“Beauty and Strength, the life and work of American sculptor Sally James Farnham.”

by: Sarah Ellen Smith

“Beauty and Strength, the life and work of American sculptor Sally James Farnham.”

While the world isolated and borders shut down, an exhibit opened at the Frederic Remington Art Museum in Ogdensburg, N.Y., which will surprise and delight art lovers and historians. Sally James Farnham, a leading artist of her time, finally has been given the attention she has long been due, as Ogdensburg’s “other famous sculptor.”

I went to the museum with a friend from art school days, to show her that there was more to Remington than just cowboys. Neither of us had heard of Sally James Farnham. By the time we walked through the exhibit, I realized that there was more to the Frederic Remington Art Museum than Remington himself. This is the largest public and permanent exhibit of Sally James Farnham’s work and it celebrates this forgotten woman’s life.

At the height of Sally James Farnham’s career, famous celebrities and politicians of the day sought her out for portraits. She had a yacht named after her. In addition, she was well paid and internationally known for her sculptures.

Yet now, she is little known, except for her monument to Simon Bolívar, in Central Park. It is a statue I remember marveling over in my twenties, not knowing that a fellow Northern New York woman had created it! Let alone that a self-trained artist won the commission and was paid $25,000 (about $700,000 in today’s money) for what was then the largest known equestrian statue made by a woman.

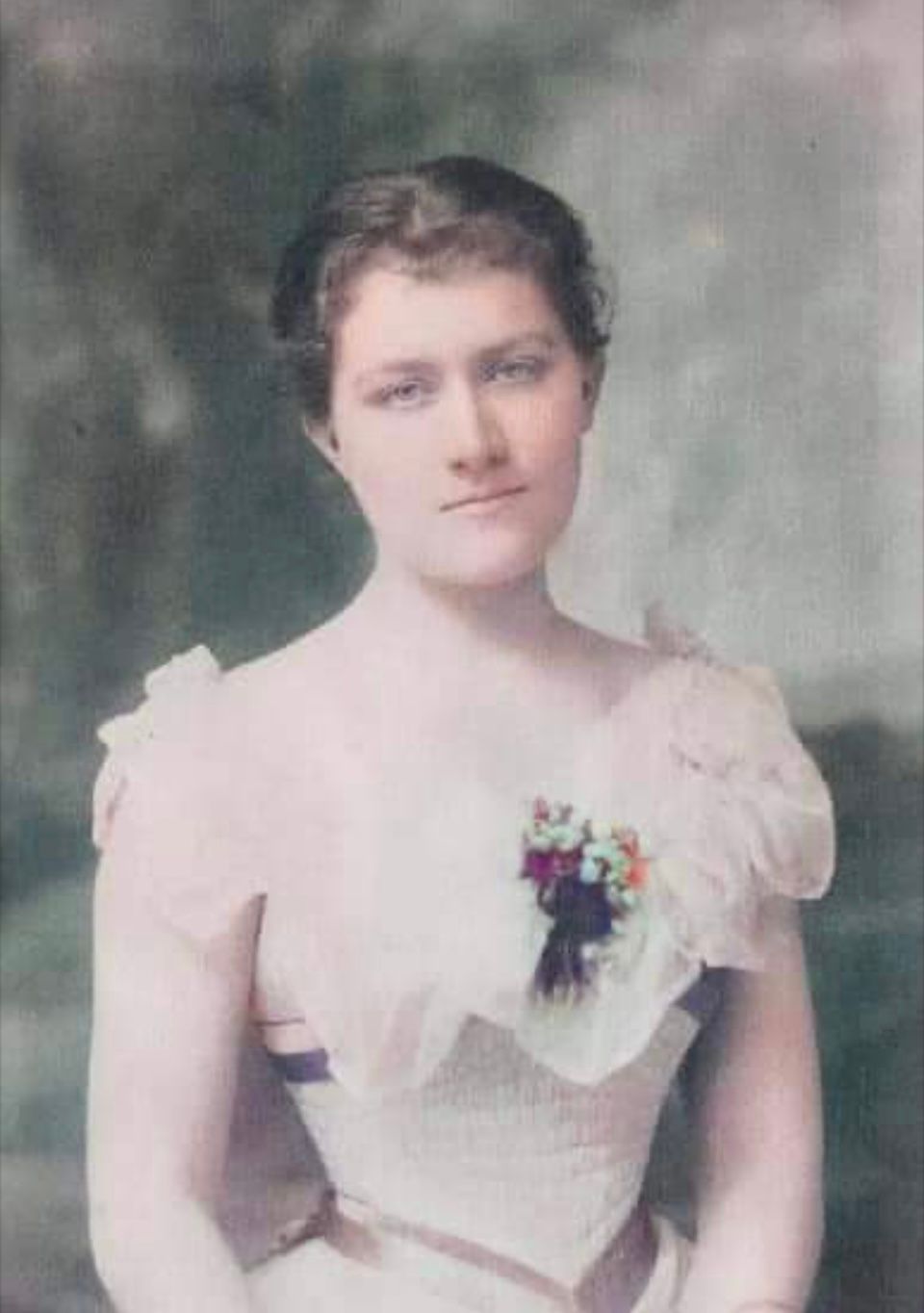

Born in Ogdensburg in 1869 to a prominent family, Sarah Welles James grew up in a privileged world, with horses, travel, and an appreciation of art. It wasn’t until 1901, after marriage and two children, that the 32 year old Sally discovered her inherent talent for sculpting. Northern New York native and family friend, Frederic Remington, recommended his foundry and soon she was casting her work in bronze. Without formal training, she threw herself into sculpting and fearlessly submitted designs for public monuments. Within five years, she had won commissions for large, well-paying pieces.

Sally James Farnham resided on Long Island and in New York City as an adult, but she continued to have strong ties to Ogdensburg. For the months of August or September, she and her family came to stay along the St Lawrence River, with her sister Lucia James Madill.

As a member of the Ogdensburg chapter of the DAR, Sally heard of plans for a memorial to be placed in a park over looking the St Lawrence River. She went up against 16 other submissions and won the job. She had only been sculpting for four years. In 1904, the Civil War Soldiers’ and Sailors’ memorial “Spirit of Liberty,” one of her first major sculptures, was erected in Ogdensburg.

A winged victory figure stands atop a soaring 35-foot column. At the base are four large eagles, above shield shaped plaques. Sally was always committed to accuracy and bought an eagle, later donated to a zoo, to be used as a model for the ones on the base of her “Spirit of Liberty.” Originally, a figure of a Union soldier stood guard at the base. Due to repeated vandalism, the soldier was later removed to the lobby of the Frederic Remington Art Museum. The monument was a tribute to Sally’s beloved father, Colonel Edward C. James, who had served in the Civil War as the colonel commanding the U.S. 106th Volunteer Infantry.

Years later, it was the Winged Victory that caught the imagination of yet another Ogdensburg native, Michael Reed, an undisputed Sally James Farnham expert. A florist by day and art historian by night, Reed spearheaded the Sally James Farnham Catalogue Raisonne Project, which catalogs all of her work. He also helped Sally join the digital age by maintaining a website and a Facebook page dedicated to her life and work. Reed is also the key researcher for this exhibit, a monograph on her life, and a nine-part webinar produced by the Frederic Remington Art Museum.

Michael Reed told me via an email conversation, “Growing up in Ogdensburg, my parents would bring me to play in the park across the street from the monument, and I always wanted to go gaze up at the face of Liberty, rather than play. While in college, I spent a summer as a guide at the museum. It was the same summer George McFarland’s article on Sally came out in the St. Lawrence County Historical Association’s Quarterly. I then knew who had designed ‘my monument.’ I soon realized she was a sculptor of great importance, but had fallen into obscurity over the years. She really took hold of my imagination, and I’ve dedicated my life to uncovering everything Sally.”

Michael Reed’s catalog of Farnham’s work is ever expanding, as he comes across previously unknown pieces. In 2021, he discovered bronze plaques in The Art Institute of Chicago, “languishing under an ‘unknown maker’ credit.” It was Reed who recognized, researched, and was able to get the Reverends Mather plaques properly attributed to Farnham. He told me that there was a trophy she designed for a regatta in Alex Bay, which has yet to be rediscovered. Another trophy she designed is in the Antique Boat Museum, in Clayton N.Y.

“It is difficult to decide which is the more fascinating, Mrs. Farnham the woman or Mrs. Farnham the artist.” This statement from an early art critic is quoted on a panel of the exhibit.

Sally had a conventional life as a society woman, married to Tiffany& Co. jewelry designer George Paulding Farnham, and mother of three. But in many ways, her life changed when she took up sculpting. She turned it into a career, at a time when most women could not have done so. Her social and economic situation in society secure, she was able to ride her horse everyday in Central Park, maintain studios in posh apartment buildings, own many pets, and had staff to help run the household.

When her husband lost his job and began a descent that drained the family’s funds, Sally divorced him. Somehow, she avoided the scandal of divorce and became the sole supporter of her family. She worked tirelessly and is quoted as saying,” This past year I have worn out three pairs of overalls in my studio work.”

Sally James Farnham’s first studio was on West 57th Street in New York City. She shared the building with many artists, writers, and intellectuals of the illustrious Algonquin Round Table. She was considered to be on the fringe of that group, but often did portraits or used them as models. Her energy and attitude translated into many friendships. This tradition continued in her second studio, in the famous Hotel des Artistes, with neighbors like Norman Rockwell and Rudolf Valentino.

The redheaded Sally was known to have ridden in a suffragist march and was an honorary member of NYC mounted police. Warring Harding, the first president for whom she might have voted, was said to have been pleased with her portrait of him. As was President Theodore Roosevelt, who was too busy to sit for her, so he invited her to sit in on a cabinet meeting.

She sculpted portraits of world leaders, actors, artists, dancers, historic scenes, and animals. In addition to monuments, medals, and trophies still in use today, she designed shoes for Macy’s, costumes for theater, and also stage design.

Her good friend, Frederic Remington, was her mentor and encouraged her early work. Later in her career, she was asked by Remington’s widow Eva to complete several projects left unfinished at his death. They shared a love of horses and some of Sally’s first and last pieces were homage to her friend and mentor. She gave several of her own pieces to the Remington Art Memorial when it opened in 1923.

Sally James Farnham died in 1943 at the age of 73. “A Merry Heart Goes All the Day,” is her epitaph.

One has to ask, how did this very successful artist fade from art history’s notice? I asked Laura Desmond, FRAM’s Curator and Educator, and her quick response was, “Well, Sally James Farnham was a woman. When the Simon Bolivar monument was dedicated (in 1911), a major newspaper failed to give her name as the artist. This is how it was.”

Michael Reed points out that artists like Sally, “Whose work was figurative, rounded in the late Beaux Arts representative tradition, began to see demand for her work diminish.” The work fell out of style, as more expressionistic and abstract works became the trend. Either way, Sally was lost to history, but thankfully, now has been found again, in this fascinating exhibit.

Years in the making, this exhibit was designed by Jakub Janiga with inspiration and instruction from Laura Desmond. Laura proudly showed me an interactive screen that answers questions, displays many photos, and provides details of ‘all things Sally James Farnham.’ The exhibit was generously funded by the Robert F. and Eleonora W. McCabe Foundation.

A note to visitors: Your ticket to the Frederic Remington Art Museum also includes an entry ticket to the Clayton Boat Museum. A great value, to visit two of the area’s attractions. Visitors shouldn’t miss taking a walk across the street, to the park in front of Ogdensburg Public Library, to see Sally James Farnham’s lovely Winged Victory in the Spirit of Liberty monument.

Author’s Note: I can not thank Michael Reed enough, for his quick and friendly responses to my many questions, and to Laura Desmond of FRAM, for her infectious cheer in the webinars and in our interview. I would also like to acknowledge the historic legwork of George McFarland and Peter H. Hassrick. Thanks also to Chris Wiewel and Janet Smith Staples.

By Sarah Ellen Smith

Sarah Ellen Smith began shooting photos, drawing, and painting what she saw along the shores of the St Lawrence River and Lake Ontario as a young artist. In the years since, she has traveled the world gathering images, observing art, and art makers. In 2010, Sarah Ellen returned to be a year-round River resident. After collaborating with John Arnot at St. Lawrence Pottery for over ten years, she is now working in her studio outside of Clayton and teaching at the Thousand Islands Arts Center.