"Ocean Wave" Fire Took Twenty-Eight Lives

by: Richard Palmer

A nightmarish shipwreck on Lake Ontario occurred on the cold and windy night of April 29, 1853, when the freight and passenger steamer Ocean Wave burned and sank. She was two and a half miles off Point Traverse, about 40 miles west of Kingston, where she was headed.

Twenty-one passengers and 16 crewmen perished. The vessel was making its weekly round trip between Hamilton, ON, and Ogdensburg, NY, and was headed for Kingston. She was commanded by Captain Allison Wright. Although the contemporary accounts are somewhat confusing about the numbers, it appeared that there were 26 passengers, including four young children, and a crew of 32.

There was no Coast Guard in those times, so rescuers were other passing vessels or the farmers who lived along the coastline of the lake. One such person was David Dulmage of South Bay, who was awakened at 2 am by the reflection of bright flames through his bedroom window. This and the topping of a steam whistle told him that something was wrong. He ran outside and rang his dinner bell to alert his neighbors, then they rushed down a frozen, muddy road to Point Traverse, two miles away. There they pushed off in a fishing boat and quickly rowed out to the steamer, which by now was a floating inferno. Amid the flames, screaming passengers were jumping into the frigid waters of the lake. So hot were the flames that the sails of two schooners, the Georgiana of Port Dover, and the Emblem of Bronte, also at the scene to rescue survivors, caught fire.

Captain Wright was among those picked up by Dulmage in his fishing boat, along with the first mate, and a passenger. The rest of the survivors were taken by the schooners to Kingston, where two were hospitalized for severe burns. By daylight, the Ocean Wave already had burned to the water’s edge and sunk with a roar as the water struck the red-hot engine boiler.

As was the custom at the time, the Ocean Wave was burning cord wood as fuel. Rumor was that the Ocean Wave had made up extra steam to maintain speed while racing a rival steamer. If so, the rival was not close enough to render any assistance. The fire started in the engine room while most passengers were asleep in their cabins. Nothing structurally was wrong with the vessel, which was practically new.

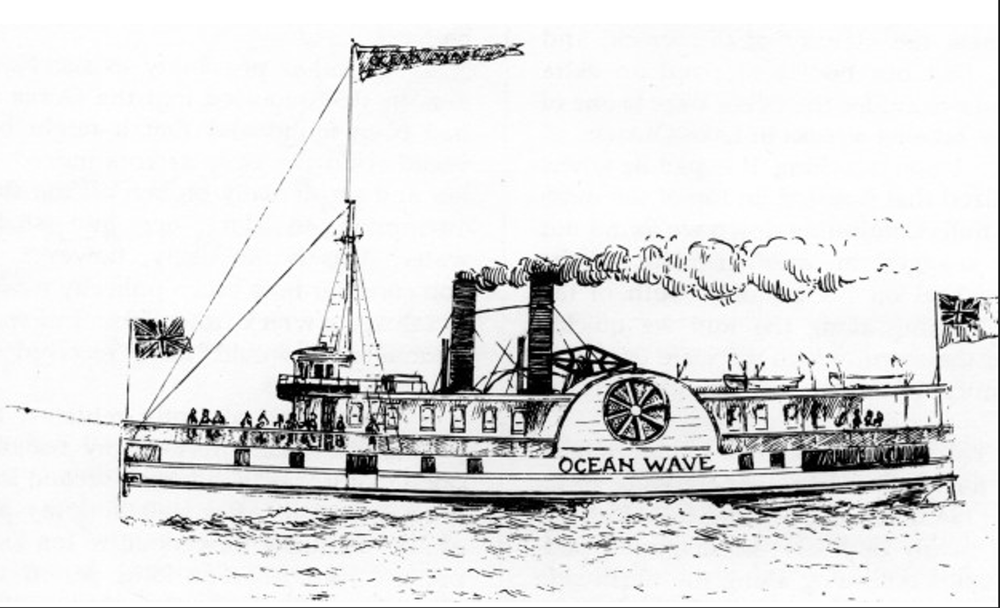

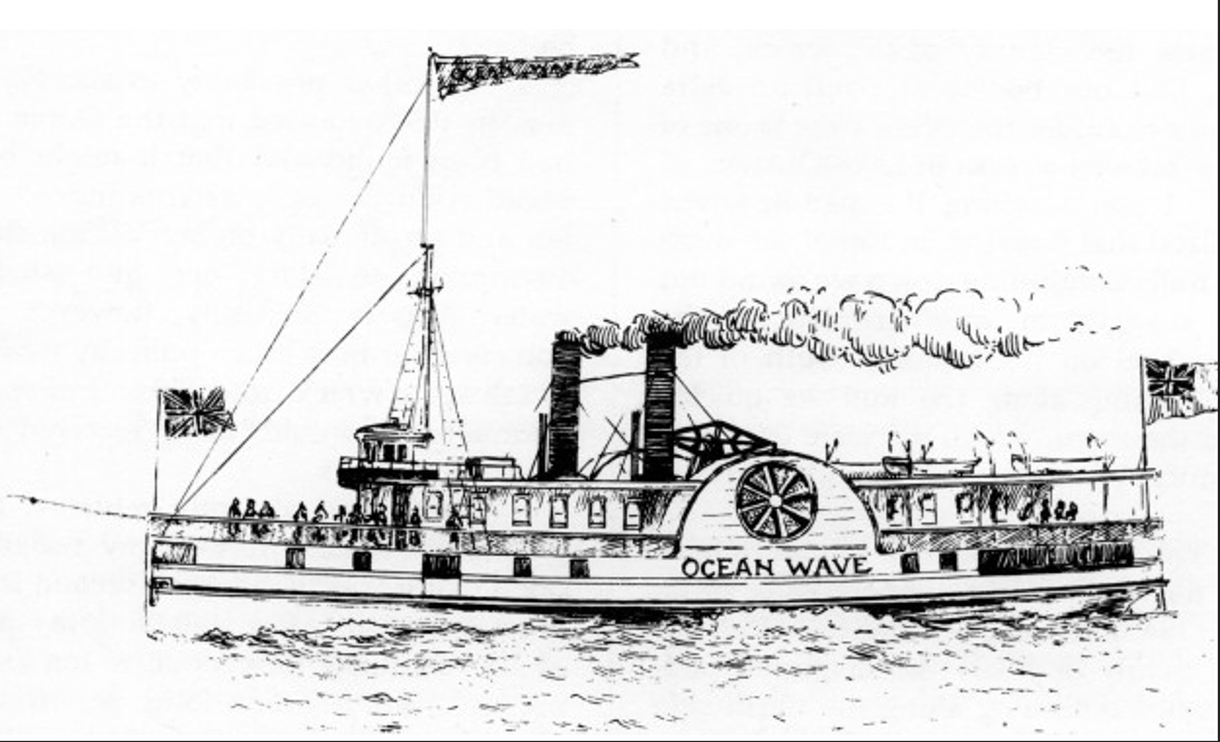

Ocean Wave had been launched on May 22, 1852 at the E.D. Merritt shipyard in Montreal. Of wood construction, she was 174 feet 4 inches long, 26 feet wide, 11 feet 6 inches depth, and registered at 241 tons. She had a vertical beam engine and was a side paddlewheel. Originally of British registry, the Ocean Wave was owned by the Northern New York Railroad, which operated between Ogdensburg and Malone, NY. She had 26 staterooms, 52 beds, and carried three lifeboats on the upper, or hurricane, deck. Although there was fire fighting apparatus aboard the Ocean Wave, much of it was inaccessible at the time, due to the flames.

Standing by the wheelhouse, George Potter, the second mate, happened to glance back over the hurricane deck. Framed by the two massive paddle-wheels, the walking beam rhythmically rocked back and forth. At one end a rod connected to the piston rose out of the depths of the ship; at the other, the connecting rod plunged back down to the crank that turned the shafts of the paddle-wheels. Potter thought he could see something around the connecting rod.

"What light is that?" he asked wheelman James Stead. Without waiting for a reply he strode aft across the deck. Almost immediately, fire puffed up through the opening in the deck. Just as the purser had done with a small deck fire earlier that spring, Potter sprang to the nearby fire buckets and immediately emptied two or three on the fire – to no avail. Potter needed help and he knew it. He ran forward to the wheelhouse and blew several blasts on the whistle to alert the crew. There was much terror and confusion amidst the cries of children and the shrieks of adults. Captain Wright tried to extinguish the blaze but without any success. He then jumped overboard, but not before being severely burned. Survivors were picked up by passing boats.

The fire began in the engine room and spread up through the smoke pipe, before being discovered by the first mate. Within 10 minutes, all three lifeboats had been destroyed by fire. They tried to run her ashore, but the fire was so great that it drove the helmsman from the wheel. The engines were still running, but the engineer couldn’t go below to stop them. With no steering, they were running in a wide circle, when the engines stopped, leaving Ocean Wave at the mercy of the winds and waves and away from the shore. Spurring on the fire was a cargo of 300 kegs of butter in the hold adjacent to the engine room. Other freight included 1,800 barrels of flour, 64 barrels of pearl ash, 60 to 80 barrels of seed, and an unspecified number of hogshead barrels, containing pork and ham. Eyewitnesses recalled that it “flamed up like a torch.” Melting, the butter quickly spread in flaming streams all over the lower deck. With nowhere to escape, many perished in the liquid fire. One story told was that the purser’s safe contained a large quantity of gold and silver, which went down with the ship but was never found.

There had been previous hints of trouble. On her initial trip, the felt lining that encased the steam-drum caught fire. Fortunately, there was a fire company aboard that quickly extinguished the fire by dousing it with 50 buckets of water and cutting away the burning felt. Then at 1 a.m. one morning in the spring of 1853, the purser, Thomas Oliver, noticed a spark catching hold on the hurricane deck. He quickly doused it with water from a fire bucket kept nearby. When later questioned, he brushed it off. "It could hardly be said she was on fire," he said. Sparks were frequently spotted flying out of the felt-encased door used for cleaning the boiler.

Erroneous reports appeared in some newspapers that the small propeller steamer Scotland had passed the wreck without rendering assistance. It later came out during the coroner’s inquest that the by the time she arrived at the scene of the wreck, her assistance was not needed, so the Scotland turned away and left. The coroner’s jury concluded:

Judging by the evidence, it appears perfectly plain that there was nothing in the nature of the accident to the Ocean Wave which rendered it inevitable, nothing which might not have been prevented by proper precautions. Sparks fell from the chimney, and the fire not being observed, the boat was destroyed.

In the fall of 1991 and the spring of 1992, two separate teams of divers searched the wreck of the Ocean Wave. Neither team found bodies, safes, or significant amounts of artifacts. At a depth of 154 feet, the Ocean Wave is too deep for recreational diving, however she has been visited by technical divers. It is a protected site.

References

- Lewis, Walter and Rick Neilson. "Life and Death on the side-wheel steamer Ocean Wave; FreshWater, 1992, Vol. 7 No. 1 (published by the Marine Museum of the Great Lakes at Kingston)

- Metcalfe, Willis. Canvas and Steam on Quinte Waters, South Marysburgh Marine Society, 1979, pp 103-104

- “Destruction by Fire on Lake Ontario of Steamer Ocean Wave on Lake Ontario.” New York Times. May 2, 1853

- “Destruction of the Ocean Wave By Fire.” Oswego Daily Journal. May 2, 1853

- “Terrible Calamity on Lake Ontario.” Oswego Daily Times. May 2, 1853

- “Loss of the Steamer Ocean Wave.” Oneida Weekly Herald. Utica, NY, May 2, 1853

- “Loss of the Steamer Ocean Wave by Fire.” St. Lawrence Republican. Ogdensburg, May 3, 1853

By Richard Palmer

Richard Palmer is a retired newspaper editor and reporter, and he was well known for his weekly historical columns for the “Oswego Palladium-Times,” called "On the Waterfront." His first article for TI Life was written in January 2015, and since then, he has dozens of articles and more. He is a voracious researcher, and TI Life readers certainly benefit from his interests.

Appreciation to Michael Macdonald who produces various wreck diving videos from scuba diving and other activities. See his work at www.youtube.com/@mmacado