Cholera on the St. Lawrence River and Lake Ontario

by: Richard Palmer

It was said that cholera originated in Asia and spread west rapidly by the trade routes. When the deadly disease arrived in Europe in the spring of 1832, emigrants flocked to Canada and the United States, fleeing the pestilence. In North America, the first cases showed up in Montreal in early June of 1832, via a ship carrying Irish immigrants. The public press had warned of its approach, but little was done to stop it. Every port in the region became alarmed. From Montreal, the disease moved rapidly down the Chaplain Valley, into the Hudson Valley, and westward up the St Lawrence River and Lake Ontario.

Communities were thrown into deep anxiety. The editor of the Oswego Palladium later recalled:

No one can now realize the panic that preceded the cholera epidemic of 1832.

The appearance of cholera was the signal for the general exodus of inhabitants of larger communities, who in their headlong flight, spread the disease throughout the surrounding countryside. As it surged through the Great Lakes region it caused widespread panic, devastating port cities like Buffalo, Detroit, and those along the Erie Canal. The disease largely spread through contaminated water, causing mass deaths from dehydration, sparking panic, quarantines, and blame, particularly towards immigrants, though it eventually subsided by autumn, setting precedents for future public health responses.

Cholera is an acute diarrheal infection caused by ingestion of food or water contaminated with the bacterium Vibrio cholerae. It can cause diarrhea, dehydration, and even death if it goes untreated. Luckily, it’s now fairly uncommon in the western world, although it’s still a high risk for people living in places with unsafe drinking water, poor sanitation, and inadequate hygiene.

Cholera in Oswego

Although Oswego was a lake port subject to an early attack of the scourge, it escaped almost wholly from its effects. Some said this was due partly to the topography of the village. But history records that it was largely due to the prompt and efficient measures adopted by the citizens to protect themselves.

Early in June, when it became apparent that the plague was on its way up the St. Lawrence, the village trustees met and adopted a resolution that a board of physicians be appointed to examine all vessels arriving, and to report on their condition to the trustees.

A strict quarantine was established and the village was literally sanitized, or what was said to be a “general sanitizing,” with all known precautionary health measures taken. Guards were stationed on the harbor piers to prevent vessels from entering. As several Canadian vessels arrived in Oswego, they were warned to “stand off.” But the Canadian steamer William IV, laden with passengers, seemed inclined to approach the harbor against the warning of the guard.

An old cannon, which had seen its best days, was placed on the bluff next to Fort Ontario as a further warning. When fired, it was only a "flash in the pan,” but William IV sailed off to avoid trouble. There were reports circulated that several fatal cases had actually developed in the village. But these were promptly contradicted by the Board of Health.

First reference to the so-called "cholera scare" found in village records is in the minutes of June 13, 1832. A communication from trustees of the village of Syracuse "giving notice of an alarm in relation to the approach of the cholera and urging the board to take precautionary measures against its introduction from the north" was received and read.

It was at once resolved "that a board of physicians be appointed who shall examine all vessels arriving at this port and report to the board immediately the situation of such vessels as it regards the health of those on board." Doctors Baker, Moore, Hand, Holland, and Hart were appointed as the board of physicians. Village President Matthew McNair was authorized "to employ necessary boats and men to detain without the harbor all vessels which may arrive here until same shall have been examined by physicians." Strict and stern punishment was to follow any who failed to obey any written order of the president, the Board of Trustees, or the Board of Physicians "in relation to anchoring or mooring or disposition of such vessel." Penalty was a fine of $50.

First Health Board

At a meeting of the village board, June 22, a report of a citizens' meeting the preceding day relative to "alarm on the subject of the cholera," which requested the board to sanction the proceedings of said meeting, and to pledge the credit of the village for defraying expenses incurred by the Board of Health appointed at said meting, was presented.

This board of health, probably the first in Oswego, consisted of Peter D. Hugunin, J. Grant Jr., R. Bunner, T.S. Morgan, P.S. Smith, J. Turrill, H.N. Walton, Dr. Baker, Dr. Moore, Dr. Hand, and Dr. Adkins.

Responding to the emergency call from this citizens' group, the village board added Dr. Hart and Dr. Howland to the Board of Health and pledged the security of the village "for the defraying of any expenses which said Board of Health may deem proper." At this same meeting of June 22, as a precautionary health measure, draining of the lowlands of East Oswego in the improved part was ordered.

Fund Raising Plans

Anxiety over the cholera continued, and on June 23, 1832, the village board took necessary steps for providing the funds needed for the erection of a hospital. A petition to the legislature, asking permission to raise $1,000, was authorized. Realizing there was little money, the board authorized McNair to loan the necessary sum and pledged the credit of the village.

The state legislature was called into extra session to deal with the cholera situation. An entry in Oswego village records shows that at a meeting of the village board on June 26, a certified copy of the law passed by the legislature providing for the appointment of a more official board of health. As a result, all members of the first Board of Health resigned, and a new board was named, which included Joseph Turrill, Rudolph Bunner, John Grant Jr., Horatio N. Walton, Theo S. Morgan, George N. McWhorter, and Elisha Moore. Dr. W.G. Adkins was named health officer. McWhorter resigned two days later, and Joseph Grant and Ambrose Morgan were appointed.

The question of whether the board had any right to pledge the security of the village for health then arose. Village board members showed their faith and interest by putting up their own private funds "as may be necessary to defray the expenses of the Board of Health not exceeding the amount one thousand dollars." At the next meeting, on July 2, 1832, President McNair reported he had negotiated a note for $300, and paid the proceeds to J. Turrill, Esq., chairman of the Board of Health.

Next, work commenced on “draining of stagnant waters, abatement of nuisances and other sanitary measures.” At a meeting on July 16, 1832, the board decreed that "after July 24th the ordinance prohibiting the running at large of swine the operation of which for some time had been suspended shall be in full force." One precaution Oswego residents were urged to use was through a recipe published in the Oswego Free Press of June 30, 1832:

“Take half a gill of red lead and one gill of salt; next stir them half a minute; pour two-thirds of a wine glass of sulphuric acid; let the cork be loose, so that the air can escape, for one minute; then cork it tight; put it in cold water, and shake it under the water once a minute for fifteen minutes; let it settle. The liquid is of a greenish color, and is fit for use.”

It was reported in the Oswego Palladium on August 1, 1832 that 14 people had died in Buffalo.

Apparently an alarm prohibiting public events was lifted by midsummer, as at the meeting of August 15 it was resolved "that permission be given to W.B. Baucker and his company of Equestrians to perform their usual circus feature in East Oswego for a term of seven days."

Cholera in Kingston

A similar situation had occurred on the north side of Lake Ontario at Kingston, ON, when The Kingston Chronicle and Gazette reported on June 23, 1832:

“Rules for Cholera Outbreak at Kingston – no vessel allowed to enter harbour until inspected by Health Officer; a fine of 40 shillings for any Master of a Vessel bringing sick or dead person into harbour; and carter to lose license if he refuses to take a sick person to the hospital.”

One of the major losses in Canada was Captain James McKenzie, skipper of Canada’s first steamboat on Lake Ontario, the Frontenac. The Upper Canada Herald of August 29, 1832 reported:

“It will be perceived that Captain James McKenzie of the Royal Navy, a gentleman universally known and respected in Upper Canada, died of Cholera on Monday last. He was attacked with the disease in its most violent form on Sunday, and altho' efficient medical aid was promptly procured, every exertion for his recovery proved fruitless. He was a man of an intelligent mind, and being at sea in the merchant service from his early youth, his abilities as a seaman were of that order which, on joining the Royal Navy, soon raised him to the first class of officers of his rank.”

“He came to Canada with the first division of the Royal Navy, sent from England to serve on the Lakes during the late war. While the flotilla were making ready at Kingston in the spring of 1813, he, in the arduous duty of boat service, quickly made himself acquainted with the best channels and anchoring ground on the American, as well as on this side of Lake Ontario, so as to be enabled to conduct the squadron to various places between Kingston and Sacket's Harbour, to the entire satisfaction of his Commander-in-Chief.”

“At the conclusion of that war, he returned to England, and was placed upon half-pay; but his active habits led him to consider and study the powers of the steam engine, and he soon made himself acquainted with its complicated machinery. In the year 1816, he returned to Kingston, and assisted in fitting up the “Frontenac,” the first steamboat used on the waters of Upper Canada, which he commanded till she was worn out – since he has commanded the “Alciope” on this Lake, and at the time of his death was engaged in the construction of two other steamboats, one at the Head of the Lake, and one at Lake Simcoe; and he was on most occasions consulted respecting the construction and management of steamboats, so that he may be justly called the father of steam navigation in Upper Canada.”

References

Dictionary of Canadian Biography, entry for Captain James McKenzie; https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/mckenzie_james_1832_6E.html

Encyclopedia of Cleveland History

The Cholera Pandemic of 1832 in New York State;

https://www.newyorkalmanack.com/2020/05/cholera-pandemic-of-1832/

Robertson, John Ross; Landmarks of Toronto: a collection of historical sketches of the old town of York from 1792 until 1833; Publication date 1894

Various newspapers.

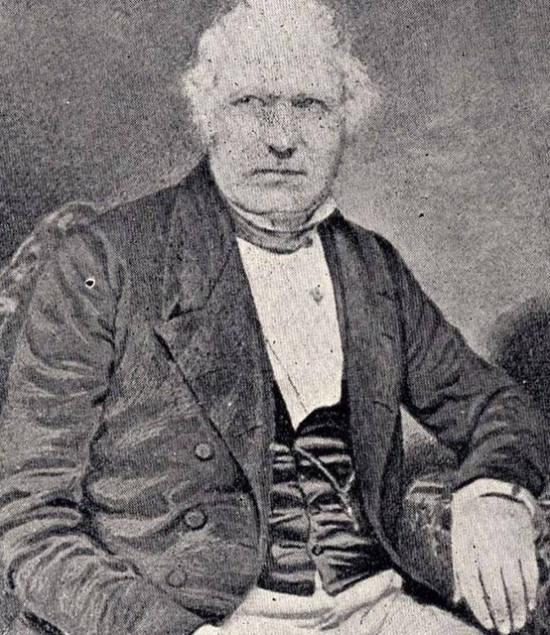

By Richard Palmer

Richard Palmer is a retired newspaper editor and reporter, and he was well known for his weekly historical columns for the “Oswego Palladium-Times,” called "On the Waterfront." His first article for TI Life was written in January 2015, and since then, he has dozens of articles and more. He is a voracious researcher, and TI Life readers certainly benefit from his interests.