Historic Shipwrecks of the Thousand Islands

by: Dennis McCarthy

Introduction

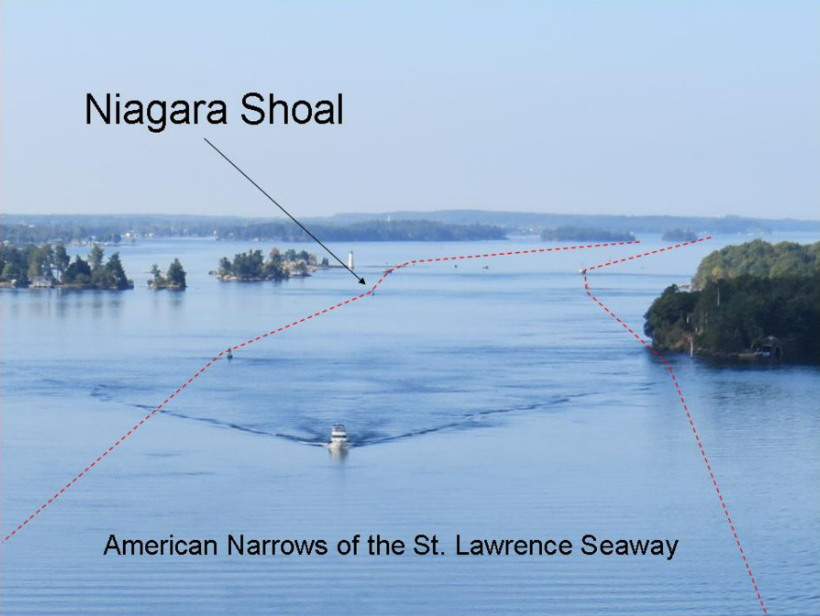

The Thousand Islands is the name of the group of islands that straddle the Canada/US border in the St Lawrence River, as it emerges from the northeast corner of Lake Ontario. The islands stretch for over 50 miles from Tibbetts Point near Cape Vincent, NY, to Ogdensburg, NY. The Canadian Islands are in the province of Ontario. The US islands are in New York State.

Today, the Thousand Islands are known for their lighthouses, historic castles, maritime museums, world-class fishing, and some of the best freshwater scuba diving in North America. The great St Lawrence Seaway winds its way through the Thousand Islands, making it part of one of the most important and famous waterways in the world.

The St Lawrence River serves as the main water route to access the North American interior and Great Lakes System. During the 18th century, two major conflicts played out in North America. The waters of the Thousand Islands were critical for movements of armies, ships, and supplies. The French control of this access was contested by Britain during the French and Indian War and defended by Britain from its American colonies in the War for Independence.

During these periods of conflict, the Lower St Lawrence was only navigable from the Atlantic to Montreal. The Upper St Lawrence was impassable for large vessels because of several rapids from Montreal to the edge of the Thousand Islands below Ogdensburg, NY. All goods, trade, supplies, and people coming and going to the upper Great Lakes from Montreal had to pass through the Thousand Islands.

From 1754 to 1760, the British and French built over 18 major warships on Lake Ontario and the Thousand Islands. By 1765, all of these ships had been lost, sunk, castaway, burned, or abandoned. Only about a dozen more major vessels were built before the end of the century; they too met similar fates.

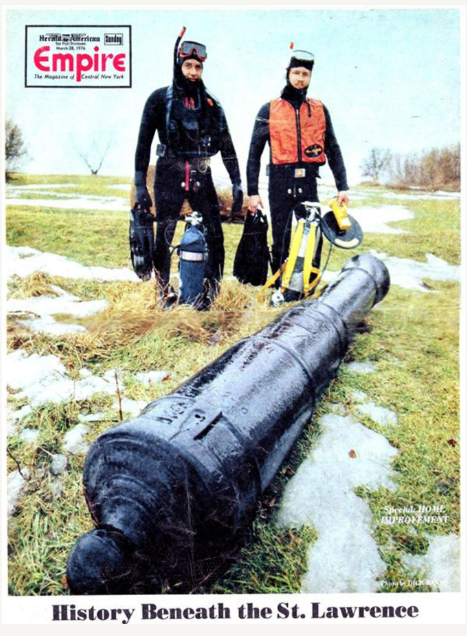

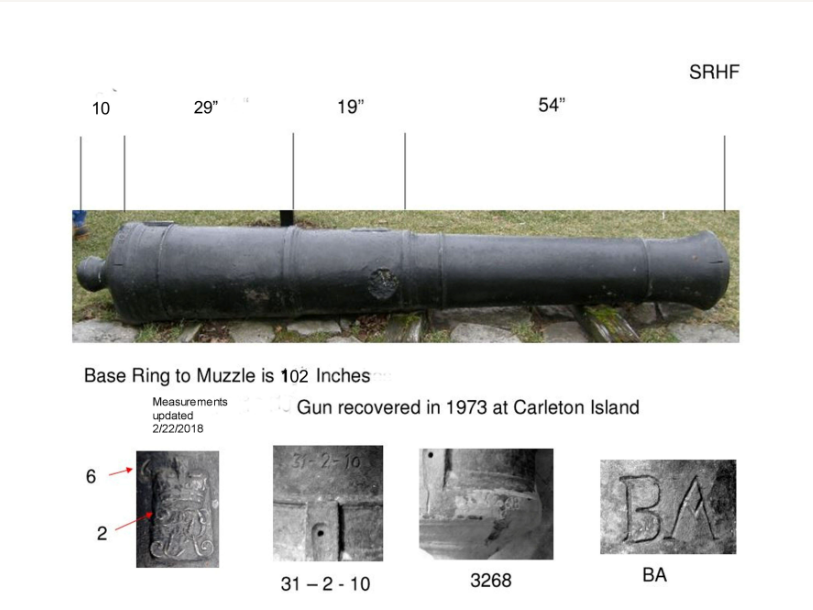

L: Figure 1: Scuba divers with an iron gun recovered from North Bay Carleton Island in 1972. [Herald American and courtesy of Syracuse.com]; R: Figure 2: Iron guns recovered from North Bay Carleton Island in the early 1960s. [Photo courtesy SRHF]

Discovery

In 1972 two scuba divers, using underwater metal detectors, found a cannon and a large iron reading, (Figure 1) from North Bay Carleton Island. This was in the waters off Carleton Island, where from 1778 to 1783, one of the most strategic British military posts in what was then called Quebec (renamed to Upper Canada in 1791) was located (Appendix A). These discoveries set in progress a series of events that resulted in the identification of two 18th century shipwrecks, some of the oldest shipwrecks in the Great Lake system.

The 1972 discovery was a British 12-pound cannon with a weight of 31-2-10 (Figure 2). Two 11 foot long culverins [1] had been found near the same location about 10 years previously (Figure 3).

Those and the 1972 discovery were part of a group of five guns abandoned by the British Army in 1808. With the fear of a coming war, the British Army removed five unserviceable iron guns left at the abandoned base on Carleton Island and placed them out of use by the Americans. For over 150 years, they remained on the bottom of the St Lawrence River just off Carleton Island, until their discovery by scuba divers.

The significance of the 1972 finds was that a metal detector was used in the detection of the cannon that was almost completely buried in the mud and a previously unknown large iron mass in a known shipwreck. The divers, who were members of the New York State Divers Association (NYSDA[2]), developed a working relationship with the New York State Office of Parks and Recreation during the cannon recovery.

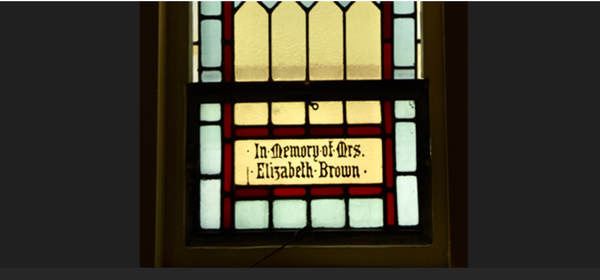

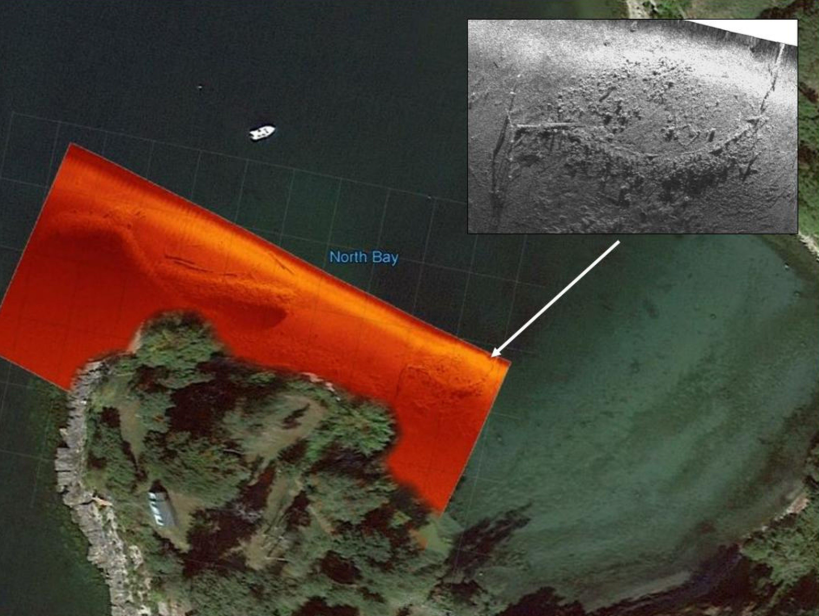

After the cannon recovery, they also proposed the recovery of a large iron target that had been located in the center of the wreck and the possibility of excavating the wreck itself. The availability of low cost efficient underwater metal detectors caused concern for future protection of the site. The shipwreck, known at the time as the ‘North Bay Wreck,’[3] first showed up on a map of Carleton Island drawn in 1810 by a British Lieutenant Colonel A. Gray (Figure 4).

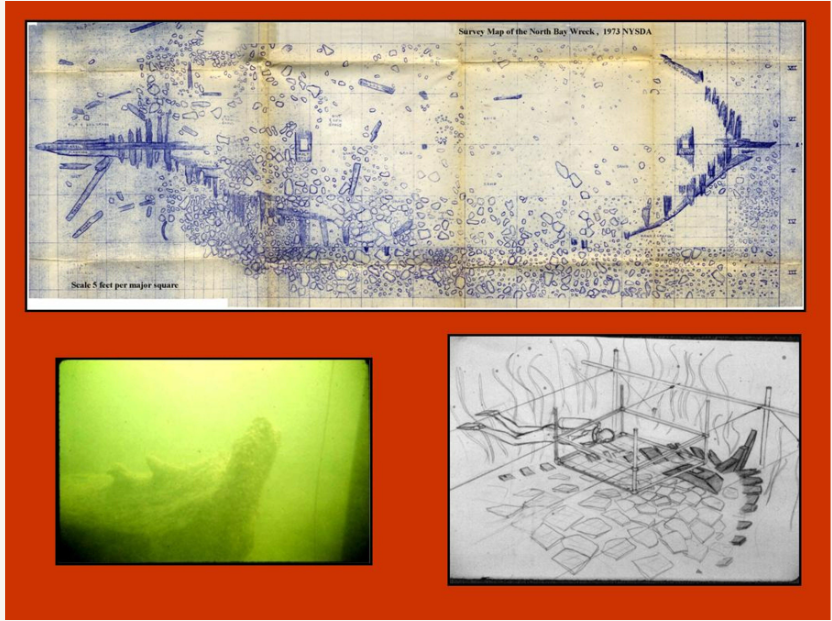

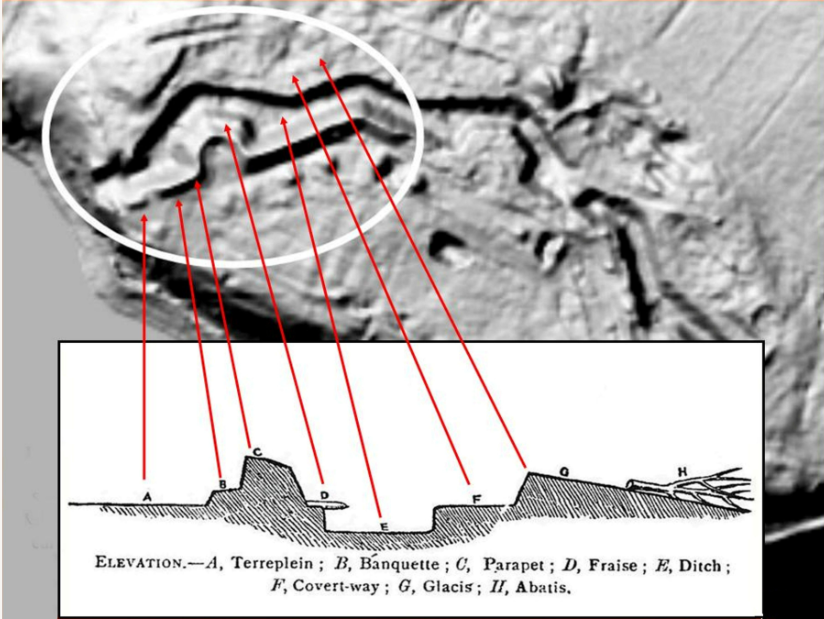

NYSDA organized an underwater archeology committee (NYSDA UAC). During the summer of 1973, the NYSDA UAC developed a proposal that served as a basis for the wreck research, excavation, and recovery of artifacts. The first phase of the site evaluation was the placing of a wire grid structure over the site, followed by detailed drawings of individual squares until the entire site was mapped. This produced a drawing of what was exposed and allowed detailed measurements of the ship’s key features (Figure 5).

In the March 1974 Annual Meeting and Conference of NYS History and Waters, members of the NYSDA UAC presented a paper ‘Ships and Shipping On Lake Ontario before 1800,’ which outlined the NYSDA research committee’s work where the most probable identity of the North Bay Wreck was presented.

The vessel was identified as the Haldimand (Figure 6), a British vessel built in 1771 in the Thousand Islands at Oswegatchie or what is today Ogdensburg, NY. The Haldimand was decommissioned at Carleton Island in 1782 when a fire burned its sails and cordage while in winter storage. The vessel was condemned, and its guns and crew were assigned to small boats. Up to 1785, it was still listed on reports but there was no documentation of its sailing. By 1785 a large disabled vessel was identified as being at Carleton Island.

In 1974, NYSDA was granted a permit under provisions of New York State Education Law Section 233. The focus of this permit was to survey the wreck located in North Bay, Carleton Island and to a lesser extent, several underwater structures that were the remains of rock-filled cribs.

New York Office of Parks and Recreation set up a preservation lab in Sackets Harbor, New York to receive artifacts and put them through a preservation process. For the years 1974 and 1975, the ship was excavated during the summer. Artifacts were recovered, bagged, recorded and sent to Sackets Harbor. Photos were taken on-site of the artifacts as well as features on the wreck such as a hole that was chopped in the bottom near the stern indicating that it had purposely been sunk.

By 1976 the survey and excavation were complete. The artifacts and information from it supported the premise that the wreck was His Majesty’s Snow the General Haldimand [4/5]that was built in 1771.

An Unexpected Result

As a result of work done by the NYSDA UAC, information on several shipwrecks was also found.

One was a court of inquiry of the British vessel HMS Anson[6] that had been ‘castaway’ on an unknown ledge of rocks in the St Lawrence River in 1761 . By comparing information from the 1761 court of inquiry with a documented return of British ships on Lake Ontario from 1759 to 1778 [7/8], it was concluded that the court of inquiry had to relate to one of three possible ships .

These three were the French ships that had been captured by General Amherst in 1760 during the Battle of the Thousand Islands[9]. Additional documents were used to determine that the vessel which had run aground and been ‘castaway’ was the renamed French corvette Iroquoise[10, 11]. Information in the court of inquiry about the location of the ‘castaway’ was so detailed that anyone familiar with the Thousand Islands could identify the location of the incident to an area known as the American Narrows, a dangerous five-mile long channel of the St Lawrence River which has had more sinking and groundings of ships per mile than anywhere else in the St Lawrence Seaway.

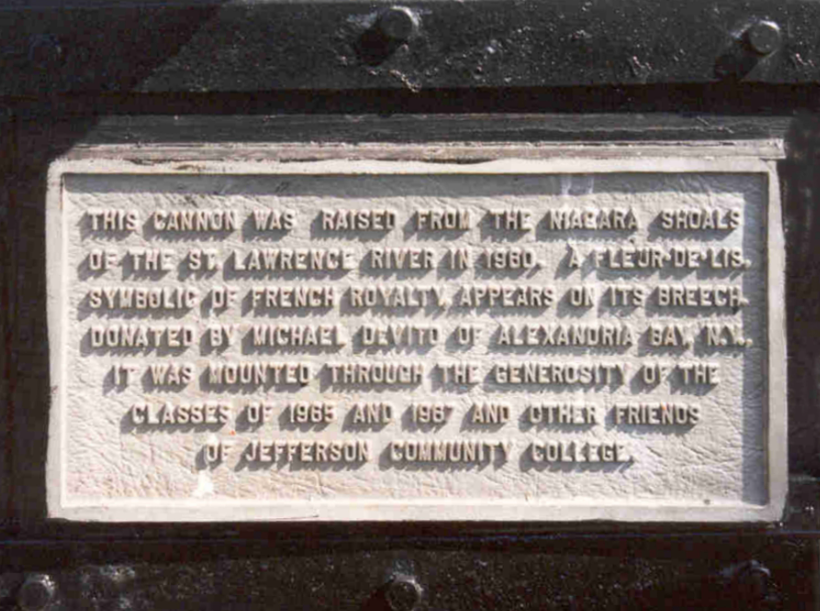

L: Figure 8. French 4 pound cannon on display at Jefferson Community College 1978. (SRHF); R: Figure 9. Plaque identifying Niagara Shoal as the location where the cannon was raised. [Photo courtesy SRHF]

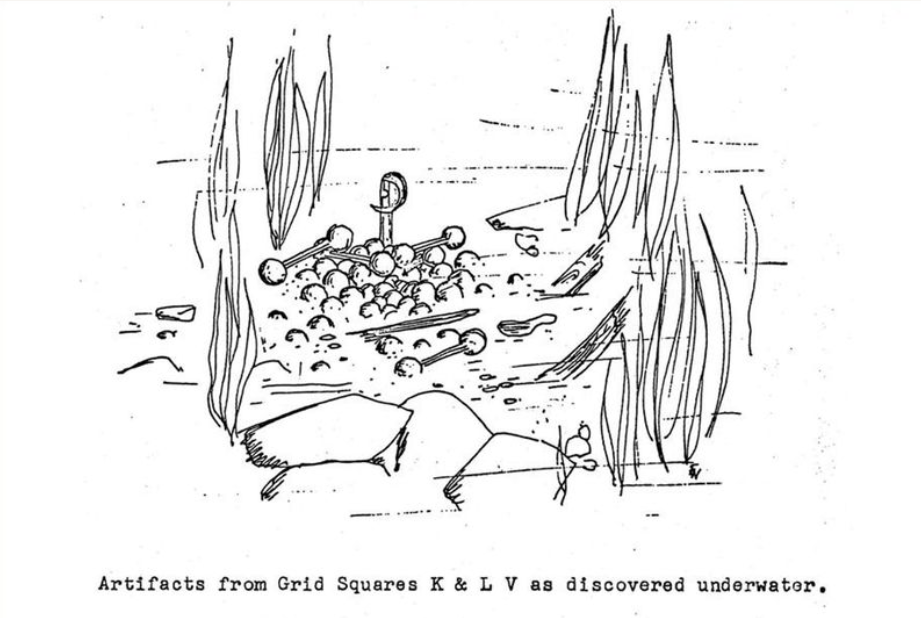

Some of the past members of the NYSDA UAC decided to see if they could locate the wreck from information from the court of inquiry. They discovered that in 1960, divers removed 3 cannons from a wreck on Niagara Shoal. Two of the cannon were French and one a British GR2. All the guns were 4-pounders and not serviceable (Figure 7). One of the cannons was donated to Jefferson Community College in Watertown, NY, and is on display at the campus (Figure 8). A plaque, part of the display of the gun indicated it was recovered from Niagara Shoal in the St Lawrence River (Figure 9). This location fits the description of the ledge of rocks given in the 1761 court of inquiry on the loss of the HMS Anson. All of the ordinances were without trunnions and the British gun was filled with five cannonballs to increase its weight. In 1759, when the Iroquoise fired for several days on British forces sieging Fort Niagara, her frames opened and had to have iron guns placed in her hull for support.[12]

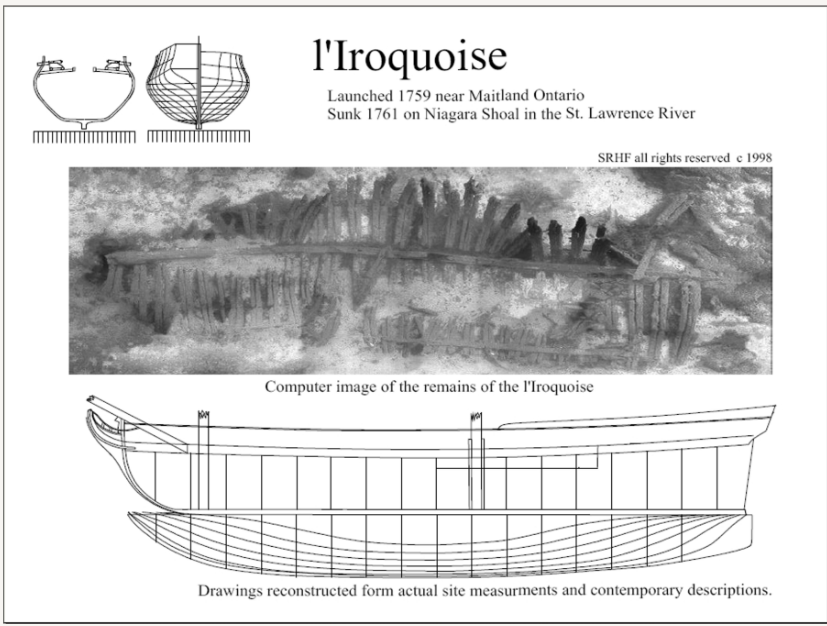

In the early 1980s, the vessel was lying in 65 feet to 80 feet of water, next to, but not under, the main shipping channel of the St Lawrence Seaway (Figure 10). At the time, with scant visibility and forceful currents at the site, the shipwreck was very difficult to dive. A limited survey of the vessel showed that it was in a deteriorated state. Only the very lowest portion of the vessel remained (Figure 11). The wreck, burned to the waterline when abandoned by the British in 1761, was an open hull with the siding still on the frames.

In 1993, an archaeologist from the Ontario Ministry of Culture and Tourism, Canada, visited the site (Figure 12)[13]. The Anson/Iroquoise, potentially the oldest identified shipwreck anywhere in the Great Lakes System, was at that time not considered significant to the United States. As the historical record documented the loss of the Anson/Iroquoise, it was of interest to the Province of Ontario if for no other reason than to identify if it were in the US or Canadian part of the Thousand Islands.

L: Figure 11. 1994 photo of the Iroquoise; M:Figure 12. Ontario Ministries survey boat Blue Fin anchored on Niagara Shoal in 1995. [Photos courtesy SRHF];R: Figure 13. Iroquoise site plan and computer-generated wireframe map.

In 1994, the divers that had been past members of the earlier NYSDA UAC formed the St Lawrence River Historical Foundation Inc. (SRHF) as a non-profit corporation.

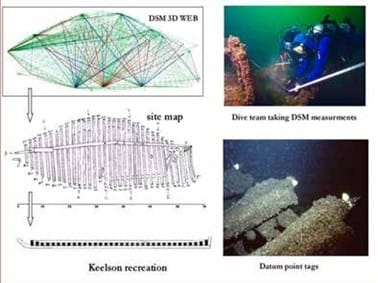

In 1995, SRHF applied to the NYS Museum and received a NYS Section 233 permit allowing them to study the wreck. With the name Iroquoise Project, SRHF set out to confirm through non-contact methods that the wreck on Niagara Shoal was the Anson/Iroquoise. All work on the project was on a volunteer basis, without compensation. The Direct Survey Method (DSM) [14] of measurement for mapping the exposed structure of the wreck was selected for documenting the site (Figure 13).

By the end of the 1997 diving season, 35 US and Canadian volunteer divers had made over 200 dives on the Niagara Shoal site. Several hundred DSM measurements had been taken. The entire wreck site had been videoed and photographed. Exposed portions of the wreck including fasteners, wooden frames, and keelson were measured and recorded.

A database was developed of the historical documents relating to the Anson/Iroquoise. Artifacts removed by divers in 1960 were located and documented. DSM information was used to update the project site plan, and a photo mosaic was created from still photos of the site. The updated site plan indicated that the basic measurement systems used in construction of the ship was that of pre-French Revolution Carolingian system. The photo mosaic provided an overall picture of the Iroquoise that could not be seen with the limited visibility of the water. With this information in place, SRHF was able to declare the Niagara Shoal Wreck was the Iroquoise/Anson lost in 1761.

This brought closure to the story of an important and unique shipwreck that is part of the history of four countries: France, Great Brittan, Canada, and the United States (Figure 14).

Cairn made out of Bar Shot and Lake Ontario Royal Shipyard

The iron target found in 1972, located on the wreck, was one of the first artifacts recovered (Figure 15). Not just one object but a very precisely placed group of objects. It consisted of a British naval cutlass of late 18th century pattern with some cannonballs (round, bar, and grapeshot) buried in the sand amidships of the vessel. The ordnance, primarily a group of bar shots, was arranged in the shape of a monument with a navel cutlass placed down the center of the pile (Figure 16). Not fully understood or questioned at first, it still presents an interesting question as to why a ship that was scuttled and filled with large rocks, bigger than what would be used for ballast, would contain what appeared to be a memorial. The wreck is located as an extension of the large 20 foot wide, 130-foot long, pier that is constructed of hand hewed log cribs filled with rock (Figure 17). If the monument was placed in the hull when the ship was first scuttled after the hull wood deteriorated, it would have flooded the wreck.

This would have left it underwater so that it remained undisturbed until divers found it. Carleton Island stayed the main naval base on Lake Ontario until 1786, when the base was relocated to Kingston, ON. How, when, and why what looks to be a monument was placed on the wreck with valuable ordnance and a navel cutlass is a total mystery. What or who would this honor?

The HMS Ontario was built at Carleton Island and launched in 1780. The Royal Shipyard where it was built was just yards away from where the Haldimand had been scuttled (Figure 18). The Ontario sank in a storm in Lake Ontario on October 31, 1780. She was a 22-gun snow and, at 80 feet in length, the largest British warship on the Great Lakes at the time. The Ontario was commissioned to replace the aging Haldimand. On 13 October 1778, James Andrews was appointed Master and Commander in the Naval Armament on the Rivers and Lakes. His ship on Lake Ontario had been the Haldimand. He took command of Ontario in the spring of 1780 and went down with it in that same year.

L: Figure 15: Recovered iron target from 1972 (SRHF); R: Figure 16: Cairn made out of ordnance. [Noted by Dr. Joseph Murphy, Preliminary Report Underwater Archaeological Investigation Carleton Island 1976, 9 (unpublished)]

He left a wife and children at Navy Hall in Niagara. It has been suggested that with no burial, a monument left in a ship that Captain Andrews had commanded could have provided some closure for his family. Near the monument, a small box of personal items was recovered during excavation, as well as a set of pewter cups.

At this time the Anson/Iroquoise (1759-61) and Haldimand (1771-83) are the oldest identified 18th century shipwrecks in all of the Great Lakes systems. They were built in the Thousand Islands and still remain there. It was the discovery of an iron gun in 1972 that set off the series of events that identified both wrecks.

L: Figure 17: 1993 picture of the remains of the pier at Carleton Island (SRHF); R: Figure 18: 2019 Sidescan of North Bay, Carleton Island (orange) outbox showing remains of the Haldimand (b/w) (SRHF).

Appendix 1: Carleton Island

Carleton Island is located in US waters near the middle of the south channel of the St Lawrence River. It sits seven miles from Lake Ontario and about three miles from the village of Cape Vincent, NY. The island contains 1,274 acres of land.

Today, Carleton Island has no great political importance to either the United States or Canada. The situation was very different in the late 18th century. Both modern countries were originally colonies of Britain. Carleton Island occupied a strategic point between the Thirteen Colonies that declared their independence in 1776, and the loyal British Colony of Canada.

It was called Deer Island when first used by British merchants in the 1770s. The large vessels which sailed on Lake Ontario were poorly suited to navigating the St Lawrence River. Goods were brought up from Montreal in small boats to the island and then transferred to the larger lake vessels.

In 1777, a British army under General Barry St Leger used Deer Island as a staging area for the western part of the Burgoyne Campaign. After their defeat at Fort Stanwix, Deer Island was again used in their retreat. The Burgoyne campaign defeat in the Battle of Saratoga was the first major British defeat of the American Revolution. The British lost not only an entire field army, but access to the Mohawk Valley, which they’d used to supply their western posts at Niagara, Detroit, and other strategic locations.

To find a new supply route, the British looked to the St Lawrence River. In August 1778, the Governor-General of Canada, Frederick Haldimand, instructed Lt William Twiss of the Royal Corps of Engineers, to select a site at the Eastern end of Lake Ontario to play a role in the new supply route. John Schank of the British Royal Navy assisted Twiss.

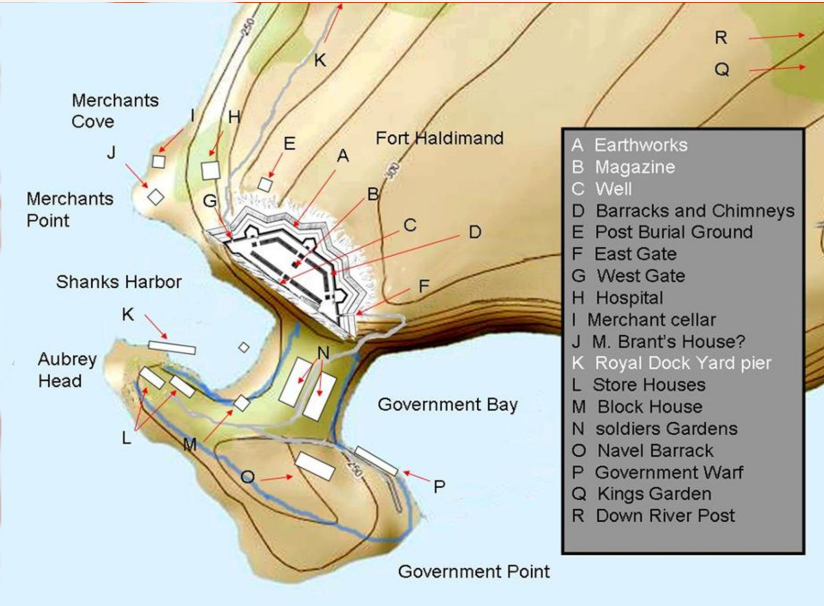

After reviewing both the abandoned French fort at Cataraqui (Kingston, ON) and Deer Island, Twiss and Schank selected Deer Island. Twiss renamed the island Carleton after Major General Sir Guy Carleton, the Governor of Quebec. Twiss outlined the design of the docks, shipways, hospital, fortifications, and barracks. After designing the major earthworks known as Fort Haldimand, Twiss returned to Quebec City, leaving men from the Royal Corps of Engineers to oversee the construction.

The British base at Carleton Island would continue to be important through the rest of the revolution. It served as one of the major staging areas for military actions against the Mohawk Valley. Its most important function was the transshipment of supplies to the western posts. It also acted as the headquarters for naval operations on Lake Ontario and the Upper St Lawrence River. The shipyard built two major vessels as well as several gunboats and maintained the Lake Ontario fleet.

By 1782 the entire west end of the island was occupied (Figure 19). Records indicate that at times, over a thousand merchants, camp followers, soldiers, sailors, Indians, and displaced loyalists lived on the island.

When the Treaty of Paris ended the American Revolution in 1783, the British army abandoned new activities on Carleton Island. Though major hostilities were over, a new need arose to resettle loyalist families who were displaced from the Mohawk Valley. To this end, the British re-occupied both the post at Oswego and the old French post at Cataraqui, which was renamed Kingston.

The British occupation of Carleton Island continued to decline. In 1785, transshipment for government stores was relocated from the island to Kingston. In 1788, the naval yard was also relocated. Technically, the island was ceded to the US by the Jay Treaty in 1796, yet in reality, Britain still held Carleton Island at the outbreak of the War of 1812. The base, once one of the most vital sites in the province of Canada (1778 to 1783), was eventually ceded to the US as the only land change resulting from the War of 1812.

For the first half of the nineteenth century, the bays at the head of the island played a role in the lumber trade. In 1898, a grand Villa was constructed at the island’s head during the Golden Age of the Thousand Islands. Most of the island was used primarily for cattle grazing until land development in the 1980s.

Carleton Island today is entirely privately owned. There is no historical society or museum dedicated to the British military occupation of Carleton Island. Over 25 acres of the west end of Carleton Island is on the National Register for Historic sites (Figure 20).

By Dennis McCarthy

Dennis R. McCarthy lives in Cape Vincent, NY, along with his wife Kathi. He is a graduate of the Rochester Institute of Technology, with a degree in Electrical Engineering. Dennis has been diving since 1971. He co-founded the St Lawrence Historical Foundation Inc. in 1994 and currently serves as one of its directors. His memberships include the Nautical Archeological Society (where he holds an NAS 2 certification) and the Ordnance Society of Great Britain. He is a past president of the Clayton Diving Club. Both Dennis and Kathi serve on the board of the Cape Vincent Historical Museum and are past members of the Advisory Council for the Proposed NOAA Lake Ontario Sanctuary.

See past articles by Dennis McCarthy here and here.

Editor’s Note: This article was written originally as a paper presented in 2019 at Portsmouth, England, at The Nautical Archaeology Society and the Ordnance Society co-hosting conference, examining how ship and ordnance remains found on land and under the sea help us understand our maritime past. It is the story of the iron guns found at Carleton Island and Niagara Shoal. The paper was published in 2020 by the Ordnance Society in their journal. See their website: The Ordnance Society | Ordnance & Artillery of All Periods. With permission of the author, it has now been updated and reprinted in TILife.

Footnotes

[1] A culverin is a medieval cannon of relatively long barrel and light construction. It fired light (8 – 16-pound [3.6 – 7.3-kg]) projectiles at long ranges along a flat trajectory. The culverin was adapted to field use by the French in the mid-15th century and to naval use by the English in the late 16th century.

[2] NYSDA is a non-profit organization dedicated to promoting and protecting the sport of skin and scuba diving, organized in 1961.

[3] Dennis McCarthy, "Carleton Island’s North Bay Wreck" (Quarterly Journal of the National Museum of the Great Lakes, 2019, Volume 75), Page 151-163.

[4] Official name His Majesty’s Snow the General Haldimand, she was referred to in regular communications as the Haldimand.

[5] A Snow is a square rigged vessel with two masts, complemented by a trysail-mast stepped on the quarterdeck immediately behind the main mast. See Falconer, W. 1769, ‘An Universal Dictionary of the Marine London,' page 271.

[6] Amherst Papers WO34/19 Page 199-212 ‘Proceeding of the court of Inquiry ... Anson Schooner’ December 1st, 1761 at Oswego

[7] Haldimand Papers MG 21, Add. Mss. 21805, (B-145) Page 91 ‘Return of His Majesty’s vessels on Lake Ontario 22, October 1783’ (Misc. Papers relating to the Provincial Navy)

[8] Haldimand Papers MG 21, Add. Mss. 21804, (B-144) Page 99 ‘Return of all the Vessels … from the year 1759 to this date’ (July 1778)

[9] The 1760 Battle of the Thousand Islands involved five warships and over 11,000 British, French, and Native American soldiers and was fought off Chimney Island at the west end of the Thousand Islands.

10) M. Hughes, 1979, ‘Our Search For The English Schooner Anson/French Corvette Iroquoise,’ State University of New York, Empire State College. http://home.netcom.com/~srhf/ SRHF_hughes.html (accessed 12 February 2020)

[11] His Majesty’s Schooner the Anson, Late the Iroquoise (Quarterly Journal of the National Museum of the Great Lakes, 2017, Volume 73), Page 98-108

[12] C. Snider, 1958, ‘. . . has opened a butt in the waist on the starboard side. I have obliged to put two pieces (of ordnance) into the hold . . .’ Tarry Breeks and Velvet Garters, Toronto, Ca, 104

[13] Peter Engelbert was a staff archaeologist from the Ontario Ministry of Culture and Tourism.

[14] N. Rule, 1989, ‘The Direct Survey Method (DSM) of underwater survey, and its application underwater.’ The International Journal of Nautical Archaeology, Volume 18, Issue 2 May 1989.

Additional Sources

- Haldimand Papers MG 21, Add. Mss. 21805, (B-145) Page 91 ‘Return of his Majesty’s vessels on Lake Ontario 22, October 1783’ (Misc. Papers relating to the Provincial Navy).

- Demerliac, A. 1995, ‘La marine de Louis XV : nomenclature des navires français de 1715 à 1774,’

- Letter from Alain Demerliac to SRHF February 3, 1997.

- For more information on Frederick Haldimand, Lt. William Twiss, John Schank, and Sir Guy Carleton, see the Dictionary of Canadian Biography at http://www.biographi.ca/en/ (accessed 12 February 2020).

Further reading

Andrews R 2004 ‘Two Ships - Two Flags: The Outaouaise/Williamson and the Iroquoise/Anson on Lake Ontario, 1759 – 1761’, Canadian Nautical Research Society ‘The Northern Mariner’.

Andrews R 2015 The Journals of Jeffery Amherst, 1757-1763, Volume 1 & 2, Michigan State University Press.

Dunnigan B (ed) 1994 translated by Michael Cardy Memoirs on the Late War in North America between France and England by Pierre Pouchot, Youngstown, NY.

Casler N 1906 Cape Vincent and its History. Hungerford – Holbrook Co., Watertown, New York.

Durham J 1889 Carleton Island in the Revolution. C W Bardeen, Syracuse, New York.

Ford B 2017 The Shore is a Bridge The Maritime Cultural Landscape of Lake Ontario, Texas A&M University Press, College Station.

Fryer M 1980 King’s Men the Soldier Founders of Ontario. Dundurn Press Limited, Toronto.

Grouse G 1949 Partridge Shortening, Self-published, Limited edition 100 Copies.

Comments submitted after publication:

"Well done and really interesting . The history of that area is enormous and important. Thanks for your research." Doris Albert

"My grandparents, Harry & Hattie Higgins, lived on a farm on Carleton Island. I don't remember the number of acres. Part of their livestock was turkeys. They also boarded the teacher who taught at the schoolhouse on the island. That is how my mother and father met. Mom was the teacher; Dad was the son of Harry & Hattie. They were married in October 1929." Aldis Klavins