The Origins of Gananoque, Part I

by: Paul Coté

Several histories have been written about Gananoque in books and monographs. But most have been written from an academic point of view. I make no pretense of being an academic. The following is written from a personal perspective. In a short article such as this, not all aspects of its history can be covered. With that said, there are certain things at which I want to take a look.

The origins of the name of Gananoque is a minefield and not for the faint of heart. Several authors have taken a crack at unravelling this quagmire and have only produced maybes. The problem, of course, has to do with language. Researchers have looked at the Mohawk and Mississauga languages (they are the ones most closely associated with the Thousand Islands) and found that these tribes also had dialects that could skew pronunciations. On top of that, we must add the French and English mangling of what they thought they heard. Examples abound.

One would think that those closest to Gananoque’s founding would be the best source, but no, that isn’t the case. H W Hawke, in his 1970 The Story of Gananoque, presents some of the quandaries. After speculating on some native words and expressions he cites several European versions. The following paragraph from page 2 of his book shows why it is such a minefield.

“The Indian pronunciation of the name was very much like KAH-NON-NOH-KWEN. Count de Frontenac in 1673 spelled it Onnondakoui, and in a Crown Patent to Joel Stone of seven hundred acres, dated 1798, the land is described as ‘A certain triangular tract upon the River Cadanoryhqua’. In 1793 Stone dated his letters from Cadanoghqua, and a few years later wrote more simply Cadanocqui. In 1818 it became Ganenoquey, and shortly thereafter that the present form came into general use. On an early map (Morgan’s) the name of the St Lawrence River is Ga-na-wa-ge. The name is now pronounced with the accent on the third syllable: Ga-na-NOCK-wee.”

Frank Eames’ monograph Gananoque: its name and origin printed in 1942, adds even more complexity.

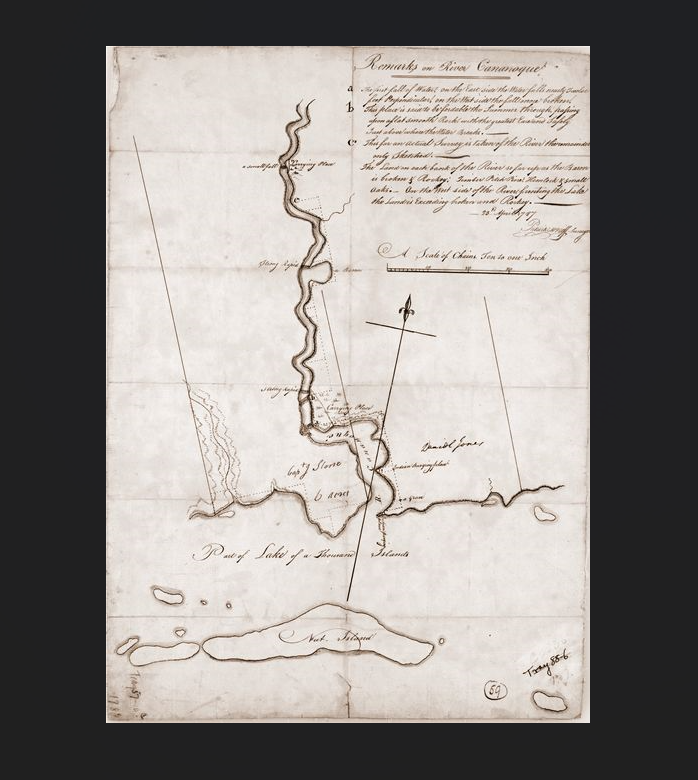

The Count de Frontenac’s words on his 1673 trip from Montreal to establish a fort at Cataraqui (Kingston) are worth repeating.

“On the 4th of July the route passed through the most delightful country in the world. The river was spangled with islands on which were only oaks and hardwoods; the banks of the mainland were equally handsome, the timber being very clean and lofty, forming a forest equal to the most beautiful in France…On the eleventh a good days journey was made, having passed all that vast group of islands with which the river is studded, and camped at a point above the river called by the Indians ‘Onnondakoui’, up which many go hunting. It has a very considerable channel.” [With that it is better to move to another topic.]

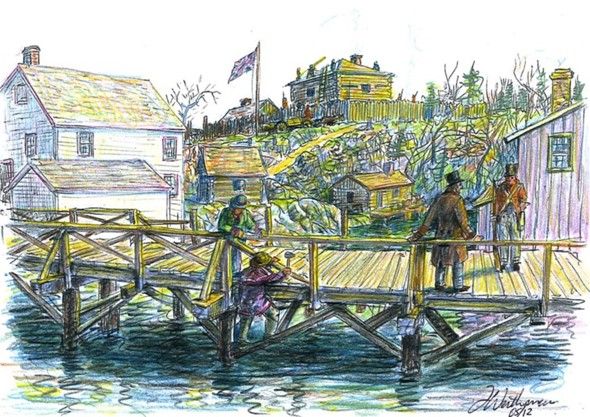

The story of Joel Stone being dropped off at his future home in 1792 is well known. A bateau on its way to Kingston set him and his baggage off near where Joel Stone Park and the waterfront museums are now located. This has been called Shipway Point and also Protestant Point. Not one tree had yet been cut to transform that wilderness into what would become Gananoque. As the story goes, he put up a white flag (some say handkerchief) to attract attention, presumably of any other settlers in the area. This did attract the notice of a Quebecois man named John Carey (probably Jean Carré) and some native companions on Cunningham Island (the island closest to the municipal marina). Stone and Carey went into a sort of partnership to sell provisions to passers-by and to provide lodging and drinks to any who wished, at Stone’s landing place. That didn’t work out too well. When the new Governor General of the Province, John Simcoe, stopped there in June 1792, he and his wife found the place so dirty that they slept in a tent instead. Stone and Carey’s shanty burned about a year later and their partnership dissolved. That was the end of Stone’s first house.

His next residence was a log house on what is now King St West where Tanner and Church Streets intersect. Behind this log cabin were the rapids where the upper dam would be built in 1826. The flat rocky bottom (still obvious) below the rapids was the only place where travelers could cross the river once the spring freshet had passed. That rocky crossing is still visible at the foot of the upper dam. This gave Stone and his mercantile businesses access to all who travelled by land. Across the street he granted land for a church and a school. A school was built by subscription in 1816 but a church wasn’t built until the 1830s, and that was on the east side of the River.

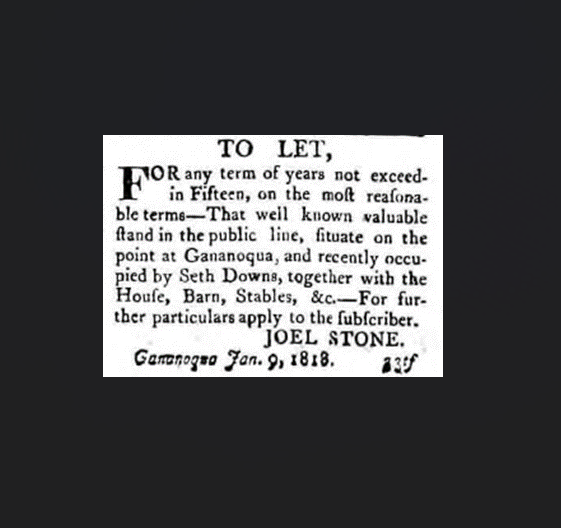

The ever enterprising Stone wasn’t satisfied with his log house and built his next residence back where his first shanty had been located. It was a frame building and was known as the Red House because he had it painted red. This house in turn became an inn, operated by Seth Downs during the War of 1812. Downs was also the man who built the first school in 1816. The 1813 township census also notes that Downs, John Lloyd Jr (from a well-known local farm family) and Silas Pearson (previously the ferryman before the first bridge was built) were on parole, indicating they had been among the prisoners taken by Forsyth in his 1812 sacking of Gananoque. It also listed 23 men who were in the militia at the time, variously noted as flank, infantry, and enlisted.

Stone’s next house was built where the old St Lawrence Steel and Wire plant was later erected. It was painted yellow and therefore called the Yellow House. Today, part of the old factory has been converted to medical facilities. Riverport Marina is immediately south of it. This was where Stone and his wife were living during the war and where his wife was wounded.

Not satisfied with that house, he next built the White House. It was located in what is now the parking lot for Riva restaurant. That Stone homestead can be seen in the 1839 Ainslie painting. [See Part II of this essay for this painting.] Sadly, although the town claims to pride itself on its history, none of these places have plaques highlighting their importance to the history of the town.

It was with Lieutenant Governor Simcoe’s visit in June of 1792 that we first hear about mills. Mrs Simcoe, in her diary of the excursion, wrote “Mr Stone is building a saw mill here opposite Mr Johnstone’s (sic). It will work 15 saws at once.” She also did a water colour but it only shows Johnson’s mill.

Besides Simcoe’s stopover in 1792, another distinguished visitor showed up at Stone’s mill in 1795. Francois Alexandre Frederic La Rochefoucault-Liancourt, Duke de Rochefoucault-Liancourt, was on a visit to Canada when his trip abruptly ended at the future Gananoque in July 1795. For political reasons, the Governor of Upper Canada had revoked his permission to be in the Province. He did take the opportunity to inspect Stone’s mill and made the following observations and gives Stone’s name for his mill:

“He is owner of a saw mill which is situated on the creek Guansignouque (sic), and has two movements [gang saw and circular saw – added by Eames], one of which works fourteen saws and the other only one. The former may be widened and narrowed, but frequently cannot work all at once, from the size of the logs and the thickness of the boards. We saw thirteen saws going; a log, fifteen feet in length was cut into boards in thirty seven minutes. The same power which moves the saws, lifts also, as it does near the falls of Niagara, the logs on the jack. For sawing of logs the Captain takes half the boards; the price of the latter is three shillings for one hundred feet, if one inch in thickness, four shillings and six pence if one inch and a half and five shillings if two…On the other side of the creek, facing Dutchmill – this is the name of Captain Stone’s mill – stands another mill, which belongs to Mr [Sir John] Johnson, who uses half the water of the creek.

We viewed the latter only at a distance from the shore, the whole prospect is wild, pleasing and romantic, and made me sincerely regret my unskillfulness in drawing.”

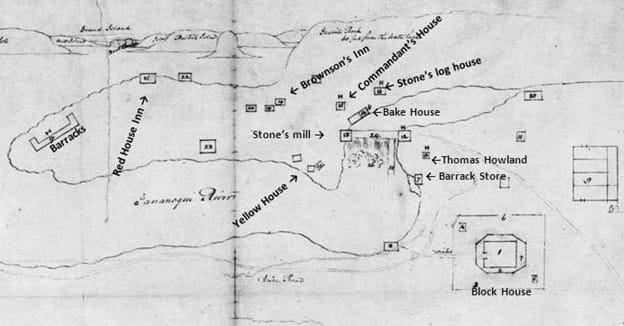

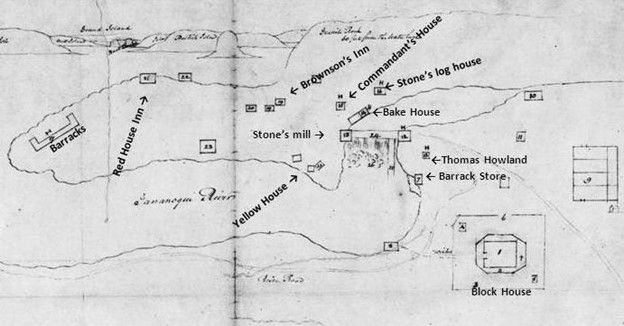

Frank Eames, in his comprehensive booklet Gananoque Blockhouse, 1813-1859, spent several pages (pages 5 – 7) elaborating on the 26 landmarks included in the map below. As enlightening as it was, in his own way Eames also raised some questions, mainly about which houses Joel Stone really had built. The location of the Red House is a settled fact, but when he broached the subject of the Yellow house (#23), he states it was “the Colonel Stone home at the time of Forsyth’s raid. Its site was below the lower dam, some two hundred yards, and on the west side of the River.” The present Medical Centre, beside Riverport Marina, now occupies that site. This raises the problem of the two #23s, which Eames doesn’t address. The second is the box slightly downriver from where he located the Yellow House (which is also marked #23).

I don’t think there is any question of the location of Stone’s log house as shown on the map, where King St W intersects Church and Tanner Streets. Eames contradicts himself about the location of the White House (Stone’s last residence). He states that the Bake House (#14) “stood on the water’s edge of the upper pond and in rear of the later dwelling Stone built, and which became his last dwelling place. The actual site is immediately opposite the Golden Apple Tavern [now Riva]. It was known as the White House . . . The old Bake House was taken down about 1904 or 1905; the writer was in this building many times while it was occupied as a dwelling.”

Number 16, ‘Commandant’s House under part of the Dragoon’s Quarters,’ confuses the issue as Eames states “This was on the site of the present Golden Apple Tavern (now Riva), and at that day it faced the ferry crossing and now Highway 2. Silas Person (sic) was the ferryman, although the Colonel held the charter. The Commandant was Colonel Stone, commissioned by Gov. Gore as Colonel of the Leeds Militia, January 3rd, 1809.” The question arises, did Stone ever live in that house?

One other landmark deserves attention as well. Number 17, marked as Barracks on the 1815 map, has a bit of a side story. The militia at Gananoque was ill prepared for the war. Although Stone was appointed as a Colonel in the 2nd Leeds Militia, he had little military training or experience. A little more than a month after the raid on Gananoque, Stone wrote to Colonel Lethbridge

“I have furnished barracks for one hundred and twenty men, and they are all on the spot, including the Rifle Company now on duty here. And all are in the greatest want of almost every necessary. And I have this day received a letter from Col Vincent referring me to you for stoves, blankets, etc. and I must observe that we are in as great want of shoes, pantaloons, jackets, and watch coats for the Guard.”

It was the following year before the Block House was finished.

In 1809 William Moore Stone,Stone’s son by his first wife, Leah Moore, who had been a promising young man and the future heir of his father, died at only 28 years of age. This was devastating to Stone, as his enterprise was now in doubt. But in 1811, a person by the name of Charles McDonald arrived at his settlement. It isn’t clear whether his arrival was by design or happenstance. McDonald was from a business background and ambitious. He formed a partnership with Stone, and the next year married Stone’s daughter Mary, thereby cementing a family relationship as well as a business one.

“For some time, Colonel Stone did not do much towards improving his property, but finally leased the water power to Charles McDonald, his son-in-law, who carried on an extensive business, active operation commencing about the year 1812. Charles McDonald built a saw mill and a small grist mill, and engaged in the lumber trade, shipping large quantities to Quebec, and also supplying the Government at Kingston for shipbuilding purposes, several war vessels being on the stocks at the time. In 1817, Charles McDonald was joined by his brother John, and about ten years after by another brother, Collin.”

Charles McDonald’s enterprising nature is seen in the Township assessments (1800-1850). By 1813, it was he who was taxed for Stone’s saw mill. By 1815, McDonald and Ephraim Webster were the first in the township to be levied for merchant shops. Curiously, the earlier assessors (from 1800) never levied Stone for one, even though he was noted as having a shop, or perhaps it was better called a trading post, in the late 1790s.

With the arrival of John McDonald in 1817, the brothers formed a partnership called C & J McDonald. The next few decades would be dominated by the McDonald’s control of the developing settlement of Gananoque.

Endnotes:

- Gananoque Blockhouse 1813-1859, Frank Eames, self-published, booklet, 1951, page 7, # 21. Eames also mentioned that in 1792, Stone supposedly built a schooner, the Leeds Trader, on that point. Later, the steamboat William IV was built there and even later, a Mr Moffat built a steam yacht Clara Louise, named after his two daughters.

- Alan Lindsay, TILife Magazine, 13 Feb 2013, "Pointe La Morte and Lindsay Point’s Place in Hist".

- Ruth McKenzie, Leeds and Grenville: their first two hundred years, 1867, United Counties of Leeds and Grenville, McClelland and Stewart, Toronto; page 27.

- Eames, page 12.

- This can’t be when Stone was commissioned as a Colonel, as the assessments give him that title in 1795 and 1804.

- Extract from a letter from Col Stone to Col Lethbridge dated 25 Oct 1812; Archives of Ontario, Reference code F 536, MU 2892

- Thaddeus Leavitt, History of Leeds and Grenville, Recorder Press, Brockville, 1879; reprinted by Mika Silk Screening Ltd, 1972, page 126.

- Archives of Ontario, Front of Leeds and Lansdowne , microfilm # MS 2552 https://www.archives.gov.on.ca/en/microfilm/municipal_records_microfilm_t.aspx#johnstown

By Paul Coté

Paul Coté is a resident of Gananoque. He has socialized and worked on the River for most of his life. History has always been a passion and he is a self-confessed genealogy addict. Recently retired from contracting on the river, he now has time to pursue and write about his research. His latest book, Sheatown: A Vanished Irish Catholic Community in Protestant Yonge Township, Leeds County was published and reviewed in TI Life December 2019 issue.