Team Rubicon Goes to Jamaica

by: Michael Laprade

The Epistle, December 2025

Editor’s Note: In April 2022, we published “So what did you do for Christmas?” I prefaced the article with an introduction, and I am repeating it here:

"Answer: Most of us visited with family and friends, even behind a mask. For one Islander though, Christmas 2021 was spent in a very different way."

Michael Leprade and his wife Janice, when not living on their beautiful little Honey Bee Island in the International Rift, are skipping back and forth between California and France. Each month, I look forward to seeing what trouble these two are getting into – or coming from . . ."

Skip ahead to September 2023, and news of another Florida hurricane, named Idalia, and I wondered, just wondered . . . and sure enough . . . So, we printed Michael’s 2023 story, "Not Forgotten", Taylor County Florida.

Now it’s February 2026 and when I spoke to Michael, I discovered and his Rubicon Team were called to Jamaica in the late fall – Michael’s and his teammates’ selfless work must be commended, and as a fellow islander and someone I call an amazing River Rat, I am extremely proud to have permission to publish his update from November 2025.

November 2025 and Team Rubicon goes to Jamaica

Last month (October 2025), I wrote that I was deployed to Alaska, but because of the government shutdown and airline flight cancellations, they could not book my flight from our small regional airport. Janice flew to Florida for a week to visit friends while I was to be away. Alas, the best laid plans of mice and men . . . 12 hours after she returned home, she was taking me back to the airport for my flight to Jamaica, where I had just been deployed with Team Rubicon.

Jamaica, you will recall, recently suffered a category 5 hurricane with 185 MPH sustained winds (300 kph) and some 250 MPH gusts (400 kph). Being on a National Disaster Response Team can be exciting in a twisted “Pee-wee's big adventure” sort of way.

It took two days to get there, with an overnight in Dallas, TX, at what the cool kids call the NOC (National Operation Center) for TR (Team Rubicon), where we packed much of our equipment and supplies, roofing tarps, chain saws, power and hand tools to fly out with us. We even flew our own ladders and roofing nails as supplies in Jamaica are so limited. The NOC is a large warehouse housing the command communication center to keep in touch with all the OP's (operations) going on all over the place. It also houses a ton of supplies and equipment to dispatch to resupply ongoing OP's.

While we usually respond stateside, this is my second two-week international deployment (Bahamas, 2019 was the first). As usual, we were warned that . . . "This is not a typical operation. It will take place in a remote, unforgiving environment with austere conditions. You will work in harsh, non-traditional settings with limited infrastructure, exposure to the elements, and physically demanding tasks."

Austere conditions? What should we expect?! We are in a disaster zone where everything has been smashed, crushed, levelled, and destroyed. NOTHING works. Isn't that why we’re here to help? Hurricane Melissa, a category 5 storm, hit Jamaica on October 28. The island, south of Cuba and off the coast of Haiti, is still reeling and will be recovering for years to come. The hurricane took out the electric grid, destroyed the water systems, and devastated the food supply. I have responded to many hurricanes but the damage on this one is unimaginable. The hurricane did not affect just a region, rather the entire country. I could have taken hundreds of pictures, but only a few are attached. The people aren't doing great either.

We landed in Montego Bay and drove to Whitehouse, ground zero, where the eye of the hurricane hit. A distance of 37 miles, which normally is an hour drive, took us 3 1/2 hours. This is what we classify as people in the "High social vulnerability index." Read "dirt poor." The hurricane may have done a number on them, but life here reminds me of a cross between Mexico and Morocco with rutted, impassible roads, with potholes every 100 feet that are big enough to swallow your car. Once away from the city, you are quickly in a 3rd world country.

Shopping in the few larger towns is like Soviet shopping. Little choice is available and when your purchases have been rung up you are directed to the customer service desk to get in line to use the only credit card machine available in the whole store. Meanwhile, other customers must wait with their purchases until you return to collect your items and receipts. Why don't you pay with cash, you ask? The Jamaican dollar is exchanged at $150 to $1 US. You would need a wheelbarrow to carry enough money for a serious order. I filled a tank of gas, and it cost over $100,000 (Jamaican $, or about $70 US) As you leave, your purchases face serious and comprehensive scrutiny by the security officer at the door.

Small hamlets along the way allow us to see how folks live and how little is available. There are no shopping centers or large stores of any kind. To say that they live in a food dessert would be an understatement. Few cars allow them to go anywhere.

L This is a restaurant. R: One for the road at the Bar? Maybe they have dancing?

Most homes are small, poorly built with unfinished cinder block, yards full of debris. And that was before the storm. Finding specific locations is hampered by the fact that few homes have posted addresses. Power lines are strewn all over the place, so huge parts of the country have no power. When it gets dark, no lights, no TV, no AC, no refrigeration. If you don't have a generator (most don't) you are out of luck. I only saw marginal interest on the part of citizens to clean up much. Still, they are a very friendly lot.

There are few boat shipments from the US per week and with the local government mandating that 80% of it must be building supplies, roof tarps and the like, non-essential items are hard to come by.

Store shelves; M: The tree we cut blocking access to a school. R: Most roofs are of this corrugated metal. In two weeks, I don't recall seeing an intact one. The metal gets wrapped around trees and power poles like aluminum foil.

With no power available at the water treatment plant, we treated all our water ourselves, assuming that it was contaminated. Water is usually trucked in and is expensive. For the folks out of town, some would find a stream or a creek and bathe in it. Downstream, people would do their laundry and at the bottom, some would draw drinking water from it . . . Little surprise that CLEAN drinking water is hard to come by and is at a premium. Our meals were touch and go. Breakfast was a peanut butter sandwich or a cup of noodles, lunch an MRE (military Meal Ready to Eat) in a foil pouch. They can be heated on the hot engine block of your car. If we were lucky, "Mercy Chefs," a charity group, would bring us a hot meal for dinner. As the time went by, things got better day by day. Meanwhile, Mercy Chefs would deliver one hot meal a day out in the hills and remote areas.

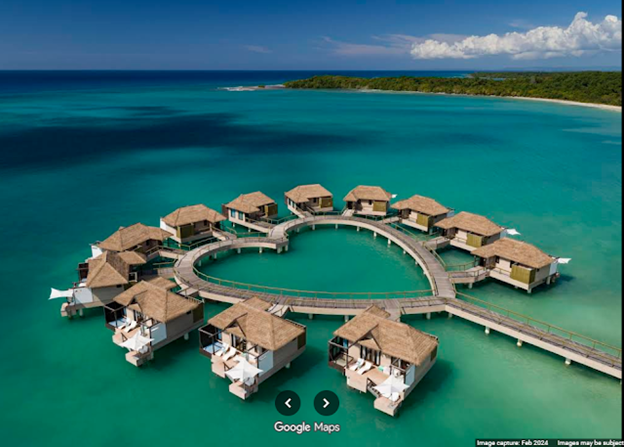

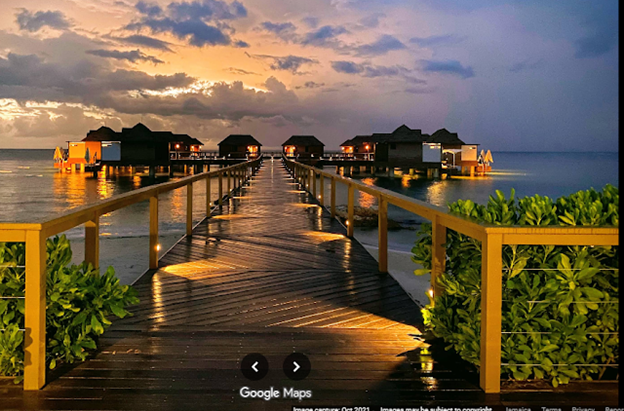

I hesitate to tell you about our accommodations lest you get the wrong idea and my wife never lets me deploy again! We are usually housed in a school gym, some warehouse, or a FEMA emergency trailer, on Red Cross cots. Here, we were in rooms at the Sandals Luxury Resort, often used by honeymooners or folks on romantic get-aways. People gladly pay $7000+ a week and some bungalows (below) are $3700 a night. It is all inclusive, with meals served by a butler, endless booze, and all amenities. You may have seen this ad for the place.

L: Nice, huh? My room was 100 yards from this. M: At night, it looks like this, says the ad. R: Reality

At the risk of bursting anyone's bubble, the reason why Sandals offered 14 rooms to TR volunteers is because the place now looks like this. Two of the rooms are to store our chainsaws, tarps, and assorted tools. The bad news is that we have a dearth of tools to work with, since we cannot be resupplied the way we are stateside. There is so little available here . . . and what is available is so expensive. We are in a 4-story building, but because the roofs are all damaged, rainwater flows through all four floors into most of our rooms.

When operational, Sandals is a high end, opulent, truly luxurious resort designed to cater to your every whim and wish. It is purposely designed to keep you IN by offering restaurants, bars, luxury shops, and a spectacular beach with all manner of water toys. It actively discourages you leaving (until your reservation is up) because it knows that the resort is a bubble of luxury in the middle of a sea of abject poverty. Outside the entry gate there is absolutely nothing. No restaurants. No shops. No activities. Nothing to visit or see. Why would you want to leave? A very short distance into the hills and it's all but caveman living. Yes, the hurricane made it worse, but there was little to destroy in the first place.

The Ad. . . The Current Look . . . The Ad. . . ; and Now.

They are closed for 6 months to make the considerable repairs. Most buildings need re-roofing (this is a big place, with 50 acres and two miles of beach), all pools and water features must be emptied, cleaned, and repaired, all outdoor furniture replaced and grounds re-landscaped. They have hundreds of large, gorgeous palm trees that are trashed and could take years to come back, so they must go. How they will replace them is beyond me, as every other tree I have seen anywhere is even worse.

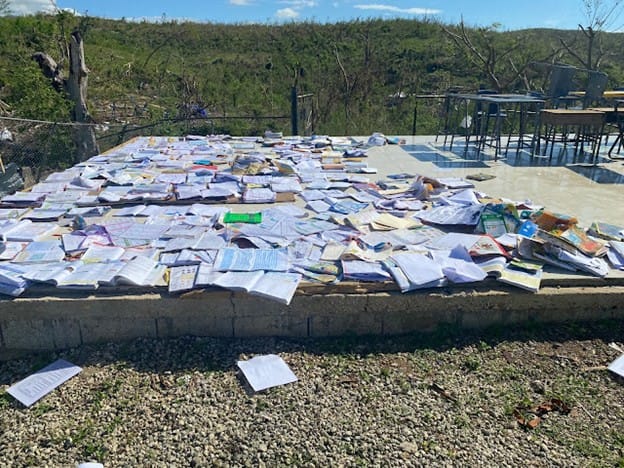

However, we are not here to help Sandals; they hired 600 of their own people. We are here to tarp roofs where sometimes there are only walls left. We cleaned up the debris at four schools (and tarped the roofs) and cut trees that blocked access, so that kids could return to their classes. When the kids return, they get fed, educated, get back into a social routine, and parents can return to work. The schools we opened allowed 500 families to send their kids back to school, well over 1,000 kids in all. The ministry of education told us there were 352 schools that needed to be tarped across the island.

A common sight: A classroom that needed a little love; Drying the kids’ soaked schoolbooks in the sun;

We cleared the debris around a hospital so it could reopen. They were doing procedures in a tent on their property. There are 13 clinics in the area but only three are functioning. We helped reopen the local police station and a community center. We focused on the community lifelines to help the most people possible in the time we were here. People were forever asking for help with their homes, for our tools, or tarps, or are just plain begging. We explain that we must concentrate on opening schools for their kids and clinics. Unfortunately, helping individual homeowners would keep us here for years. Good solid work for an extraordinary team of 24 trained people. I am so stinking proud to be with them, all “type A” personalities.

L: Entrance to a clinic we opened; R: Tarping the police station roof.

With the power out, there is no phone or internet service, so we brought a dozen Starlink mini satellite receivers with us. When we are down range out in the field, each team can keep in touch with our local headquarters, known as a Forward Operating Base. The cool kids call it the FOB. Two satellite phones serve in an emergency. We have a doctor, a nurse, a medic, and an EMT deployed with us. Since the medical system here is all but nonexistent, we also have two helicopters available for emergency evacuation. As hard as we tried, we could not get them to make a beer run for us.

L: They didn't make it. R: Every power pole everywhere looks just like this.

An often forgotten part of a disaster is the medical side of things. The medical team that deployed with us treated over 600 people in two weeks. The hospital has patients stacked three deep in the hallways. Our team hands out medications, with some patients saying they lost theirs in the hurricane. When asked what meds they needed, they often say things like "It was a yellow pill." All medical records were destroyed. I removed boxes of soaked files. Some patients need an MRI or CAT scan. The equipment was destroyed or they couldn't afford it. Prescriptions are written, but the pharmacy may not have the medication in stock or the people have no money to pay for it. Patients with insulin have no refrigeration (no power, remember) so they keep it in a thermos with ice. When the ice melts the insulin goes bad. It's a vicious cycle.

Sunday service is cancelled.

Our day starts at 5 AM and goes until 2 PM. The work is hard and the sun is really brutal, with temps reaching 93F (34C), and 92% humidity, so we call it a day. Besides, when we get back to base, there is still work to do, tasks like maintaining our chain saws to be ready for the next day. In some areas, there is a curfew at night, so we lay low. The buildings at this resort all suffered substantial roof damage (like everywhere), and when it rains, water goes through the rooms in all four floors. Insurance estimates of the damage to the resort are $250 million. This may be known as a luxury resort, but we are responsible for doing our own laundry in the bathtub in our room.

Ironically, disasters are often followed by a secondary, unspoken disaster. Donations. Random supplies flood in with no one to accept, sort, or distribute them, and with no place to store them. Such donations to disaster-struck communities from individuals and businesses are always given from the heart and with the best of intentions. Yet while good intentions may fuel the ‘everyman’ to donate physical goods during times of “great need,” increasingly, such donations create a second disaster. When people send unwanted, incorrect, or unusable goods to a disaster zone, they create a dumping zone. A secondary crisis that will have to be solved by unknown someone's, of unknown skill-sets, with little to no expertise, or the infrastructure to support, all while navigating the crisis at hand. This cruel cycle is repeated after every tragedy, every disaster, which pulls at nationwide heartstrings.

Broken refrigerators, dirty clothing, and weird things like fur coats or high heels are of little use in Jamaica. Those who want to ensure their hard-earned dollars deliver the exact items that are needed by disaster survivors, at the exact moment they are needed, and aren’t wasted, should donate cash, not things.

On my flight home, there was a fellow two seats in front of me coughing incessantly. I had a bad feeling about that. Sure enough, the next day at home, I came down with bronchitis. The real problem was that I inadvertently ‘shared’ and Janice came down with pneumonia. Not the best homecoming gift!

By Michael Laprade

It was back in 2009 when Kim Lunman Grout introduced readers of TI Life to Michael and his wife, Janice, in her article, “Honey Bee’s Magic.” They live on Honey Bee Island at the east end of the International Rift between Wellesley and Hill Islands. Michael is a former prison administrator and is also a Professional Magician. In October 2013, Michael and his wife Janice, started to write for TI Life. Since then you have learned about his many building projects and learned about his very special volunteer activities with Team Rubicon. (Articles) Now in 2026 he was called on again, and we as I have said before: "Please stay tuned, since this gentleman never seems to stop for a rest even if he says he is retired!" (THX Michael, you are amazing.)

All photos by the author