Delays on the River: Winter, Ice, and the Ships

by: Michael Folsom

On winter mornings along the St. Lawrence River, sound carries farther than it does in summer. The hum of distant engines. The creak of ice shifting against steel. The low, patient thump of a ship that is not moving—but could, at any moment.

For generations, this River has taught us the same lesson: movement is seasonal and winter always has the final say.

Over the past several weeks, that lesson has unfolded once again, captured through countless observations of ships at anchor, ice tightening its grip, and a system easing toward its winter standstill. But to understand what is happening now, one must understand what has always happened here.

A River Built for Motion—and Delay

When the modern St. Lawrence Seaway officially opened in 1959, it was hailed as a triumph of engineering—an inland ocean highway linking the industrial heart of North America to the world. Steel mills, grain elevators, and ports from Duluth to Montreal reshaped their futures around it.

Yet from the beginning, winter was never defeated—only negotiated.

Unlike storms that announce themselves with drama, winter tightens its grip on the Seaway quietly. Ice first gathers along the shoreline, then creeps toward the channel. Eventually, the channel narrows, though weeks earlier it had carried steady traffic — commercial and recreational—between the Great Lakes and the Atlantic.

“It’s like a cork in the bottle,” was how the aggressive winter weather versus the massive steel hulled vessels was deemed in 2018, as a ship sat wedged in a US Lock for days due to ice buildup. The incident captured the attention of many near and far, while bringing truth to the fact that ships don’t stop because they want to; they stop because the River says it’s time.

Early Seaway planners knew the navigation season would always be restricted. Ice, not infrastructure, would dictate the calendar. The locks could be engineered. Channels dredged. But the River itself remained in charge.

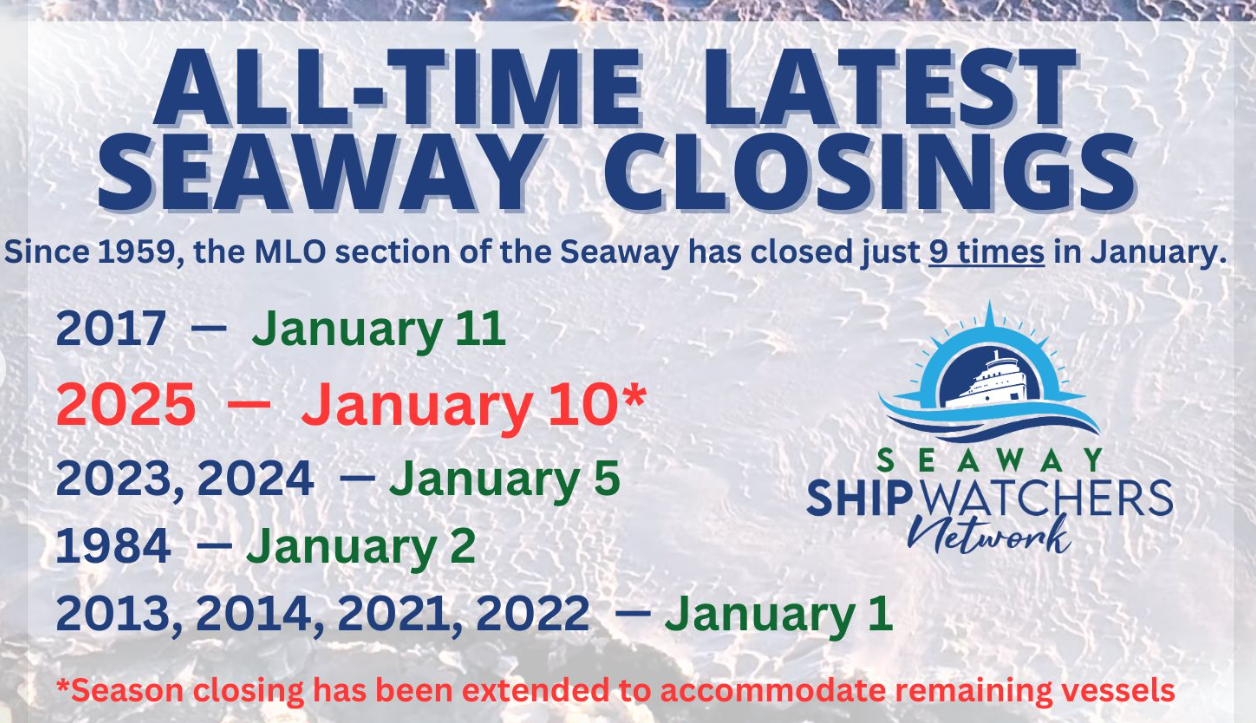

Historically, the Seaway has closed anywhere from late December to early January, depending on conditions. Some years offered grace; others did not. The 2025 season was no different. A closing date was set months prior to the end without a view of what was to come.

What ship watchers saw recently is not unusual — it is cyclical. Bitter cold, ice freezing temperatures are a given in northern New York and eastern Ontario every winter, and with those conditions come circumstances.

The Delays

This season’s slowdown began quietly. Temperatures dipped. Shore ice formed. Then anchorages filled.

As the holidays approached, chatter of condition changes began. By the New Year, navigation issues began to arise. In early January, vessels were being forced to hold position near Carleton Island, Prescott, Wilson Hill, St. Zotique, and Beauharnois ,while crews combatted growing ice fields that were jamming up locks and the South Shore Canal. The January 5 closing date was already pushing the envelope in terms of extending the season, but Mother Nature would be the one to dictate how it would conclude.

Icebreaking tugs would work all day and night from Christmas until the close. Crews from Ocean Groupe, a Canadian-based tugboat operator, would end up completing more than 3,000 man-hours during that span as they worked in the area of Beauharnois and the South Shore Canal, west of Montreal, vigorously trying to keep a path open for ship traffic. Often their efforts were met with a need to pivot.

The Canadian Coast Guard (CCG) would play a part in that stretch as well, while the teams at the US locks and aboard Seaway Guardian ensured that Massena didn’t see a repeat of 2018.

Throughout the process, lock personnel and Seaway authorities worked to coordinate movements with caution that bordered on choreography. Ice floes often dictated when a vessel could enter a lock, or the ice build up on the walls that needed to be scraped by heavy equipment would delay entry. Every decision balanced progress against safety, especially when temperatures hover well below freezing and ice responds unpredictably to wind and current.

At the peak, 10 ships would anchor near Cape Vincent and as many as 12 others spread across the lower St. Lawrence. Noelle G entered Carleton Island anchorage on January 2, and ice surrounded the ship after a few short days.

In earlier decades, information on the Seaway traveled slowly—radio chatter, dockside rumors, next-day newspapers. Today, ship watchers have been able to follow the fiasco in real time, with photographs and position reports turning individual vessels into shared points of attention, and the detail has allowed for everyone to better understand the circumstances.

Effects of the Delay

For River towns, the sight of anchored ships is as familiar as snowfall.

Residents along the St. Lawrence have always lived with the Seaway’s ebbs and flows. In winter, vessels become temporary landmarks—appearing suddenly from behind a snow squall, lingering unexpectedly in anchorage, then vanishing when conditions allow. Conversations turn to ship names, flags, and cargoes, just as they did decades ago when families gathered along the River to watch freighters pass.

What has changed is visibility. Social media has turned local knowledge into a shared experience. A ship that once mattered only to those nearby now draws attention from across the Great Lakes basin.

Each delay for a ship carries weight beyond the water. A single oceangoing vessel delayed by ice represents schedules disrupted across continents. Cargoes of grain, steel, or bulk materials depend on precise timing near season’s end. Crews face extended rotations. Ports adjust expectations. Winter does not stop trade — it compresses it.

Noelle G, the last ocean vessel to lift anchor at Cape Vincent carried cargo from the upper lakes headed for Great Britain. Its cargo was at risk of being significantly delayed from the original delivery date. Thanks to social media, ship watchers from Duluth, MN kept tabs on Miedwie, the final ocean vessel in that port, which was headed for Gibraltar with a load of durum wheat.

Historically, late-season transits have always been a gamble. Old logbooks tell of captains pushing north “one more run” before freeze-up, knowing the rewards and the risks. Today’s ships face the same calculation, though with better forecasting and fewer illusions about control.

The biggest gamble this season was the Seaway setting a closing date after the first of the year that wasn’t able to be met and thus become costly.

The End Until Spring

The latest closing in Seaway history will be a record now held by the 2025 season. Noelle G will go down as the final ocean-going downbound vessel, while Captain Henry Jackman and Algoma Equinox, along with CCG Judy LaMarsh paraded upbound as the last vessels of the season.

This year’s slowdown, well-documented by ship watchers across the region, was not a failure of the system, nor an anomaly of weather. It is the River and Mother Nature having control, always, and they will continue to do so when the ships awaken in the spring.

With the Seaway reaching full winter closure, the River grows quieter—but will never be completely inactive. Ice shifts. Plans change. Engines idle, at the ready.

The opening for the 2026 season is just over two months away.

By Michael Folsom

Michael Folsom has been covering the Seaway since 2008 when he first launched a blog known as “The Ship Watcher.” He has ties to the River, having worked for the Antique Boat Museum, created the popular Seaway Splash event in Clayton, served on local committees and Chambers, and calls Clayton his second home. He launched the Seaway Ship Watchers Network on social media in 2011 and has grown its following to nearly 100,000. His coverage has dubbed him a person of knowledge on the Seaway and commonly quoted by print and television media outlets on both sides of the River.

Editor's note: See also: "River advocacy group: Iced-in ships reflect need for shorter season, By CHRIS BROCK, cbrock@wdt.net, Jan 5, 2026.