[Note: Rideau is pronounced like Lido]

As much as my wife and I like staying put when in residence at Comfort or Grenadier Island, there are occasions when we want to go on an excursion. There is a wealth of interesting and stimulating places to visit an hour or two from the 1000 Islands. We have taken many short trips over the years and we are always looking for new ideas for places of visit. I contacted Susie Smith about my idea and discovered she has also considered a resource section in TI Life as a worthy extension to the publication. I am honored to provide an initial entry into the new “Excursions” section of “Thousand Islands Life.com.”

The Rideau Canal:

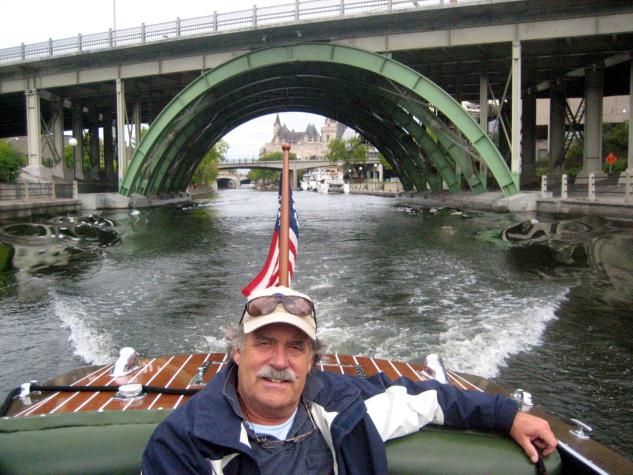

Natural beauty is a venue that can’t be faked. The Rideau Canal Waterway is a stretch of Canadian wilderness that exhibits incredible landscapes and amazing ingenuity. A series of more than 40 locks and 200 kilometers (125 miles) of waterway takes a boater from the Ottawa River in Ottawa to Kingston where Lake Ontario flows into the St Lawrence River and the 1000 Islands begin.

Boating is not the only way to enjoy this attraction. Many of the lockstations are easily accessible by car and have exhibits to educate the visitor and enhance the experience. Picnic areas are a standard amenity while towns like Merrickville, Smith Falls, and Ottawa have restaurants nearby as well. Other lockstations providing exhibits include Jones Falls, Kingston Mills and Chaffey’s Locks. Most of these attractions are best visited between mid-May to mid-October when the locks are in operation.

(more information is available at websites including: )

History:

Following the War of 1812, the British were seeking a way to connect Upper and Lower Canada without the risk of encountering American forces on the St Lawrence River. The Duke of Wellington, who gained permanent fame defeating Napoleon at Waterloo, advocated building what was to become the Rideau Canal Waterway. Surveyors were hired and in 1826 Colonel John By was assigned by the British Royal Engineers to oversee the construction of a navigable corridor between Lake Ontario (Kingston) and the Ottawa River (Ottawa), Ontario. Two companies, 162 men, of the British army special construction corps known as Royal Sappers and Miners were sent to assist the building effort. Canada was still under the governance and protection of the British and would not become an autonomous nation for another forty-one years in 1867.

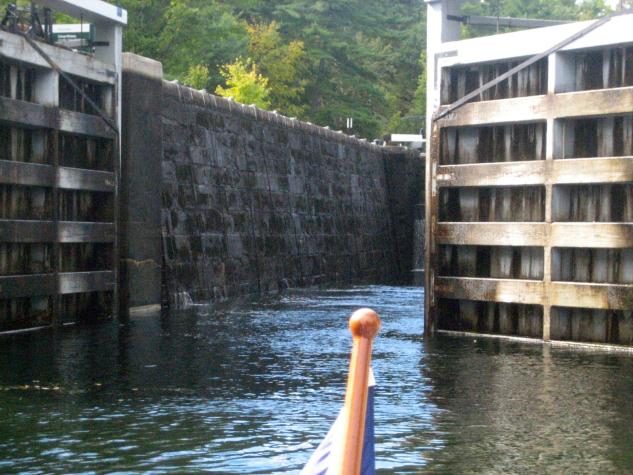

Most of the building effort was achieved by hiring thousands of laborers and tradesmen from the general population. Colonel By designed the waterway to operate as a slackwater system which relies on flooding to raise water levels to a navigable depth of five feet in the case of the Rideau Canal. The task of connecting lakes and tributaries into a 125 mile corridor was a monumental task that required building 47 locks. Each lock was to be 134-feet in length and 33-feet wide. In addition to the 47 locks, 52 dams had to be built and two channels had to be excavated.

The channel between the landlocked lakes at Newboro proved to be one of the most obstinate problems. This stretch of land is at the high point for the lock system and was known as the “Isthmus”. Contrary to the belief at the time of surveying, this soil was comprised of solid granite rather than dirt and loose rocks. Because early explosives were unstable and unreliable, blasting into bedrock was both difficult and dangerous. William Hartwell, the original contractor, asked to be released from his contract when it became apparent that this channel was going to be far more complicated and time consuming than anticipated. After consulting with additional contractors and engineers, Colonel By determined that the solution to completing this section was to raise the water level more than originally planned and thereby reach a navigable level without the ordeal of removing more of this bedrock. The arch dam at Jones Rapids, the coffered dam at Hogsback Rapids, and the canal cut connecting Lower Rideau Lake and the Rideau River were other engineering works of art.

Irish, Scottish, and French-Canadian workers were important constituents of the work force. Malaria was serious problem that contributed to more deaths than construction accidents and overall an estimated 1000 workers and numerous associated family members died during the construction period. The Irish supplied the largest contingent of workers, comprising approximately 60% of the labor force, and they suffered the greatest number of fatalities. Celtic Crosses in Ottawa, Kingston and at Chaffey’s Lock commemorate the Irish immigrants who perished working on this enormous project. A.J. Christie who kept work force records during the construction years reported that a few deaths like that of Patrick Sweeney were unrelated to disease or construction mishap. Mr. Sweeney drowned while attempting to swim across the Rideau River to obtain another bottle of whiskey. The coroner stated in his 1831 inquest “When last seen alive, he was going down with a bottle or flask in his mouth.” This was extremely demanding work and it took a toll on a worker’s psyche as well as his body.

Much of the work was accomplished with pick, shovel and wheel barrow. Stones for the locks often had to be quarried miles away and then transported during winter by farmers utilizing sleds and oxen. Gates for the locks were constructed at the lock sites by blacksmiths and carpenters. Simple mechanical tools like lifting cranes assisted by horses or oxen were used to move stones and gates into place. A single gate might weigh as much as five tons.

The canal opened on May 24, 1832. It provided a secure line of supply between Kingston and Montreal. Four blockhouses were built at the strategic points of Kingston Mills, Newboro, Merrickville and the Narrows. Each of these structures had housing for approximately twenty soldiers but these blockhouses seemingly posed enough of a deterrent that they were never needed for the defensive reasons they were built.

Paul Schliesmann in his book “The Rideau Canal; A Historical Guide” characterizes 1835-1847 as the “golden age of transportation on the Rideau Canal… In 1848, Rideau transportation was dealt a heavy blow when the St Lawrence River canals opened. Boats could now take the more direct route from Kingston to Montreal”. Furthermore relations between the United States and Canada were far more relaxed than they had been when the canal system was built. As trains became more prevalent, the commercial value of the Rideau declined further. Scenic tours aboard luxury steamers became a popular pastime and landmarks like the “Duke’s profile” and “the elbow” received their titles during this era. After World War I roads were improved and became more plentiful and people began using cars to do their sightseeing.

Fishing lodges and the fishing guide business gained popularity in the late 1800s and fishing continues to be an important industry for the Rideau region today.

Today all manner of watercraft carpet the Rideau waterways. Kayaks, canoes, jet-skis, outboards, cruisers, sailboats, fishing boats and other boating alternatives converge at this scenic area where people enjoy what is truly a water paradise.

Tubing, swimming, water skiing, paddling, sailing, fishing and even hiking are among the many popular summer activities.

Interpretive centers and museums are popular venues during July and August, which is the height of the summer tourist season.

By Tad Clark, Comfort and Grenadier Islands.