brought a close bond with family where everyone worked together to survive and prosper under hard living conditions.

George Stephens III had been told by Tommy Turgeon that the boat was built at the "Murdock and Hutchinson docks in Clayton" but "Buggy" Davis, Ira's grandson, said it was built in Ira's shop at the Park. Who was correct? The diary of Captain Cupernall held the answer but it was not until about 2010 when Nan Dixon shared it. Keeping a diary was a popular part of life in the early 1900's and an important part of a ship's captain's responsibility as well. Unfortunately, the Captain had writing that was extremely hard to read and only after years of concentration could it be deciphered.

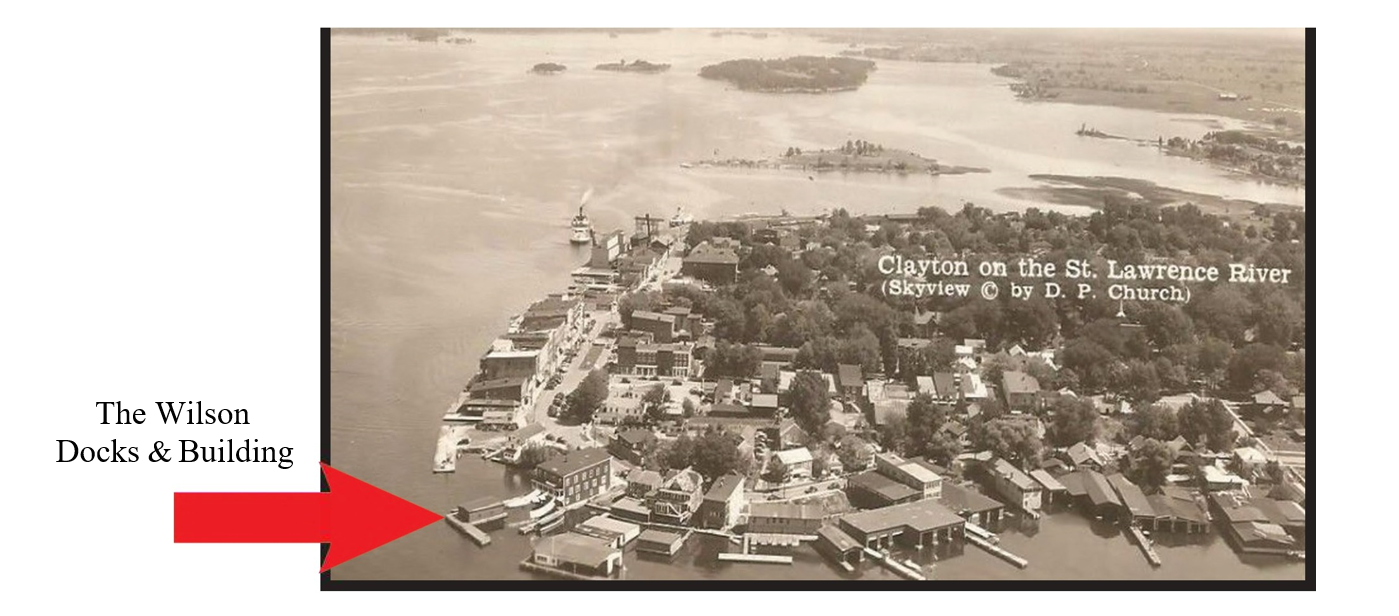

Nov 4, 1921.... The diary said "been running around all day looking into shops. Best one I have found was the Wilson place. Can have that for

$50."

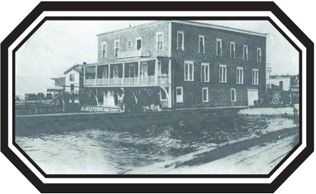

Finding a diary that mentioned the shop was one thing, finding where it had been located 90 years later was not as easy. No one knew what or where the "Wilson place "was. After months of searching, we got an "insurance map" of Clayton dated 1925. Bonnie Wilkinson had sent it over and lo and behold in hard to read print was "the Wilson place." Further searching led to Corbin's Shop in Clayton that specialized in historic St. Lawrence River life photography. Shane Hutchinson responded right away that this was his great uncle Melzer Hutchinson's place for many years. Melzer had bought the Little Spray and the Anywhere from Gord Wilson, both small deck tour boats, and probably the building too. The upper stories of the building were a rooming house and bottom floor, 40 feet by 72 feet was for storage, freight, or shop use. The other good news is that it had AC power and lights. Ira had no power tools of his own, but Dr. Stephens said he would buy an electric drill for building the boat.

The drawings for the boat arrived in Clayton on November 4, 1921. Ira showed the shop to George Stephens a few days later and work began on building the boat.

To start building, it was necessary to move Ira's boat shop in Thousand Island Park over to Clayton. Tools, supplies, steam boxes and a lot more. No small task as well as re-locating his family to Clayton for the winter months. In addition, the winter of 1921 / 22 was one of the coldest, with ice in the bays during late November and early December. By Christmas, the River was frozen with 24" of ice!

November 7, 1921 .... "Went to Otis Brooks Lumber Yard in Clayton and picked out the oak needed for the keel and chines." Next would be making the molds needed for framing the boat. More wood was needed for framing, keelsons, seats, and flooring. Dr. Stephens found 2 -12 inch by 12inch "tight knotted" Douglas fir timbers 32' feet long and had them shipped to Clayton for Ira to mill at Otis Brooks yard. Bert Conant was working with Ira - six days a week, 8 hours a day.

The diary states that the boat was built upright. After the transom, keel and chines were roughed out, the molds were made for each station on the plans. These were then set upright, and battens attached to keep everything fair and in place.

George Stephens III wrote in a letter "My dad was a friend of the president of the Butler Furniture Company in Syracuse. In 1921, the company sent a buyer to the mahogany forests in Honduras to search for the particular trees that the company wanted. The trees were marked as they stood and then felled and shipped via New York City to Syracuse. One of the trees selected by the buyer specifically for the Miss St. Lawrence and was marked for that purpose as it stood in the forest.

In those days, as now, there was a lot of thievery at every stage of transportation of any sort of goods including whole trees. So, the lumber buyer stayed right with the shipment of trees from when they were cut down in the forest and the huge trunks were loaded into the ships. He then sailed with the ship to New York and stayed with the shipment until it got to the sawmill to see that none of the wood was stolen."

The wood was shepherded all the way from the forest to the Butler Furniture and shipped by rail to Clayton. When the planking was unloaded in Clayton, it was put on a wagon and taken to the shop and manually loaded into the building. Heavy work and fighting the snow and cold all the way.

November 18, 1921 . . . The Cupernall family was staying with Aunt Jane Cook in Clayton for the winter. Someone in the family tested positive for Diphtheria so for the next ten days everyone was confined to the house. Cultures were taken several times before everyone tested negative. They have lost ten precious days of work.

December 4, 1921. . . Stephens writes " . . . have purchased a beautiful 18 inch Circassian walnut steering wheel."

December 9, 1921. . . Dr. Stephens writes "there are several different electric drills varying from $32.00 to $63.00 for the best one. I will take a chance and go with the best one."

December 12, 1921. . . "Went to the mill to get out battens and ribs. Will Hutchinson started today." Pay was $.50/hour and he stayed until May 18 when the boat was launched and taken to the Park. The work week was 6 days, 8 hours a day.

The remainder of December 1921 was spent cutting out floor frames, fairing up battens, steaming and installing ribs and making up and installing deck clamps. Dr. Stephens daily letters kept the Captain busy with new ideas and ways to make the boat the best. The plans showed double planking the hull sides but Ira changed to single plank, copper fastened to closely spaced strong oak ribs. The copper rivets were used because they held better than screws - took a lot more time to install but much more strength was added. The plans called for a 1 ½ inch prop shaft but this was reduced to 1 3/8 inch to save weight.

Sterling Engine recommended dropping the shaft angle to get the flow of water pushed straight back instead of down thus increasing speed. All these changes and ideas had to be decided on in early December to keep the building moving forward.

The mathematics and calculations that Ira had to make are an indication of his genius. George Crouch delivered a set of plans that showed a cockpit forward of the engine for the driver and a large seating cockpit aft. Ira and the Ditchburn Boat Company designed their own deck layout with a large steering cockpit aft of the motor. Ira eliminated the front cockpit to save weight. Ditchburn built five boats over a couple of years, and all had a cockpit forward.

January 1922. . . The plans called for sawn and bent frames on 6 inch centers. Every other bent frame had a sawn frame making this a very strong hull. The full-length oak ribs that ran from gunnel to gunnel were steamed and bent into the battened hull. "Finished planking port side and got a few boards on starboard side." Finished the sides started on "getting out the garboard planks."

January 14, 1922. . . "Got boat all planked except two pieces on starboard side. Got rivets and started on side planks." The planks were drilled, counter bored, rivets installed and then plugged.

February 4, 1922. . . "Bill Hutchinson will start tomorrow". Bert Conant, who had been with Ira since he started building the boat, quit in February.

There were now Bill and Will Hutchinson and George Flynn working on the boat with Ira. Work progressed through January and February. The bottom planking was doubled with a layer of airplane silk that was glued between the two layers of planking and then riveted together. Once the bottom was finished, the molds could be removed, and the keelsons and engine beds made up and installed. By February, the mahogany gunnels had been made up, steamed, and installed. The deck beams would soon be installed. The hull side planking was riveted to the oak steam bent frames and plugged.

March 1922. . . With the hull sides and bottom planked, the molds removed, and keelsons and engine beds installed, deck beams and deck planking installed and plugged, a lot of interior work began.

March 4, 1922. . . "hull marked off for waterline. Hull rubbed and filled and bottom red lead put on." All the scraping, planing and sanding on the hull is done and first stain applied. 2500 plugs cut for deck .... Some too dark, cut another 1000."

March 27, 1922. . . "Working on deck hatches. Bought 4 lights for shop.

Filling and caulking bottom seams. Boat is beginning to look like something!"

April 6, 1922. . . "finished cockpit coaming and put in dash. Getting sides rubbed down and varnished. Finishing detail work on hatches and seats."

April 20, 1922. . . A.E. Keech paints numbers on boat and letters transom and sides. She will be named Miss St. Lawrence. More rubbing and sanding and then varnish. Ira was the one who named the boat showing his love of the St Lawrence River and following naming of other outstanding boats referred to as "Miss."

April 29, 1922 . . . Sterling Engine ships the Sterling Dolphin Special

275 hp motor to Clayton.

May 16, 1922 . . . Getting ready to launch. "got her down on her saddles. Ready to move."

May 17, 1922 . . . Launched today and "moved her over to Haas and Holloway to set the engine in." Put engine in the following day after making some adjustments to the engine beds. Took her to the Park.

May 21, 1922 . . . "Got most of the wiring installed. John Lindsay with us every day. Had several problems that delayed starting." Bending the exhaust pipe proved to be one of the biggest obstacles to overcome and ate up days trying to get resolved.

June 24, 1922. . . "ran her on the Round Island course 46.5 mph.

June 29, 1922. . . Letter from Sterling Engine advises to make sure leading edge on rudder and strut is sharpened to a point. More prop problems when testing 20 inch by 30 inch props. Can't get 2000 rpm. Tried several manufacturers props. Columbian people say return prop and they will re check. In the meantime, they will make a new 20" by 30".

"John Lindsay shifted engine battery to starboard side opposite driver to help better balance boat. New cables made up."

July 7, 1922. . . Sterling Engine sends Dr. Stephens a letter inviting him to bring his boat to the Fisher Trophy races in Hamilton on August 24, 25, 26.

The Race

The 150 Mile Fisher- Allison Trophy Race of 1922 was held on August 24-26 at Hamilton, Ontario, Canada. Lake Ontario, the easternmost of the Great Lakes, is known for deep cold waters that carry long swells days after the winds have subsided. The racecourse was laid out in a two-mile lap with a turn at each end. The single pole proved a problem for many of the boats but not the Miss St. Lawrence, she could turn on a dime! The viewing was excellent, and the Hamilton Yacht Club did an outstanding job hosting the event. The starts were "standing starts" and Capt. Cupernall got a late start on Thursday but was third to start on Friday.

Thursday. . . The race on Thursday was run in ideal speedboat conditions. Gar Wood finished first with his twin engine, 500 hp, Baby Gar III. Colonel Jesse G. Vincent finished second in his 450 hp Packard powered Packard Baby Gar, third place went to Harry Greening's Rainbow II powered by two Sterling engines aggregating 500 hp. Miss St. Lawrence finishes fourth out of a seven boat field two seconds behind Rainbow II.

Friday. . . It was a particularly good race on Friday, for the second 50-mile heat, when the wind blew half a gale and a big white capped sea swept over the course. Ira Cupernall drove the Miss St. Lawrence in very rough conditions, leading to the last lap when he was narrowly passed by Gar Wood in Baby Gar Ill. Rainbow II went to the bottom in the rough seas when the pounding drove the engines through the hull.

Saturday. . . The third and final 50-mile leg was on Saturday and Captain Cupernall pushed Miss St. Lawrence to the limit leading all but Gar Wood in his twin engine, 500 hp boat. Lady luck dropped the ball on Miss St. Lawrence with only three laps to go in the final leg of the race - a connecting rod let go in the Sterling engine ending a great race for "marine" powered boat.

Part II will be published in July 2024.

By Tom Frauenheim

Tom Frauenheim is lifetime River Rat. When not on the River he lives in Tonawanda, NY. His research into the Miss St. Lawrence will be appreciated.

Header photo by Kent O. Smith. Jr. 2019. All photos courtesy of the author.

Comments

K Stephens Posewitz writes: Tom, Thank you so very much for taking the time to so thoroughly research this article. You've sussed out information that I never would have dreamed of! I'm particularly interested in the correspondence between my grandfather and Ira Cupernall. Dad (George III) would have loved this article. You do the Miss St Lawrence justice! BTW, is she still at the River? I truly miss it.