Schooner HMS "Speedy" Caught in a Storm

by: Richard Palmer

[Editor's note: This article by Richard Palmer is well beyond TI Life usual 1,200 word count. However, this piece of history deserves to be read in its entirety. Not only interesting, but a review of a navel disaster that sill remains a mystery.]

Few incidents had more of an impact on the early destinies of Upper Canada than the loss of the Provincial Marine Schooner HMS Speedy in Lake Ontario off Presqu’ile on October 8, 1804. The vessel was en route from York (Toronto) to Newcastle, the new district capital.

There were 20 or more persons aboard, including such important personages as the Honorable Thomas Cochran, the trial judge and Judge of the Court of King's Bench of Upper Canada; Sir Robert Isaac Dey Gray, the first Solicitor-General of Upper Canada; and Angus Mcdonell, defence lawyer and member of the Upper Canada House of Assembly. Other passengers included John Fiske, High Constable of York, and Jacob Herchmer, a prominent York merchant and member of a deeply-rooted United Empire Loyalist family.

In custody and shackled in the fore-peak of the 80-foot ship was a First Nations person named Ogetonicut. He was to be tried for murder in the Court of the Assizes (courts that administered civil and criminal law), having been charged with slaying John Sharpe, a trader, in the reedy reaches of Lake Scugog (a few miles north of Oshawa, ON). Ogetonicut had been turned over to the authorities by the chief of his Chippewa (Ojibwe) band for prosecution.

In Ogetonicut’s case, however, justice was not swift. It took the entire summer of 1804 to pinpoint exactly where on Lake Scugog the crime had occurred so that the trial could be held in the proper district. It was finally determined by a survey that Sharpe had been killed on Ball Point. Meanwhile, Ogetonicut languished in a jail in York. The authorities finally decided to try him in the new district of Newcastle, where a courthouse had been constructed.

This phantom metropolis was located 93 miles east of York. It had been surveyed and laid out by Alexander Aitken, Deputy Surveyor General, in November 1797, with the idea that the Home District, of which York was the capital, would be subdivided.

Newcastle, on paper, consisted of 76 one-acre plots and carried all the amenities of a well-planned community. It promised to outshine York in the near future. However, in reality, at the time it was not much more than a clearing, populated by twenty families. York’s population in 1801 had been 346. Kingston, which was closer, wasn’t much larger. Heading the list of early settlers at Newcastle were Captain Charles Selleck and his family. Another three families had settled on Presqu’ile Point.

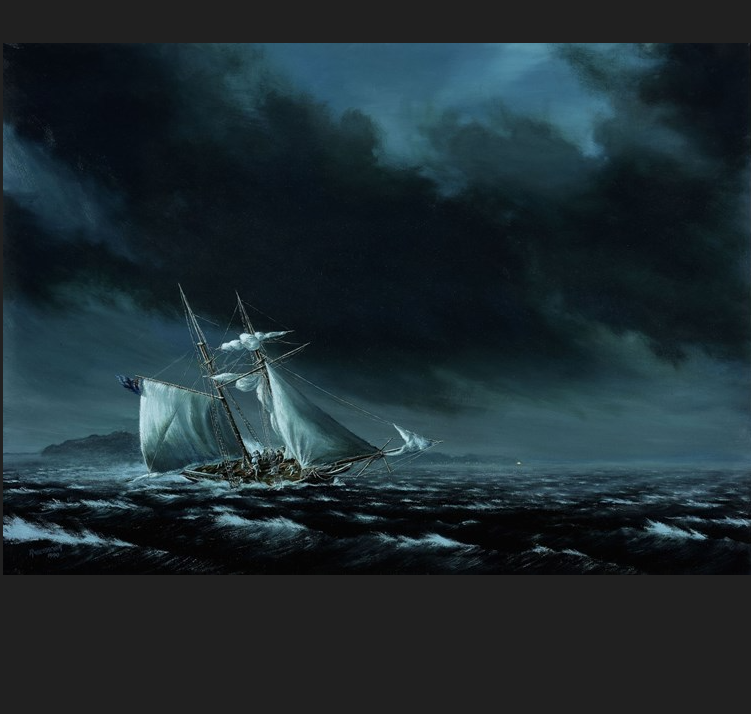

Schooner HMS Speedy caught in a storm on Lake Ontario. [Photo courtesy of the Great Lakes Historical Society.]

The Speedy, built in the Royal Navy Dockyard at Kingston in 1798, frequently made Newcastle a port of call. She carried passengers and freight between Newcastle and Niagara, which was one of the responsibilities of the Marine on the Lakes. The vessel soon showed signs of dry rot. Unseasoned, green timber, hard winters, hot summers, and poor ventilation made her unstable. Her captain, Lt. Thomas Paxton, would breathe a sigh of relief when she was finally anchored in a safe refuge.

The Speedy’s pumps were manned constantly, and Paxton experienced trouble keeping her afloat for about three seasons. He would look with envy at the new trading schooner Lady Murray that Capt. Selleck had built and fitted out. She lay snug in Presqu’ile Cove, loading pearl ash from the log piles the new settlers had burned. She was new, staunch, and tight as a drum. Capt. Selleck was prospering with his share of government contract work.

His Excellency, Peter Hunter, Major General, Commander in Chief and Lieutenant Governor, saw the trial of Ogetonicut as an excellent opportunity to inaugurate the new capital. On Sunday evening, October 7, 1804, the Town Crier of York exclaimed:

“All ashore that stay ashore!

All aboard that sail!”

At Governor Hunter’s command, HMS Speedy sailed immediately to inaugurate the new capital of the new District of Newcastle with a murder trial and possible hanging.

“All ashore that stay ashore!

All aboard that sail!”

On the quarterdeck stood Lt. Paxton, in his blues and whites, knee breeches, cocked hat, and gilt buttons. Some recalled him having a worried look. His naval career had not been a happy one, but then life in the Provincial Marine was generally hard.

Paxton had been appointed to second lieutenant in 1791, at three shillings and sixpence a day. It was six years before he was promoted to lieutenant and given command of this leaky transport. Two crewmen, Thomas Dobbs and William Young, deserted in the ship’s boat at Kingston, for which Paxton was censured. The abandoned boat was recovered, but the men were never caught.

Paxton was then ordered to take the Speedy out in a headwind, from the east to the west, with a cargo of First Nation goods. He soon returned because the Speedy’s main topmast had been carried away, and the ship leaking so badly that the cargo was damaged. He was again blamed for something over which he had no control. After repairs, Speedy was again packed off, this time with a cargo of pork. Speedy left York with its distinguished passengers under “a moderate breeze from the northwest.” Quietly, she glided down the lake while the members of Parliament and dignitaries dined, then slept in the quarterdeck cabins.

By morning, the vessel was floating calmly off Oshawa, 30 miles east of York. Canoes with trial witnesses put out, but the Speedy had so many passengers aboard, Paxton had to turn them away. William and Abram M. Farwell of Oshawa, fur-trading brothers who had employed Sharpe as storekeeper on Lake Scugog, agreed to paddle on with the witnesses and join the others when the schooner reached Presqu’ile. With the weather fair, the canoes made better time than the ship.

In the woods, Bitterskin, mother of Ogetonicut, was conjuring up bad medicine against the white men who had taken her son. She hated all men and was invoking the dark powers of the woods, it was said.

Her son, meanwhile, had managed to loosen a bolt in the wooden bulkhead (wall) of the fore-peak. Finding the wood soft, he scraped away, hoping to dig his way out. By nightfall and the schooner was in sight of Presqu’ile. In the hold, the penned-up fowls began to preen themselves and oil their feathers. The cocks crowed repeatedly.

The wind shifted, and snowflakes began to flutter down. Then the wind hit hard from the northeast, when the Speedy was within four miles of her destination. Paxton’s first thought was how he might avoid striking an unmarked underwater rock or reef known as the Devil’s Horse Block. There was no radar or chart to consult, and it was pitch black on the lake. The rock “stood like a hidden lion” in the Speedy’s path. It was a submarine crag 40 feet across, with eight fathoms of water right up to it, but only eight inches or so over it. Paxton knew the shore ranges and compass bearings perfectly. But how would you apply them in the dark?

“Fire the starboard gun!’’ he ordered.

After delays over wet powder, damp cartridges, and sodden linstock matches, a flintlock pistol flashed over the powder pan, ignited the charge, and the six-pounder roared. The passengers below thought the vessel was signaling her arrival and began donning their greatcoats in preparation for landing.

“A few moments yet, your Lordships, a few moments yet,” called down Lt. Paxton.

Answering the gun, Capt. Selleck and some of the others ashore had set fire to a large pile of brush, logs, and chips to guide the vessel in. Paxton breathed more freely. He could now get a fix on the Point, so he tacked the ill-named Speedy towards it in weary zig-zags. The clang of the overworked pumps added to the roar of wind in the sails, the noisy draining of water from the scuppers, and hiss of the seas.

No one heard Ogetonicut’s drowning gasps in the lake-filled fore-peak. His patient scraping away of the rotted wood, splinter by splinter, hour after hour, was first rewarded by wetness, then a sudden gush as the lake broke through the plank rib and deckhead. Shackled to the floor in his flooded prison, he drowned in the dark.

After much tacking, the Speedy was beyond the Horse Block. Paxton could tell by the compass bearing on the bonfire, now on his quarter, where he was.

“Stations forward!” he called to the crew. “Standby for stays! Helms a-lee!”

Speedy came into the wind and hung in irons, her snow-filled sails flailing wildly. She was so waterlogged that she would not steer. So, Paxton wore her around before the wind, hauled her up on the other tack as she gathered headway and bore away for the blaze of the beacon light. She could reach it in ten minutes. In the maneuvering, the Speedy had drifted to leeward, and she fell farther to leeward as she plunged suddenly through the snow with the muzzle of the lee gun level with the water.

Without warning, the Speedy smashed squarely on the hammerhead of the unseen Horse Block, and her masts went by the board. With a rumble felt more than heard, the reef split into fragments and collapsed, carrying down in its ruins the shattered vessel with all on board.

In an unsigned letter appearing in the Kingston Gazette on June 18, 1811, someone wrote: “The vessel was seen a few miles from her defined port on the evening of the 8th, when the wind began to blow strongly against her. The gale becoming violent, the vessel was seen bearing away. The whole night was dreadfully tempestuous, and the schooner is supposed to have foundered, as she was never heard of more. The binnacle, topmasts, and hen coops were picked up on the opposite side of the lake.”

Capt. Selleck and Paxton are said to have known about this “Devil’s Horse Block,” and once Selleck commented, “Whoever steps on this in the dark mounts for heaven or hell.” However, if it did exist, it disappeared with the wreck of the Speedy.

The wreck not only resulted in the deaths of several senior politicians and legal officers, but it also spelled the end of the District Town of Newcastle. All efforts to establish the capital here were soon abandoned. The one reality of the imagined city — the courthouse built for the murder trial — served as a tavern for a time. It stood for many years before being torn down to make way for a large cottage that later became a snack bar.

HMS Speedy was one of five gunships rushed into service, quickly built from green timber at Kingston in 1798, to help defend British Upper Canada from the perceived threat from the newly formed United States. That threat was later realized during the War of 1812, but Speedy would not survive to see service in that conflict. Speedy carried four-pound guns and had a 55-foot, two-masted hull, plus an over 20-foot (6 m) bowsprit, bringing her close to 80 feet in total length. Despite her name, Speedy was considered slow for her era. Because she was constructed from improperly seasoned green timber, she began to suffer leaks and dry rot almost immediately after her commissioning.

Ed Burtt, a wreck hunter, searched for the wreck, claimed to have found it in 1990, and hoped to salvage it under maritime law. He is said to have recovered some items from the wreck, potentially identifying it. He kept the location secret, planning to house relics in an exhibit space. He died in 2017 without revealing the location of the wreck.

Additional Resources

• Butts, Ed Shipwrecks, Monsters, and Mysteries of the Great Lakes. Toronto, Ontario, Canada: Tundra Books, 2010.

• Metcalfe, Willis, Canvas & Steam on Quinte Waters, South Bay, Ontario, 1979, pp. 124-126.

• Middleton, Jesse E. The Province of Ontario, Toronto, 1927. Vol. I, p. 136.

• Toronto Telegram, several articles, January-February, 1949.

by Richard Palmer

Richard Palmer is a retired newspaper editor and reporter, and he was well known for his weekly historical columns for the “Oswego Palladium-Times,” called "On the Waterfront." His first article for TI Life was written in January 2015, and since then, he has dozens of articles and more. He is a voracious researcher, and TI Life readers certainly benefit from his interests.

Editor's Note: 11 Articles published before June 2019, and 30 articles printed in the new format.